John S. McCormick

Beehive History 16

Ontario Mine workers with lunch pails and daily supply of candles prepare to descend the shaft of this famous Park City mine, ca. 1902.

The history of silver in Utah is a long and fascinating one. Some evidence exists that Spaniards and Mexicans, and perhaps Native Americans, engaged in mining at various locations throughout the state—including present-day Iron County, Utah Valley, Summit County near Kamas, and Minersville–before permanent white settlement began with the arrival of the Mormons in 1847. Almost from the first the Mormons mined on a small scale as part of their effort to develop a self-sufficient economy. Every community needed coal for heating, iron for tools, and lead for ammunition, but there was little interest in prospecting for precious metals.

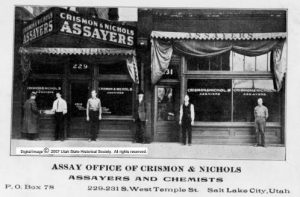

Assayers, such as these employed by Crismon Nichols, analyzed the mineral content of ores to determine their potential worth.

The lure of riches from the earth was not nearly as strong for Mormons as it was for many other people. Church leaders realized that a rush of non-Mormons into Utah would follow a successful discovery of precious metals. Such an influx would undermine the isolation and unity within the religious community that the Mormons sought. Moreover, in their view, a permanent society could not be built on mining. Mines became exhausted. People moved away. Ghost towns developed. The foundation of permanence and stability was agriculture. The comment of Mormon apostle Erastus Snow was typical: “It is better for us to live in peace and good order, and to raise wheat, corn, potatoes, and fruit,” he said, “than to suffer the evils of a mining life.”

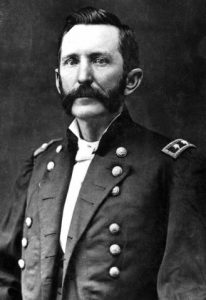

Colonel Connor’s Role

The development of the precious metals industry in Utah began in the early

Patrick Edward Connor

1860s with the arrival of Col. Patrick E. Connor, commander of the Third California Volunteers, who had been sent to Utah in 1862 to keep an eye on the overland mail routes during the Civil War. Connor, a staunch anti-Mormon, quickly set about to reduce church influence by exploring and developing the territory’s mineral wealth. If gold, silver, and other precious metals were found in Utah, he thought, the resulting flood of miners into the territory would overwhelm the Mormons, and gentiles would soon predominate. So he sent the men under his command out to prospect, and they almost singlehandedly opened the precious metals industry in Utah in 1863 by locating deposits, staking claims, and establishing mining districts.

Until it became possible to transport large quantities of ore to distant markets, however, mining could not really grow, and the industry did not become important until after the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 and the subsequent spread of a network of rails throughout the territory. After that, mining began to develop on a large scale. Rich mines flourished in the Wasatch Mountains east of Salt Lake City, in the Oquirrh Mountains west of the city, in Rush Valley, in the Tintic Mountains, and at many central and southern sites, including Frisco in Beaver County where the fabulous Horn Silver Mine was located, and at Silver Reef near St. George—an unusual place to find silver since it does not ordinarily occur in sandstone. In 1880 a visiting journalist described Utah as one large mining camp with Salt Lake City as its Main Street.

A Major Industry

By the turn of the century mining was a major industry in the state, second only to agriculture. According to the 1860 census only four miners earned a living in Utah, while in neighboring Colorado nearly 80 percent of the adult males were engaged in mining. A decade later 500 miners worked in Utah and by World War I about 10,000. The value of Utah’s mineral production increased from $190,000 in 1869 to $10 million in 1880 and to over $100 million by the middle of World War I.

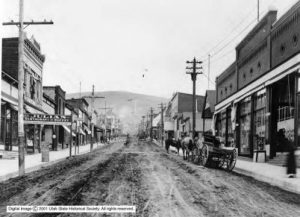

Park City, Utah, one of the West’s great mining towns, 1912.

Silver was the most important early metal and remained so until the early 20th century when copper eclipsed it. More than any other metal, silver was the foundation on which family fortunes, industrial employment, and development of mining areas were based. Until the turn of the century more than half of Utah’s mineral production was silver, which in turn totaled about 20 percent of the silver production in the United States. In 1925 Utah mines accounted for 32 percent of the nation’s silver. Since then the amount produced and the percentage of the nation’s production have both declined. Even so, Utah remains an important silver state. In 1983, the last year for which figures are available, it provided 10.5 percent of the silver produced in the United States, and the Hecla Mining Company’s Escalante Mine in Iron County is one of the top ten silver-producing mines in the country.

Given the Mormon preoccupation with building a stable society based on agriculture, the development of mining in Utah remained, for the most part, in non-Mormon hands, but there were exceptions. One of the best known mine owners was “Uncle” Jesse Knight, an active Mormon with extensive holdings in the Tintic Mining District. His company town, Knightsville, was probably the only saloon-free, brothel-free, mining town in the United States. Old-timers said that no man prayed more and met with more success than Knight. “He prayed for silver and gold in them thar hills, and there was silver and gold, and sure enough, he struck it,” one man said. In time, as the mining industry developed, more and more Mormons went to work in the mines. Still, non-Mormons predominated.

Immigrant Workers

Most of the workers were newcomers to the territory, many of them “new immigrants” from eastern and southern Europe and Asia. Throughout the 19th century Utah was a territory of immigrants. In 1880, for example, nearly one-third of the population was foreign born, most of them Mormon converts from the British Isles, Scandinavia, and western Europe. Toward the end of the century that began to change. New groups began to arrive. Part of a larger stream of 20 million people who reached the shores of the United States between 1880 and 1920, many came to Utah by chance rather than by design. Utah was where they happened to get a job, where they had a friend or relative, or where they decided to get off a freight train after a long and exhausting ride. For at least the first generation, they worked at pick and shovel jobs, mainly on the railroads and in the mines and smelters. By the early 20th century, for example, the population of Park City, which a generation earlier had been the home of a few Mormon farmers, included several dozen national groups, among them Chinese, Greeks, Italians, Slavs, and Serbs.

Silver mining added richness and diversity to Utah’s population. It also added a new element to the Utah landscape, the typical American mining town. Ramshackle colonies of shanties, saloons, gambling dens, dance halls, and brothels, all hastily thrown together at the first rumor of a strike, sprang up throughout the territory. Even those towns that evolved from frantic mining camps into more settled communities contrasted in appearance very much with the remarkably similar rural towns that historians have called “Mormon villages,” with their wide streets and large blocks laid out in a grid pattern, in which most Utahns lived in the 1860s.

“Nature’s Great Lottery”

The population of the mining communities, as one historian observed of Park City, was essentially divided into two groups, a small wealthy class and a large working class. Theoretically, silver society was upwardly mobile and the industrious could become wealthy. In fact, few did. “Mining is Nature’s great lottery scheme,” a contemporary observer said, and, as with any lottery, few of the participants held winning tickets. One person might be industrious and yet lose everything but his shirt after several months’ hard work, while another would make thousands of dollars in a few hours.

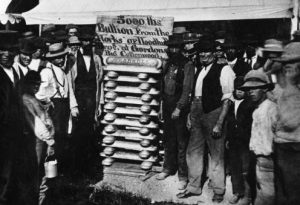

The Woodhull brothers made their first run of bullion in September 1870 at their Murray smelter, one of the earliest such facilities.

Of course, the age of the individual entrepreneurs did not last long. Individuals and partnerships with little backing made most of the initial discoveries, but by the late 1870s or so the easily accessible surface ores were exhausted. After that large corporations with substantial capital took over mining development, and most people involved in silver mining became wage workers who labored long hours for low pay at physically demanding and dangerous work.

There was nothing romantic about work in the mines, and it is a mistake to think there was. Miners received about $3.00 a day until well past the turn of the century and, as historian Dean May says, deserved more. Until 1896, when the first Utah State Legislature passed a law limiting work in the mines to eight hours a day, miners typically worked ten or twelve hours a day, six days a week. Accidents were common. Hoists were dangerous. So were falling rocks and runaway ore cars. Falls down mine shafts were one of the most common fatalities. The air was often so bad that candles the miners carried burned at only one-fifth of their normal intensity. Miners became ill and sometimes died from lead poisoning. Methane gas was another serious hazard. A frightening number of miners developed lung diseases.

Job insecurity also plagued miners. Few could count on full-time work the year around. The periodic recessions and depressions that affected both the American economy as a whole and the mining industry in particular resulted in long periods of unemployment and often wiped out the savings of even the most frugal families. And once out of work, miners were left adrift. Public relief was nonexistent and private charity insufficient.

Though most people in mining did not get rich, some did. Silver formed the basis of a few huge personal fortunes and spawned extensive financial empires. Park City, for example, the most important mining district in Utah in the 19th century, had produced twenty-three millionaires by the early 1890s. One of them, David Keith, came from Virginia City, Nevada, to supervise installation of a 500-ton Cornish pump with a working capacity of four million gallons a day to remove water from the Ontario Mine.

Thomas Kearns with daughter and son, Helen and Edmund, and, seated, wife Jennie Judge and son Tom, outside their South Temple home, now the Governor’s Mansion.

Thomas Kearns also built his fortune in Park City. Legend has it that he arrived in town in the late 1880s with only a pack on his back and a dime in his pocket. A decade later he was a multimillionaire, owner with Keith of the Salt Lake Tribune, and a U.S. senator.

A third Park City millionaire was Susanna Bransford Emery Holmes Delitch Engalitcheff, Utah’s famed and flamboyant “Silver Queen,” whose worldwide travels and lavish entertainments outlasted her four marriages and $100 million fortune. More than anyone she represented the quick fortunes and luxury living that silver sometimes produced in Utah.

In addition to giving birth to a new economic and social elite, silver altered Utah’s landscape. It built or helped to build mansions, skyscrapers, luxurious hotels, and exclusive clubs. Many of the mansions on Salt Lake City’s East South Temple, known as Brigham Street until the early 20th century, were built with silver money. A number of them have been demolished over the years, but some remain, including those of David Keith and Thomas Kearns, the latter now the Governor’s

Utah’s Silver Queen Susanna Bransford Emery Holmes Delitch Engalitcheff

Mansion. Silver also built St. Ann’s Orphanage, now a school; Judge Memorial High School, which was originally a miner’s hospital that Mary Judge intended as a tribute to her husband, John Judge, who died of lung disease at the age of forty-two after long years of working in the mines; and a number of skyscrapers and commercial buildings, including Salt Lake’s McIntyre Building, McCornick Block, Kearns Building, Keith Building, Judge Building, and the public library building that now houses the Hansen Planetarium.

More Silver Buildings

Silver paid for the buildings that comprise the Exchange Place Historic District at the south end of Main Street near Fourth South, all of which were built around 1910 by non-Mormon mining men, in particular Samuel Newhouse, in an effort to construct a gentile commercial district at the south end of the central business district to counterbalance the concentration of Mormon establishments at the north end of the city. Silver helped finance the Alta Club, too, as a symbol of gentile prosperity. Founded in 1883, its original eighty-one members were mainly non-Mormon mining magnates. Mormons were initially excluded from membership, a reflection of the extreme division that existed between Mormons and non-Mormons in 19th-century Utah. After the turn of the century, however, Mormons were gradually admitted to the club–but no women until 1987–and for the next several decades it served as an important instrument of accommodation between Utah’s Mormon and non-Mormon communities.

Boston and Newhouse buildings under construction, June 30, 1903, on Exchange Place.

Though Utah has been an important silver mining state, it has not been a significant manufacturing one. The state’s mining and smelting industries produced an abundance of silver, but only a few artisans created silver objects–handcrafted or mass produced–for use and display. The Navajos of southeastern Utah are an obvious exception. Silvermaking has always been important among them and represents a significant aspect of the history of silver in Utah. Within the state’s larger population, however, the production of silver articles has been a limited and small-scale activity. Silver items have been as conspicuous in Utah as in other parts of the country, but for the most part they have been produced elsewhere, either on the East Coast or in California, and then sold in Utah through local dealers.

UTAH SILVER PRODUCTION–Selected Years

|

A versatile material, silver can be fashioned into a variety of objects. In Utah, silver objects, whether locally produced or not, were used in the same diverse ways that they were elsewhere—for luxury goods and commonplace items, for everyday activities and for special occasions, both religious and secular. And, as elsewhere, silver in Utah was associated with, and provided a way of displaying, wealth and status. More than any other metal except gold, silver symbolized affluence and position.

Silver had an enormous impact on Utah’s history. It contributed to the diversification of the population, added new elements to the landscape, and helped build new fortunes and solidify old ones. It also stimulated the growth of railroads and related industries and contributed significantly to the rise of the labor movement. Before 1869 Utah was a closely woven fabric with only a few broken threads. It was a relatively self-sufficient, relatively egalitarian, relatively homogeneous society where the hand of the Mormon church was ever present and ever active. After 1869 it began to move in a different direction. As Dale Morgan says, the Kingdom of God began to be transformed into another among the kingdoms of the world. A social revolution began, and silver was one of its driving forces.

End notes:

Dr. McCormick teaches history at Salt Lake Community College. This article was extracted from a museum exhibit catalog with the same title that he authored in 1988.