By Steven D. Branting

Rare are the individuals whose footprints remain in whatever places they call home during their lifetimes. It is one thing to live somewhere and quite another to leave a legacy there. One such person was Frederic Horatio Simmons, whose eventful life in territorial Idaho and Utah deserves to be remembered.

Born in Little Compton, Rhode Island, on December 22, 1830, Simmons grew up hearing the stories his grandfather told him about his Revolutionary War exploits. Ichabod Simmons joined the Continental Army at age fifteen, fought at Lexington and Bunker Hill, and was a member of General George Washington’s “Life Guard,” serving until 1783.

Frederic graduated from Harvard University Medical College with the class of 1853 and immediately came west to Jamestown, California, where he opened a pharmacy. Later that year he was initiated into the Masonic St. James Lodge No. 54. In August 1854, Simmons purchased a drug store in nearby Sonora, “nearly opposite his office.” He had clearly set upon playing a not uncommon dual role in the community—physician and druggist. Both would serve him well. One would bring him grief.

In January 1855, he was called to serve on a coroner’s jury in the bludgeoning murder of Joseph Heslep, the deputy treasurer of Tuolumne County. The townspeople of Sonora took the confessed killer from the jail, built a bonfire, and waited for the coming dawn, at which time they hanged him from a nearby oak tree. Simmons’ complicity in the summary frontier justice remains unknown. Lynch mobs are always populated with the “unidentified.”

By 1860, Simmons was on the move, this time to Portland, Oregon, where he transferred into Masonic Harmony Lodge No. 12. Portland’s cultural climate was a far cry from Jamestown, more attune to his Rhode Island heritage and Massachusetts residency. His next recorded place of residence was no stranger to vigilante groups, bawdiness, and brash opportunism—Lewiston, in the Washington Territory.

Early Lewiston was far from a safe place, frequented as it was by the likes of Henry Plummer, whose gang is said to have included every scoundrel between Lewiston and Virginia City, Montana. Local entrepreneur and founder of Idaho’s first Jewish community, Robert Grostein reported a murder the first night he spent in town, whose Lewiston Protective Association was said to number more than twenty-five men “kept continually on duty.” As many as 250 residents—many of them from the town’s wealthiest families—belonged to the organization at one time or another.

Simmons arrived in Lewiston before the summer of 1862, as his name appears among the advertisements in the first issue of The Golden Age on August 2, 1862. He listed himself as doing business on Third Street as a “dealer in drugs and medicine,” not as a physician. Fellow Lewiston practitioner Madison A. Kelly, M.D., a graduate of Jefferson Medical College (now Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia), long advertised himself as a druggist.

On November 8, 1862, members of the Association overpowered the guards at the city’s jail on First Street and took Dave English, Bill Peoples and Charley Scott “into custody.” They had robbed the Berry brothers at gunpoint as the men carried supplies to Lewiston from the gold fields at Florence, Idaho. The three culprits were found dead the next morning, “hanging by the neck” in a nearby barn. The jail was not more than one hundred feet from Simmons’s storefront, the barn even closer.

Simmons further consolidated his civic position on December 23, 1862, when he joined eleven other townsmen to form Idaho’s first Masonic Lodge after Thomas M. Reed, the Grand Lodge of Washington’s Grand Master, granted a dispensation. In his November 23, 1863, address reporting the Lodge’s activities, Reed commented that “these brethren have erected a new and commodious hall and have gone to work with a true and earnest zeal, evidencing much prosperity and usefulness.” Simmons was the Lewiston lodge’s first Junior Warden.

When the Washington Territorial Legislature incorporated Lewiston on January 15, 1863, Dr. Simmons was appointed to the first Common Council (now called the City Council), with Dr. Kelly as mayor.[1] Under the terms of its incorporation, Lewiston had the authority “to establish hospitals and make regulations for the governance of the same, and to secure the general health of the inhabitants.”[2] The Nez Perces County (Nez Perce today) commissioners quickly passed a levy to support a hospital.

The February 5, 1863, issue of The Golden Age carried a notice that “Dr. Orendorf, physician, surgeon and accourheaur [sic],” had offices at Simmons’ drug store. An accoucheur is a male midwife. Also a charter member of Lewiston Masonic Lodge, Frederick H. Orendorf was an 1835 graduate of Hanover College in Indiana. He gave up his practice in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, in April 1849 to follow the gold rush in California. He came to Lewiston from his practice in Oroville.[3]

The town took on a new identity on March 4, 1863, when the Idaho Territory was created by President Abraham Lincoln’s signature. A new territorial governor, William H. Wallace, a personal friend of Lincoln, would arrive in July. The Protective Association leaders claimed that the group had rid Lewiston of 200 thieves and gamblers by the spring of 1863, when the executive committee met for the last time and disbanded, just weeks before the arrival of Wallace, who undoubtedly would have insisted on the group’s dissolution.

Simmons threw himself into the workings of the territory’s fledgling Republican Party. Within weeks after William Wallace arrived in Lewiston, Simmons joined the bulk of Lewiston’s business and professional community to call for a convention of the party, which was held on September 28 at Mount Idaho, a thriving stagecoach depot located nearly eighty rugged miles southeast of the city. Wallace was elected as the territory’s congressional delegate. The dominant Democratic Party was completely out-maneuvered.

When the Nez Perce County Board of Commissioners met on October 20, 1863, to reorganize under the laws of the new territory, they selected Dr. Simmons as county treasurer. The same day, “the Union men of Lewiston” gathered at the Oriental Hotel on First Street to nominate candidates for the upcoming territorial legislative session in Lewiston, which had been named as the territorial capital. The sobriquet “Union men” bespoke the turmoil of the time. The Idaho Territory was rife with Confederate sentiment. Indeed, when the editor of The Golden Age raised the American flag atop the new pole outside his office, residents found the banner filled with bullet holes the next morning after Confederate sympathizers had given it a “twenty-one-gun salute.” The towns of Atlanta, Grayback Gulch, Dixie, and Stanley got their names from Confederate history. Robert E. Lee Campground can be found forty miles east of Boise.

“Dr. Simmons” was elected chairman of the “Union men.” It was the first reference to Simmons as a Lewiston physician. He would soon observe firsthand a political struggle whose ramifications are debated to this very day.

On 7 December 1863, eighteen delegates from what are now Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming met in a schoolhouse a block east of Simmons’s store to create the laws and regulations of the new Idaho Territory. No issue posed more difficulty than the placement of the capital. The delegates from Montana and Wyoming complained about the distances involved. The south Idaho delegation began lobbying vigorously to move the seat of government to Boise City. Only a filibuster prevented the bill from passage. Records reveal that on May 6, 1864, Dr. Simmons received a payment of $30.00 from the territorial coffers “for [two months’] rent of room for committee of legislative assembly.”[4]

On November 14, 1864, the legislature convened a second time, this time packed with delegates from newly-created counties in the south. A political melee was unavoidable. In the meantime, the November 19, 1864, issue of the The Golden Age carried this notice: “Hospital. Next door to the drug store of F. H. Simmons.”

The Legislature passed Bill 15 to make Boise City the new territorial capital. Governor Caleb Lyon signed the bill and promptly left town, ostensibly to go duck hunting. Lewiston delegates obtained an injunction based on the fact that the Legislature had acted outside its prescribed calendar. A standoff ensued.

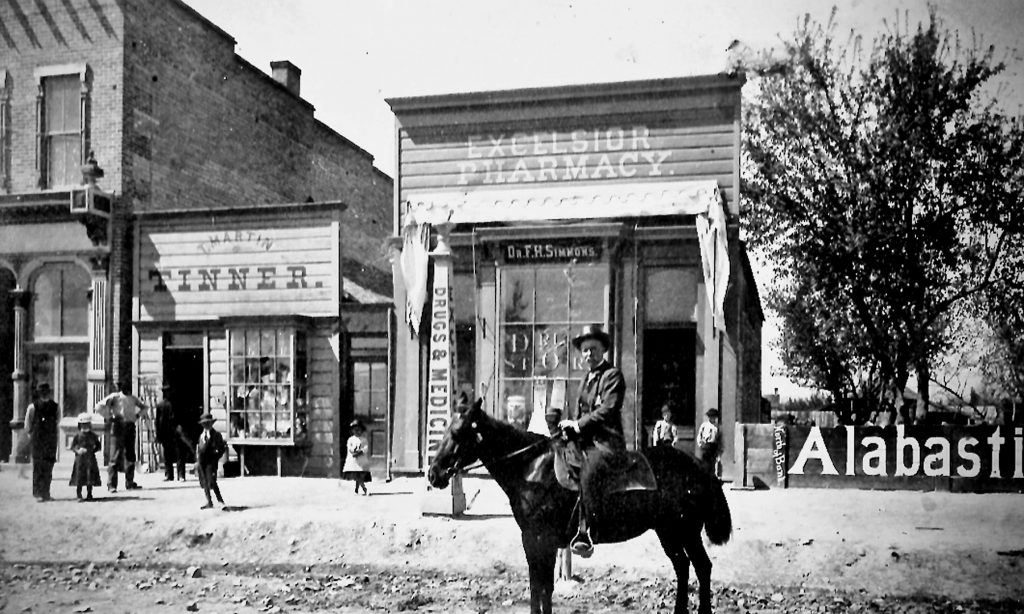

The January 28, 1865, issue of the North-Idaho Radiator printed two separate notices regarding Dr. Simmons: “Nez Perce County and Private Hospital ̶ F. H. Simmons, Proprietor” and “Dr. F. H. Simmons, Physician and Surgeon. D Street, between First and Second.”

The question as to whether Orendorf or Simmons organized the hospital will never be adequately answered, but the decades of experience that Orendorf brought with him lends weight to him as being the driving force for the hospital before the Idaho Territory was created in March 1863. A collaborative effort would have been to both of their benefits. Regardless of who should credited, the hospital was in the line of fire for one of the most important dates in Idaho’s history, a day that unfolded right before Dr. Simmons’ eyes.

At 10:00 a.m. on March 30, 1865, word reached Lewiston that Territorial Secretary Clinton Dewitt Smith and a detachment of federal troops from nearby Fort Lapwai were headed for the town to take custody of the territorial seal and other official documents. Rumors spread that the detachment would burn the community. Town leaders attempted to calm the crowds that gathered.

When members of Company F, First Oregon Cavalry, arrived at the city, some troopers took control of the Clearwater River ferry, while others, ignoring the presence of the deputy marshal Joseph K. Vincent, broke the lock to a cell in the city jail and gathered up the territorial seal and accompanying documentation, which townspeople had conveniently amassed for what they thought to be safekeeping. The papers-of-state in hand, Smith and his escort crossed the Snake River by ferry into the Washington Territory and, therefore, out of the jurisdiction of Lewiston’s law enforcement officials. A town in an uproar is a disorganized community ripe for disintegration. An 1866 Idaho Supreme Court decision upheld the Legislature.

Lewiston’s Masonic Lodge surrendered its charter in July 1865, based on the fact that “a quorum of the lodge could not be obtained, the members being scattered through the mining districts.” The town underwent unforeseen changes. By 1867, two independent reports state that only eleven white families still remained. The 1870 federal census verified that the community was now forty-percent Chinese. The Masonic Lodge would reorganize in 1874, but Dr. Simmons had already moved on.

After a short-lived residence in Helena, Montana, Dr. Simmons settled in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1870, before relocating to Provo in 1872, his arrival being well-documented in the Masonic records.

Masonry came to Utah with the U.S. Army. The first lodge opened at Camp Floyd (near present-day Fairfield) in 1858. As there was no Grand Lodge of Utah, subsequent lodges were, as was the case for Lewiston, formed under dispensations granted from surrounding states and territories, including even Montana in the case of early lodges in Utah.

Utah members changed that situation beginning January 16, 1872, when a four-day convention in Salt Lake City took up the question of forming the Grand Lodge of Utah. The week after the close of the convention, a petition for dispensation was drawn up and signed by nine men, one of which was Dr. Simmons, who was selected as the lodge’s “tyler,” the guard who examines the credentials of individuals wishing to enter the lodge. What would become Provo’s Story Lodge No. 4 was the first to be created under the auspices of the Grand Lodge of Utah. Eventually, in 1887, Dr. Simmons would rise to Worshipful Master of Story Lodge No. 4.

In 1874, at the age of 43, Simmons married nineteen-year-old Clarissa Speed. Two years later, soon after the birth of their daughter Celia Angeline, he and Clarissa moved to Alta, some forty miles north of Provo, where he opened a pharmacy and would serve as justice of the peace. The marriage soured, and the couple divorced in 1878. He would remarry in 1879 and gain a step-family.

In the late nineteenth century, Alta was the most dangerous place in Utah, whose newspapers carried headlines like “Unhappy Alta,” “The Awful Avalanche,” “Terrible tragedy,” “Latest Alta horror,” “Alta is swept away,” “More snowslides — Six persons killed at Alta,” “Terrible snow-slide in Cottonwood.” and “Another horror” with tragic regularity. The Simmons family would experience one of the worst events.

On January 15, 1883, Frederic and his new wife Samantha lost their eighteen-month-old son, Frederic Jr. Tragedy touched the family again in March 1884, when a massive snowstorm overloaded the weak snow pack in the hills around the town. At 10:00 p.m. on the seventh, an avalanche swept over Alta. “Last night was one of the most eventful known in the history of Alta,” Simmons wrote in a letter to colleagues in Salt Lake City. “We are used to severe and blinding snowstorms, to snow-slides and season of peril and danger, but last night was truly a night of horror.” Fifteen people would die, including fourteen-year-old John Richardson, Simmon’s stepson.

Soon after the Alta tragedy, Dr. Simmons moved his wife Samantha, his infant daughter Claudia and his step-daughter Ada Richardson back to Provo, where he would later serve on the city council from 1892-1895, be a founder and director of the Chamber of Commerce, and become the vice-president of the National Bank of Commerce. His drug store flourished and by early 1885 had “one of the finest stocks of drugs in the city.”

Winston Churchill once observed: “A lie gets halfway around the world before the truth has a chance to get its pants on.” Simmons was no stranger to having his name associated with sensationalized accounts in local newspapers. In June 1885, “a well-known and highly respected lady of this city” was said to have attempted suicide using laudanum. The woman’s reputation was about to be ruined until Simmons publicly debunked the scandalous misstatements. Yes, the woman was addicted to laudanum. Vast numbers of Victorian women were so afflicted, but the affair was an accident, not an intent.

A bizarre story from the summer of 1889 gave Dr. Simmons no little discomfort, being as it would have, if not corrected, fostered suspicions that he was careless and reckless with his diagnoses and protocols. The story started simple enough. On June 23, 48-year-old Ellen Gillard, a resident of Provo Bench, known now as Orem, died from the effects of an abnormal accumulation of fluid in the body, what people used to call “dropsy.” No physician attended her passing. The next day, friends and family members prepared the body for burial and held a viewing and short memorial service in the family home. In the afternoon, the mourners brought her body to the Provo City Cemetery, where sexton John Giles supervised the lowering of her remains into the ground.

All was returning to some sense of normality until July 16, when the Salt Lake Herald printed a story under the headline “A Horror At Provo.” The Herald alleged that some of the people who attended Mrs. Gillard’s viewing and memorial service noticed beads of what appeared to be perspiration on her brow. Other recalled that Ellen had an entirely different expression on her face at the cemetery than what they remembered when she was taken from the home. Her husband Henry recalled that his wife’s sister narrowly escaped being buried alive after she fell into a protracted trance.

Now at full steam, the Herald went on to relate that within an hour after the coffin was sealed, the friends and family had scurried to Dr. Simmons office and pressed their case. From what he was told, he suspected that the woman had been buried alive and would urge Giles to exhume her as quickly as possible. Nearly four hours after the burial, what must have seemed like a ghoulish mob confronted Giles, who was sill leaning on his shovel after just finishing up the closing of the grave. He agreed to their request and labored to open the grave and bring the coffin to the surface.

At this point in the account, the Herald could not contain its lurid imagery: “The sight that met the eyes of those about, struck them dumb with terror and remorse. The body had turned over in the coffin; the clothes were ripped to pieces and the disheveled hair gave every indication of having been savagely torn in the mad despair of the poor woman.”

The truth was that Ellen was dead. The Herald admitted it was impossible at that time “to get all the details of the terrible affair,” but defended itself, claiming that the information came “from such a good source that it cannot be doubted. Further particulars will doubtless be forthcoming from day to day.” Simmons seemed the hero, but the legend did not last long enough to be remembered as the truth.

Provo’s Utah Enquirer and the Deseret News both responded the next day with articles discrediting the Herald‘s “Horror” story. The Enquirer called the tale “a dime novel sensation,” and the News labeled the article “an ugly rumor.” Reporters from both papers had located Giles and learned from him what really happened on 24 June. Giles explained to the reporters that when he opened the coffin, her body was in the same position as when the coffin was closed. Giles also testified that the body had progressive discoloration and that her cheeks and neck had turned “a purple hue.” The Deseret News concluded that “there is no truth whatever in the story of her having been alive when buried.” The Enquirer agreed gleefully at the Herald’s expense.

The next day, the newspaper recanted the whole affair, all the while trying to save face. “The Herald‘s information on the subject came from a trustworthy source, and if our informant has been misled, it was through no fault of his.”

After several years of quiet success, Dr. Simmons’ name again appeared in the local press. In December 1899, Dr. Simmons, by then the city quarantine physician, was arrested and charged with manslaughter after he allegedly had filled a prescription negligently for gin with carbolic acid at the Elkhorn Drug Store in Provo.[5] The charges were complicated by the fact that he was a licensed physician but not a registered pharmacist. His defense attorney made the most of the testimony that the man who bought the bottle of liquid was not the person who drank it. Simmons did not take the allegations well. A reporter observed that “the aged doctor is very much agitated over the matter and became somewhat dramatic when he declared his innocence of a criminal offense. ‘I will never go to the penitentiary: there is more than one way of stopping this before it goes that far. It will never go to district court, for I will be dead before that.’”

Some feared he would commit suicide. “I will not kill myself,” he told court officials, “but it will kill me.” In April 1900, Simmons was acquitted on the charge of mislabeling the bottle but still faced a charge of deliberately substituting the acid. The label was found on the floor by a young man hired to tidy up the store after closing. It had been removed, folded and crumpled, tossed aside obviously after being properly affixed. Witnesses came forward to say that the deceased man had imbibed only a small portion of the bottle’s contents before collapsing. Combined with testimonies from the first trial, Dr. Simmons was clearly innocent, and the case was dropped by the acting district attorney on June 11.

Again, life only briefly returned to normal.

By 1903, his health had begun to decline rapidly. His life ended sadly in “senile disability” on December 15, 1905. He was buried with all the obsequies of the Masonic Lodge. By then Lewiston had a modern brick-and-mortar hospital with trained sister-nurses from the order of St. Joseph and a thriving medical community. The hardscrabble days of the frontier were gone. As American social reformer Daniel Carter Beard would lament in 1914 in the Fourth Annual Boy Scouts of America Report: “The hardships and privations of pioneer life which did so much to develop sterling manhood are now but a legend in history.”

Towns have a funny way of remembering their pioneers. Some names become parks and streets for reasons no one can remember. Others barely survive as words on the pages of old out-of-print books. The vast majority of our predecessors have faded completely from the collective consciousness. Dr. Frederic Horatio Simmons does not deserve that fate.

Citations & Sources

Daily Alta California, 21 January 1855

Deseret Evening News, 21 December 1899

__________, 19 December 1905

The Golden Age, 8 January 1863

__________,5 February 1863

__________, 24 October 1863

__________, 12 March 1864

Illustrated History of North Idaho, page 150

Alexis Kelner. (1980) Skiing in Utah: A History. See Sean Zimmerman-Wall, “Taming the White Tiger,” Utah Adventure Journal, 11 December 2009

William H. Knight. (1863) Hand-book Almanac of the Pacific States. San Francisco: H. H. Bancroft & Company, page 346

Lewiston Morning Tribune, 15 September 1929

_________, 5 May 1940

Masonic Record of Frederic Horatio Simmons, Story Lodge No. 4

Napa County Reporter,26 September 1868

North-Idaho Radiator,18 March 1865

Oakland Tribune,20 June 1891

Proceedings of the Grand Lodge of the Territory of Washington. (1863) Olympia, Washington: T. F. McElroy, page 261

Provo City and Utah County Directory. (1901) Salt Lake City: R. L. Polk & Company, page 11

Salt Lake Herald, 5 February 1885

__________, 16 June 1885

__________, 3 November 1886

__________, 19 December 1899

__________, 22 December 1899

__________, 21 January 1900

__________, 28 April 1900

__________, 17 December 1905

Salt Lake Tribune, 12 June 1900

Territorial Enquirer (Provo, Utah), 23 April 1886

Union Democrat (Sonora, California), 5 August 1854

Wood River Times, 13 March 1884

[1] See Article VIII, Section 1.

[2] See Article 1, Section 2; Article V, Section 2, Paragraph 4.

[3] By late 1864, Orendorf could be found in Idaho City, Idaho. From there he relocated to Helena, Montana, Territory. He then returned to California to set up his practice in San Francisco and later Oakland. He sold his practice there in June 1891 and moved his family to Los Angeles.

[4] Using an algorithm to calculate real price (the funds necessary for the upkeep of a family with food, clothing and shelter), the amount equates to about $510.00 today.

[5] Carbolic acid was a frequent device in cases of suicide and murder. See Steven Branting. (2015) Wicked Lewiston: A Sinful Century. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, pages 95-97, 147-156.