Miriam B. Murphy

History Blazer, February 1996

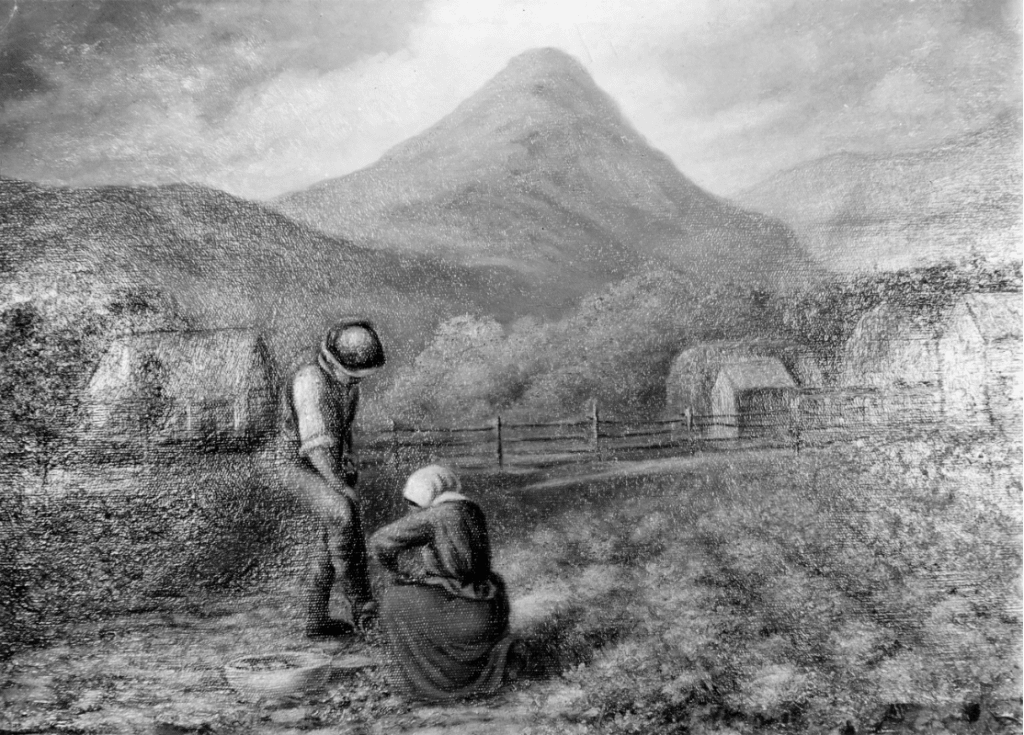

Drawing of farmers at Oakley, Utah. Artist unknown.

Although the first years of white settlement in Utah brought many hardships, including food shortages, by the late 1850s local farmers were producing a surplus of food. Unfortunately, historian LeRoy R. Hafen noted, the nearest settled areas—California, Oregon, and New Mexico—lay hundreds of miles away over deserts and mountains, making profitable trade unlikely. Then gold was discovered in the Pike’s Peak area in 1858–59, and thousands of eager prospectors virtually stampeded across the plains to the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains. The mining camps of Colorado (then called Jefferson Territory) became Utah’s nearest neighbors, but at that they were more than 500 miles away over precarious “roads.”

At first the Colorado miners and settlers received their supplies of food and goods by freight from Missouri or New Mexico. “During 1859,” Hafen wrote, “flour sold at $10.00 to $20.00 per hundred pounds in Denver, potatoes and onions at twenty-five cents per pound, butter at one dollar, eggs at seventy-five cents per dozen, and other produce in proportion.” When Utahns heard of the high prices being paid in Colorado, a few enterprising individuals began to make plans to serve the Colorado market.

So it was that during the summer of 1860 supply trains left Salt Lake City and Provo for Colorado via Fort Bridger, South Pass, the Sweetwater, and the North Platte to the little town of Denver—perhaps not yet deserving of its epithet “the Queen City of the Plains.” The local newspaper, the Rocky Mountain News, reported on October 5, 1860: “There arrived yesterday a vast quantity of fresh eggs, butter, a large quantity of onions, barley, oats, etc., only fifteen days from the city of the Saints.” Moreover, the report continued, 12,000 sacks of flour, 5,000 bushels of corn, and assorted other foodstuffs were en route from Utah. The newspaper was astonished to find trade coming from the west when Camp Floyd in the heart of Utah Territory was still being supplied from Missouri—“even the corn and oats that is fed to stock.” The newspaper drew its own conclusion: “The Mormons must be prospering, and Uncle Sam must be very shortsighted, or some of his agents are great rascals. We are assured that this flour that is coming is equal in quality to the best superfine from the states.”

On October 10 Mr. Crisman’s wagon train from Salt Lake City arrived in Denver, and the following day two trains of 26 wagons each of Miller, Russell & Co. from Provo showed up. Their cargo consisted primarily of flour and oats. Flour had been selling at $15.00 per hundred pounds, but the large shipments from Utah drove the price down to $8.00 per hundred.

Utahns continued to freight flour and other supplies to Colorado during 1861 and 1862. Prices fluctuated, but the trade was profitable enough to keep the wagon trains on the road. Hafen said that Lt. Caspar Collins, “stationed to guard the road along the upper North Platte from Indian attacks,” recorded the passage of Utah freighters headed for the Colorado mining camps with food in 1862.

The development of agriculture was slow in Colorado, and when the settlers did take it up they looked at Utah’s irrigation methods for their model. They were especially impressed with the success of Utah farmers in fruit growing. Brigham Young had sent grapes and peaches to Maj. Ed. Wynkoop in Denver, and he apparently shared them. A writer for the Commonwealth exclaimed: “The fruit was nice—we have never tasted finer. And why shouldn’t we have it in Colorado as well as in Salt Lake!”

In 1864 Utah peaches got another rave review when Father Raverdy, on an assignment in Utah for the Catholic church, sent a box of fresh peaches to Bishop Joseph P. Machebeuf in Denver. The stage line charged the prelate $60 for the express service. But, according to Machebeuf’s biographer, W. J. Howlett, the bishop “hit upon the idea of offering a number of peaches for sale at the seemingly extraordinary price of one dollar each. But peaches were an extraordinary fruit just then, and he had no difficulty in disposing of a sufficient number at that price to pay the cost of carriage and he had enough left for an abundant treat for himself and the Sisters and pupils of St. Mary’s Academy.”

See: LeRoy R. Hafen, “Utah Food Supplies Sold to the Pioneer Settlers of Colorado,” Utah Historical Quarterly 4 (April 1931).