Thomas G. Alexander

Utah, The Right Place

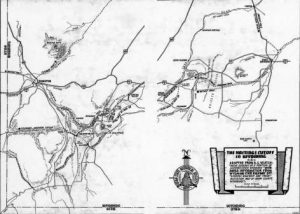

“The Hastings Cutoff in Wyoming, adapted from A.C. Veatch: ‘Aerial geology of a portion of southwestern Wyoming’ with added information from Wyoming State Highway Dpt. ‘General highway and transportation map of Uinta County, Wyoming.” Digital Image © 2009 Utah State Historical Society.

Anxious to attract Americans to northern California, Lansford W. Hastings published his famous Emigrants Guide to Oregon and California in 1845, which touted the Golden State over the Beaver State. At the same time, it is unclear whether Hastings intended to promote the cutoff from Fort Bridger through Salt Lake Valley and westward via the route Fremont followed in 1845 or simply to comment that a route would be more direct than the usual trail through Fort Hall.

At any rate, a number of people thought the Hastings Cutoff had good potential, though others opposed it. Lining up in favor of the cutoff stood Fremont, whom Hastings had consulted at Sutter’s Fort during the winter of 1845-1846, James Hudspeth, James Bridger, and Louis Vasquez. James Clyman, a partner of Hastings who accompanied him and several others from Sutter’s Fort to Fort Bridger in early 1846, tried to dissuade the members of the Donner-Reed party from taking the cutoff, and Joseph R. Walker, who had successfully guided the first wagons over the California Trail by way of Fort Hall, thought the route an unproven risk.

Early parties on the trail in 1846 followed the normal route north through Fort Hall and across northwestern Utah. By mid-July, however, members of four of the migrant parties feared they might not cross the Sierra Nevada before becoming snowbound and decided to take the Hastings Cutoff. On July 20, both the mule-back Bryant-Russell party, named for Louisville newspaper editor Edwin Bryant and party captain William H. Russell, and the party of wagoners led by George W. Harlan and Samuel C. Young left on the Hastings Cutoff. James M. Hudspeth guided the Bryant-Russell party, and Hastings himself guided the Harlan-Young group.

Lansford W. Hastings

Instead of going down Echo Canyon, the route that I-80 follows today, the Bryant-Russell party followed the Bear River to the present site of Evanston. They crossed over to the headwaters of Lost Creek, which they followed to its junction with the Weber River. Backtracking to East Canyon, they reached the Weber near Devil’s Gate. Passing Devil’s Gate with difficulty, they emerged into the Salt Lake Valley, and then struck south around the lake.

Leaving the same day as the Bryant-Russell party, the Harlan-Young wagons found Echo Canyon by a rather circuitous route. Hudspeth met them in Weber Canyon and directed them into Morgan Valley. Hastings tried to dissuade them from continuing down Weber Canyon through Devil’s Gate, but Hudspeth assured them they could drive through. Cutting a road only with abundant effort and losing at least one team and wagon to the narrow rocky canyon, they channeled through the lower Weber and on to the Salt Lake Valley.

In the meantime, Hastings had returned to start Heinrich Lienhard’s party of thrifty Germans on a more direct route to Echo Canyon. After reaching the Weber River, they followed the tracks of the Harlan-Young Party. By floating ox-tethered wagons over water-drenched boulders, they managed to pass Devil’s Gate and reach the mouth of the canyon. Having made up several days, they caught up with the Harlan-Young party near the Jordan River.

The fourth party, led by George and Jacob Donner and James Reed, did not leave Fort Bridger until July 31. They found a note near the present site of Henefer in which Hastings warned them not to use the Weber Canyon route, promising at the same time to show them a better road. On August 6, Reed hurried out from the party to catch Hastings west of the Oquirrh Mountains. Hastings took Reed to the summit of Big Mountain, where he described a route from Henefer through Emigration Canyon. Following this route, the Donner-Reed party lost more time and met with extreme hardship both there and in the Salt Lake Desert. Struggling into Nevada, they became snowbound near Donner Lake. Eventually only forty-seven of the original eighty-seven reached Sutter’s Fort.