Richard Neitzel Holzapfel

Utah History Encyclopedia, 1994

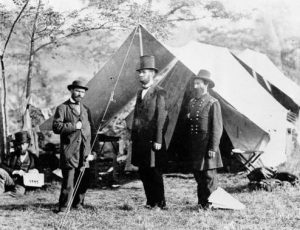

President Abraham Lincoln, Allen Pinkerton, and General McClellan at Antietam during the Civil War. Brady Photograph

Governor Alfred Cumming left Utah quietly on 17 May 1861. Officially, Cumming was on a leave of absence, but the citizens of Utah knew that his hasty departure meant that he did not intend to return. General Albert Sidney Johnston, another leading figure in the territory, also left the area during the same period. Both men’s actions were a result of events in South Carolina on 12 April 1861, when the Confederate Army attacked the federal garrison at Fort Sumter. This incident ignited one of the greatest tragedies in United States history, the American Civil War (1861-65). Both Cumming and Johnston were Southerners and chose to return to the South as the nation began to divide.

Many Mormons in Utah viewed the events in the east as fulfillment of statements made by their prophet/founder Joseph Smith nearly thirty years earlier: “Verily, thus saith the Lord concerning the wars that will shortly come to pass, beginning at the rebellion of South Carolina.” In a later statement made in 1843, Smith added: “The commencement of the difficulties which will cause much bloodshed previous to the coming of the Son of Man will be in South Carolina. It may probably arise through the slave question.”

Even while the Latter-day Saints believed that the dissolution of the Union vindicated their prophet’s statements, they also had profound regard for and belief in the divine nature of the U.S. Constitution. Such potentially conflicting emotions created a unique atmosphere in Utah.

Because some Saints construed Smith’s words to mean that the Second Coming of Christ was near at hand, they also had mixed emotions about the Civil War. In addition, they still were insecure in the aftermath of the Utah War. While they were interested in self-rule and state’s rights questions, it is apparent that the people in Utah never really seriously considered supporting the Confederacy. In fact, on numerous occasions they affirmed their loyalty to the Union. Although the majority were suspicious of Lincoln’s policies during the early days of his presidency, the Saints changed their attitude, especially after a reported favorable statement made by Lincoln about them gained general circulation in Utah.

President Abraham Lincoln, it was reported, said that when he was a boy there was a lot of timber to be cleared from his farm. Sometimes he came to a log that was “too hard to split, too wet to burn, and too heavy to move,” so he plowed around it. That, Lincoln contended, was exactly what he planned to do about the Mormons in Utah. “You go back and tell Brigham Young that if he will let me alone I will let him alone.”

The Saints did not send men to the battlefields in the east to fight in the war, nor were they invited to do so. Some Utahns did go, but on an individual basis. Brigham Young believed that the dissolution of the Union would possibly be the end of the nation. The war was also seen by many Mormons as divine retribution upon the nation that had allowed the Saints to be driven from their homes, unprotected from the mobs, on several occasions. Following the departure of Cumming and Johnston, the troops at Camp Floyd also left by July 1861. This allowed the Saints to demonstrate their loyalty to the Union. Members of the Nauvoo Legion, the local militia, performed short-term volunteer service guarding the mail line. Another significant act of loyalty occurred when Brigham Young was given the privilege of sending the first message from Salt Lake City on the newly completed transcontinental telegraph in October 1861. His message to Lincoln: “Utah has not seceded, but is firm for the Constitution and laws of our once happy country.”

In April 1862 President Lincoln asked Young to provide a full company of one hundred men to protect the stage and telegraph lines and overland mail routes in Green River County (now southern Wyoming).

In 1863 the people of Utah made their third attempt to achieve statehood. The Mormons chided their critics by reminding them that while many states were trying to leave the Union, Utah was trying to get in. This third petition was denied, however. In the meantime, a constitution was drafted for the proposed state of Deseret and a full slate of officers was elected with Brigham Young as governor. This “ghost” government of Deseret met for several years and, in many cases, made decisions that usually became law when the territorial legislature met officially.

To the surprise of the citizens of Utah, the local militia was eventually replaced by the Third California Volunteers, who had been ordered to take over the guard duty from the Saints. In October 1862 General Patrick Edward Connor arrived in Salt Lake City at the head of the 750 volunteer soldiers from California and Nevada.

It was apparent from the time Connor arrived that he believed earlier accusations of the disloyalty of Utahns. The Saints were mortified when his army did not occupy abandoned Camp Floyd. Instead, Connor chose a site which overlooked the city in the foothills directly east of Salt Lake City. This new military post was named Camp Douglas (later Fort Douglas).

In his position as military leader, Connor’s main assignment was to suppress Indian attacks against the overland telegraph and mail. A skirmish between the army and Indians occurred shortly after the troops’ arrival when three Indians were killed and one wounded on 24 November 1862.

The most significant clash between federal troops and Indians took place on 29 January 1863, in what has become known as the Battle of Bear River or the Massacre at Bear River. Connor’s force of 300 troops attacked a Shoshoni encampment on the Bear River and killed more than 250 men, women, and children. They also burned the village and thus broke the strength of the Indians in the area.

Connor also attempted to influence Utah’s economics and politics. He established the Union Vedette, an anti-Mormon paper, which became a vehicle to criticize the Saints. Another consequence of the U.S. Army’s presence in Utah, directly related to Connor’s intentions of curing the Latter-day Saints’ influence in Utah, was the opening of mining operations in the area. Connor hoped that this would attract more non-Mormons to the area and thus curtail Mormon hegemony.

Shortly after the beginning of the Civil War, Governor Stephen S. Harding replaced acting governor Frank Fuller. Harding, along with Connor, sought to mitigate Mormon influence in Utah affairs. The new governor accused the Saints of disloyalty. After he attempted to set aside the powers of local probate courts and the territorial militia, the Saints petitioned the president for Harding’s removal. Lincoln responded, in what can be seen as an act of reconciliation, by replacing Harding. The president, however, in an effort to placate non-Mormons, also replaced officials liked by the Saints, including Judge John F. Kinney and territorial secretary Frank Fuller.

Harding’s replacement, Governor James Duane Doty, gained the Saints’ support and cooperation by showing the genuine impartiality advocated by Lincoln. Utahns showed their respect for the President during the celebration of his second inauguration. Salt Lake City authorities and LDS church leaders organized a joint patriotic celebration on 4 March 1865.

News of Lincoln’s assassination caused a deep sense of loss among Utahns, and they joined in the national mourning. Businesses and the Salt Lake Theater were closed, flags were hung at half-mast, and many homes in the territory were decorated with emblems of mourning. Even Brigham Young’s personal carriage was draped in black crepe. Mormons and non-Mormons alike met in the Tabernacle, which had also been draped to eulogize the fallen president. A Mormon authority and the army chaplain from Camp Douglas spoke to those gathered.

Another sad event soon followed. Governor Doty, who was considered by Saints and non-Mormons alike as a judicious executive and perhaps the best the territory ever had, died in June 1865.

As the war was coming to an end and it was apparent that the Union would be victorious, Young still hoped that the crisis in the East would allow the Saints to achieve statehood, removal of the army from Utah, protection of the Saints’ rights, and election of local officials.

At the conclusion of the Civil War, General Connor was honorably mustered out of the volunteer army on 30 April 1865. In the immediate postwar years, he remained a leader of the anti-Mormon movement and became involved in Utah politics.

While Utah did not achieve statehood, the withdrawal of the army, or the ability to influence the appointment of federal officials, the LDS church generally thrived during the Civil War period. Converts still gathered and settlements continued to be established in the Great Basin. Brigham Young remained the respected leader of the Saints, and the church remained a viable, independent power. Utah Territory and its people, however, were inevitably less isolated. Compromise by both federal officials and church leaders during the Civil War helped to bring about a period of more peaceful coexistence in Utah.

See: E. B. Long, The Saints and The Union: Utah Territory during the Civil War (1981).