Linda King Newell

History of Piute County

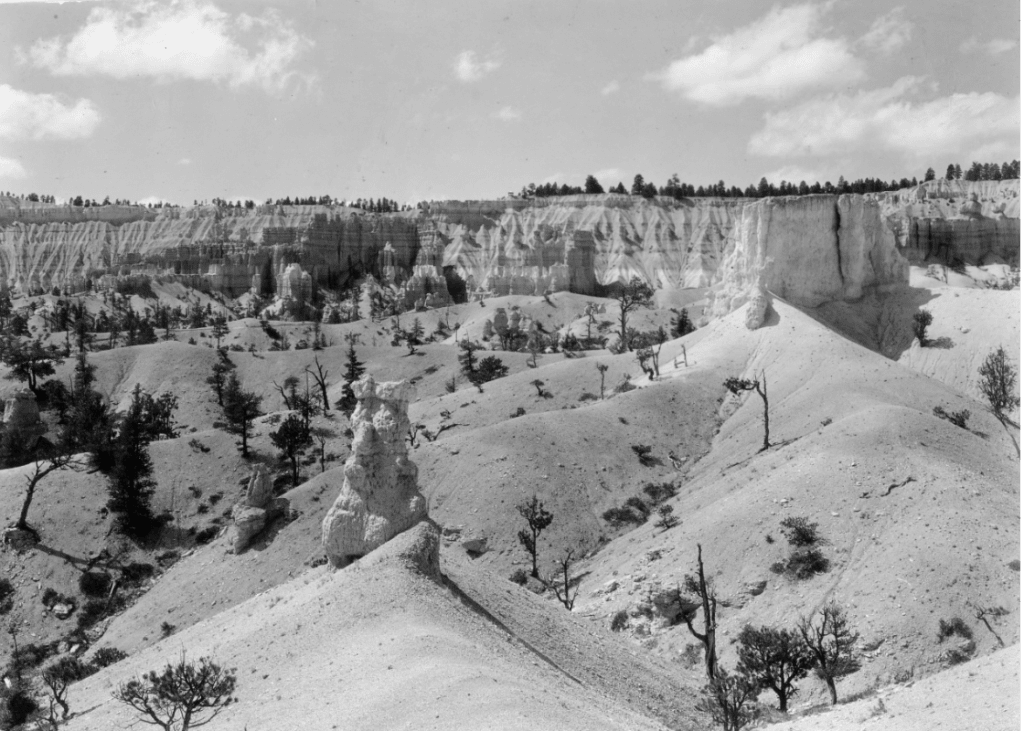

Fairyland Canyon

Even before World War I the automobile signaled the birth of a new industry—tourism. Residents of [Utah] had known the splendor of Bryce Canyon for decades, but the roads to the canyon were little more than wagon trails, and sight-seeing trips were not an option in the work-a-day world of most residents. But the arrival of the automobile and the transfer of forest supervisor W. H. Humphrey from Moab to Panguitch on 1 July 1915 helped catapult this scenic wonder to national attention. Elias Smith, forest ranger of the East Fork Division of the Fishlake National Forest invited Humphrey to go with him to see the canyon. Although “he was loath to take the time right then . . . the ranger insisted.”

Natural Bridge

“You can perhaps imagine my surprise at the indescribable beauty that greeted us,” Humphrey later wrote. “It was sundown before I could be dragged from the canyon view . . . I went back the next morning to see the canyon once more, and to plan in my mind how this attraction could be made accessible to the public.” Humphrey assigned the publicizing of Bryce Canyon to Mark Anderson, foreman of a Forest Service grazing crew. Anderson’s first view of the canyon came early the next spring. Immediately on returning to Panguitch he telegraphed a message to the district office in Ogden asking that regional forest service photographer George Goshen “be sent down to Bryce Canyon with movie and still cameras to take pictures of the grazing crew “at work near the plateau rim.” Goshen lost no time; he arrived by train in Marysvale the next day and took a car to Panguitch, arriving by evening, and worked all the following day. A stack of photographs and the movie were sent to U. S. Forest Service officials in Washington, D. C., and also made available to Union Pacific Railroad officials in Omaha, Nebraska.

The first two descriptive articles about Bryce Canyon came out in the latter part of 1916. One article was by a member of the grazing crew, Arthur W. Stevens, illustrated by Goshen’s photographs, for the Union Pacific publication Outdoor Life. The second was an article for the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad’s periodical Red Book, dictated by Humphrey and published under the name of clerk J. J. Drew. Since this railroad had a spur as far south as Marysvale, Humphrey tried to interest its owners in the tourism possibilities of Bryce, Zion, and Grand Canyons, with Marysvale as the jumping-off station. He may even have hoped the line would be extended to Panguitch. In the summer of 1917 the director of the Utah State Automobile Association, C. B. Hawley, drove to Bryce Canyon and came away impressed. As a result of Hawley’s visit and later excursions by other Automobile Association officials, Salt Lake Tribune photographer Oliver J. Grimes came to take pictures of the canyon the next summer. He published a full-page article entitled “Utah’s New Wonderland,” which appeared in the Tribune‘s Sunday magazine section on 25 August 1918. Grimes become state secretary to Governor Simon Bamberger, and, although he was unable to influence the governor to improve U. S. Highway 89 and make Bryce Canyon more accessible (Bamberger once said, “I will build no roads to rocks!”), Grimes did influence the Utah Legislature to pass a “Joint Memorial” on 13 March 1919, directed to the United States Congress. It asked Congress to “set aside for the use and enjoyment of the people a suitable area embracing ‘Bryce’s Canyon’ as a national monument under the name of the ‘Temple of the Gods National Monument.'”

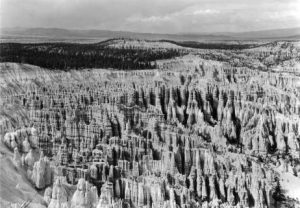

Silent City

Steven Mather, the first director of the National Park Service, urged new Utah governor Charles R. Mabey and the state legislature to make Bryce Canyon a state park rather than a national park. After three years, however, the state had failed to do anything and Mather agreed in 1924 to make the canyon a national monument, administered by the National Forest Service.

Until new roads could be built between Zion National Park and U. S. Highway 89, tourist traffic was routed primarily through Marysvale by way of the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railway. Three automobile touring companies met the train each day as it arrived at Marysvale. Arthur E. Hanks, a Marysvale resident, conducted one-and-a-half-day tours to Bryce Canyon and a four-and-a-half-day trip to the Grand Canyon’s North Rim by way of Bryce Canyon. Kanab resident H. I. Bowman had his headquarters in Kanab for a touring business that took in both Bryce Canyon and the North Rim. Only one company, Parry Brothers of Cedar City (owned by Chauncy and Gronway Parry) served all four area scenic destinations: Zion, Cedar Breaks, Bryce, and the North Rim. These tours, however, were not inexpensive for the 1920s. Parry Brothers charged eighty dollars per person for a five-day trip to the North Rim and Bryce; an eight-day grand loop tour of all four scenic locations cost $140.

In 1924 the Utah Parks Company subsidiary of Union Pacific Railroad got approval to establish an auto stage line from Cedar City through the scenic lands of southern Utah to Marysvale. It would radiate from both towns so that tourists arriving in Marysvale via the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad would also be served. The route would extend to Cedar Breaks, Panguitch Lake, Bryce Canyon, and Zion National Park. Parry Brothers, which had operated this service on a somewhat smaller scale, would thereafter serve only the route to the Grand Canyon. The Richfield Reaper reported that forty twelve-passenger touring cars were to be placed in service by the parks company, at a cost of $190,000. The Utah Parks Company was also investing $798,791 in facilities at the two parks, with $363,208 having already been allocated. The central lodge and cabins at Zion were nearly complete. Fifty-one cabins at Bryce would be finished by the opening of the tourist season that year. At Cedar Breaks the stages would have a lunch stop, and the company would build facilities there as well.

The D&RGW responded by again modifying its schedule to accommodate the tourists. Trains would arrive at Marysvale forty minutes earlier, at 4:30 P.M., and leave for a return trip the next morning eight minutes later, at 8:22. The company also installed new passenger coaches on the Marysvale line, making travel much more comfortable. The touring companies did well until 1930, when the National Park Service completed the Zion Tunnel, which enabled the Union Pacific Railroad to better utilize their Cedar City spur line and dominate the train and bus tour industry to Bryce Canyon. They contracted services from the Parry Brothers to take the rail passengers from the railhead in Cedar City to Zion National Park, the North Rim of the Grand Canyon, Bryce Canyon, and back through Cedar Breaks.

The D&RGW not only curtailed its passenger service but its mail service as well. The stock market crash of the previous October was probably partly responsible for this decision. Area residents again rallied and petitioned the railroad to reconsider. It did. On 1 June 1930 the first train to inaugurate the new mail service arrived in Marysvale to a celebration the likes of which had not been seen since the opening of the Marysvale spur in 1900. The new “fast train” arrived in Marysvale shortly after noon, in time to carry the mail on to Kanab the same day. The return train would leave at 12:45, arriving in Salt Lake City in time for mail to be distributed there the next day. Spectators lined the tracks at each stop to show their support for the new schedule. At Marysvale, D&RGW assistant traffic manager A. J. Cronin received a rousing welcome. Some 400 supporters from Gunnison to Panguitch were on hand at the station with a “pep” band. Three passenger cars on the train were also filled with shouting, singing boosters.

Marysvale mayor J. W. Robinson and a band greeted the passengers. Mayor F. G. Martines of Richfield served as master of ceremonies, thanking the railroad officials for their response to the area citizens. Cronin said that the railroad “would be laying rails south of Marysvale right now if it were not for the financial depression that hit the country last October when the stock market crash came.” According to the Richfield Reaper, “He believed it would only be a matter of a short time until this track will be extended down to Panguitch and eventually on to the Pacific Coast as originally planned.”