Jeffrey D. Nichols

History Blazer, June 1995

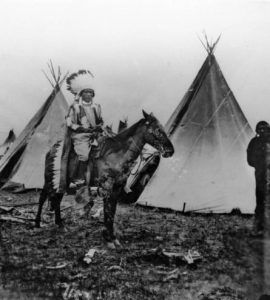

Ute dwellings

The May 26, 1906, Vernal Express spread the alarm: “Many of the residents of Uintah county may not be aware of the fact, but it is nevertheless true, that Indian trouble of gigantic proportion is brewing . . . .” A band of White River Utes from the Uintah and Ouray Reservation, numbering between 300 and 700, was on the move north. The Express continued: “They informed the settlers that they are going to one of the northern reservations where a great gathering of all the Indians in the west has been arranged for, to council over their supposed grievances. They express freely their determination to fight rather than return.”

Over the next several months the Vernal newspaper reported on the Indians’ progress until they arrived at a Sioux reservation near Fort Meade, South Dakota. Dispatches reprinted from Wyoming newspapers indicated that white residents feared potential Indian atrocities and depredations. Agent Hall of the Fort Duchesne Indian Agency was traveling with the Utes, trying to convince them to return to Utah, while federal troops were sent to escort them to South Dakota.

The Utes’ odyssey had deep historical roots. The traditional territory of the Ute-speaking peoples had encompassed a vast area, from Colorado’s Front Range to the Great Salt Lake Desert and from northern Colorado to northern New Mexico. Historically, the Utes had traded peacefully with Spaniards, Mexicans, and isolated traders, but the pressure of large-scale white settlement in the mid-19th century soon constricted their independence and led to conflict. President Abraham Lincoln established the entire Uinta Basin as a Ute reservation in 1861. Most of the Uintah band of Utes from central Utah had been forced onto the reservation by 1864. When the White River Utes (Yampas) of Colorado rose up and killed Indian Agent Nathan Meeker and several others, they were moved onto the Uintah Reservation in 1881, along with the unoffending Uncompahgre band of Colorado Utes.

The White River Utes refused to adjust to their new surroundings, sometimes returning to Colorado to hunt, which white settlers there called “poaching.” Uintah agency officials complained that the White River Utes laughed at the Uintahs for farming, calling it “women’s work.” White Americans generally expected and desired Indians to settle down, abandon their traditional hunting culture, and become farmers like themselves. When the natives resisted, whites ridiculed them: “He [Red Cap] had a good farm up the river from Myton, but he didn’t like it . . . If it had been groaning under its burden of ripening grain and fruit and if the fat cattle had been roaming over broad and luxuriant pastures he would have felt the same way. He and work didn’t agree.”

When coal, oil, and gilsonite were discovered or suspected on Ute land, whites pressured the government to open the reservation to exploration and settlement. The Dawes Severalty Act of 1887 established the principle of alloting individual tracts of land to Indians while opening the remainder to possible sale or commercial exploitation. White settlers began encroaching on Ute land in the 1880s and 1890s; in 1905 Indians began receiving allotments, and the reservation was opened to white settlement.

The Utes bitterly protested, arguing that the reservation could not be opened without their permission and that they had received poor land allotments. Red Cap and other White River leaders decided to seek the help of the Sioux, who had expressed friendship for the Utes in decades past. In 1906 Red Cap and his followers were apparently seeking an alliance with the Sioux or hoped that they could settle on the Sioux reservation.

The Utes quickly discovered that the Sioux, suffering their own hardships, could not or would not help them. The Sioux were surprised and dismayed at the Ute influx and would not even let them pasture their ponies free. The federal government, anxious to avoid war but determined to control the Utes, arranged employment for the tribe. Officials complained that the Utes refused to accept jobs on the Santa Fe Railroad, arguing that it would mean abandoning their ponies. In January 1908 the discouraged Utes wrote to Fort Duchesne, asking to return to the Uintah Reservation. The government supplied wagons, horses, and mules, and by October most had returned. The Vernal Express summarized the episode in the colorful, but racist, language typical of the era’s journalism: “We had pictured a fusillade of shot mingled with the wild war-whoop of the desperate redskin at bay as the gallant blueshirted cavalryman beats in the noble redman’s crust with the butt of a six-shooter as the windup of the sullen hegira of renegade Utes from the Uintah reservation. . . . The Ute simply snuffed some cocaine, dreamed he was on the happy hunting ground and crawled through a hole in the fence. He did not know where he was going, but he was on his way . . . a man with shoulder-straps rode up to them and said, ‘Hey, youse wanter git back where youse come from. Fresh beef and heap baccy.’ The red man grunted joyously. He had gotten the very plunder for which he was stalling. . . .”

The returning Utes attempted to make the best of their situation. The tribe eventually gained some recompense for their losses, a $32 million settlement in the United States Indian Court of Claims in the 1950s.

Meanwhile, whites were convinced that they had transformed the “worthless” former Uintah Reservation lands: “The only energy needed for a spectacular transformation was the white man with his brawny muscle and strong heart, and he came as has been his wont since civilization first diffused its glorious light in the east. He came and in one hand he carried the olive branch and in the other, peace. But the red man would have none of it . . . But despite that and all other obstacles the white man has succeeded. He has brought light out of chaos. He has made two blades of grass grow where only one grew before.”

See Vernal Express, May 1906-October 1908; Floyd A. O’Neil, “The Reluctant Suzerainty: The Uintah and Ouray Reservation,” Utah Historical Quarterly 39 (1971); Floyd A. O’Neil, “An Anguished Odyssey: The Flight of the Utes, 1906-1908,” Utah Historical Quarterly 36 (1968).