Richard A. Firmage

History of Grand County

Arches National Park, early 1930s to mid-40s

Aside from the hoped-for oil gusher or other major economic stimulus, there was one thing that farsighted boosters began to promote as a growth industry [in 1930]—tourism. The area’s scenic attractions were unparalleled, and in the decades just past they had begun to be more appreciated by Grand County residents and others in the world outside the county’s boundaries. The economic potential of the fact that the Windows area northwest of Moab had just been officially designated Arches National Monument was not lost on community leaders, and moves were already being made both to attract visitors to the area and to increase the size of the monument. Moab’s newly formed Lion’s Club was instrumental in both efforts. The club was organized in July 1930 and aggressively campaigned to bring increased tourism to the region while it lobbied for an enlargement of the new attraction and better access to the area.

The Times-Independent was already a force in those efforts. The newspaper had periodically mentioned the scenic attractions of the region in years past, but there is the suspicion that sometimes these articles also served as convenient “filler” material for the overworked editor. Many in the area were inclined to ignore its natural beauty and unusual scenic wonders in their concern to wrest a livelihood from the land. It is reported that when local rancher Marvin Turnbow led Michigan geologist Lawrence Gould to the Windows area of Arches, his response to Gould’s enthusiasm was, “I didn’t know there was anything unusual about it.” In a sense, the rancher was right: in a region of surpassing wonder, that area was not too unusual; yet, as Jos?nighton has exclaimed, “Only a stunted soul could be so dulled to glory.” Loren Taylor had a greater appreciation of some of the area’s natural wonders. On 9 March 1917, long before it was given its current name, Delicate Arch was featured on the front page of the local newspaper, where it was called a “gigantic window” and headlined as a “Scenic Wonder Near Moab.”

Delicate Arch

The prime mover in the establishment of Arches as a national preserve was Alexander Ringhoffer, an immigrant who was born in Hungary in 1869. He came to the United States as a young man and moved to southeastern Utah about the year 1917 to try his luck at mining and prospecting. He traveled throughout the region and was especially impressed by the beauty of the Klondike Bluffs area of what is now Arches National Park when he first saw it in late 1922. He called the area Devil’s Garden and was so enthusiastic about it that he was able to convince D&RGW railroad officials to look the area over. Tourism was big business to the nation’s railroad companies, and they were on the lookout for areas near their routes that they could promote in the hope of attracting tourists to travel to the locale. One railroad officer, Frank Wadleigh, was also impressed—so much so that he wrote to National Park Service (NPS) director Stephen Mather to suggest that it be made a national monument.

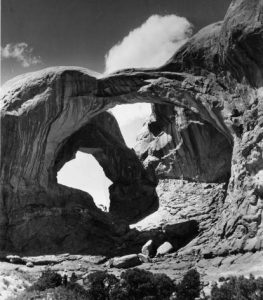

Double Arch

A survey was made for the Park Service from 12 to 14 July 1924; but the surveyor was misdirected by Heber Christensen of Moab, and so the survey was made of what is now known as the Windows area instead of the Klondike Bluffs area. Wadleigh saw the report in the Times-Independent of 17 July 1924 and noticed the discrepancy. He wrote Mather, and a new survey was conducted in June 1925.

Doctor J. W. Williams had often traveled on horseback through the Arches country to avoid difficult Hell Canyon on his rounds north of Moab, and he came to love the area passionately. After his retirement in 1919, he more actively began to promote the region. Dr. Lawrence Gould, a geologist from the University of Michigan, came to southeastern Utah in 1921 to study the La Sal Mountains. He was introduced by Williams to the Arches area and returned in 1924. That winter he wrote to Utah senator Reed Smoot urging that the Windows area be made a national monument. Smoot, in turn, began to pressure Stephen Mather of the Park Service, which had already conducted its preliminary investigation.

Although in 1924 the Moab newspaper had proclaimed upon the strength of the survey that the area was to become a national monument, and despite the fact that the creation of the monument had the support of NPS officials, D&RGW officials, Smoot, Gould, and others, the political climate in Washington for such a move was not favorable. The Secretary of the Interior, Herbert Work, had expressed opposition to more national monuments and was even considering downsizing or eliminating some that were already in existence. Park Service officials countered by going to the New York Times Magazine, trying to drum up public support, which began to materialize when a feature article on Arches was published on 9 May 1926.

When Herbert Hoover was elected president in 1928, the new Secretary of the Interior, Ray L. Wilbur, was favorably disposed toward Arches. President Hoover signed an executive order on 12 April 1929 creating Arches National Monument. The new monument consisted of two separate sections—the Windows and Devils Garden—yet comprised only 4,520 acres. Ironically, Klondike Bluffs, which had so inspired Ringhoffer, was not included in the monument at the time of its creation. The Devil’s Garden name he used for the Klondike Bluffs area was applied to the area so named in the present park. Frank Pinkley, superintendent of the Southwestern National Monuments division, gave the name for the monument. Pinkley was appointed first superintendent of the monument, serving until his death in 1940.

An official expedition was sent to Arches in 1933–34 to prepare a map of the area from a more accurate survey and to also conduct an archaeological investigation of the new monument. The expedition’s leader was Frank Beckwith, a newspaper editor from Delta, Utah. Beckwith was a good choice for the task. His group of about fifteen trained scientists and assistants completed their work by the end of March 1934 at a cost of less than $10,000. They named many of the landforms—including Landscape Arch and Delicate Arch (which previously had had a variety of names, including the Schoolmarm’s Bloomers and the Chaps)—and discovered dinosaur bones near Wolfe Ranch (a homestead established in 1898 by Civil War veteran John Wesley Wolfe and his son Fred which was sold by the Wolfe family in 1910). Beckwith published an official report and also wrote several articles publicizing the area. Maps and a geologic survey were also published as a result of the expedition. J. Marvin Turnbow, who bought the 150-acre Wolfe Ranch (not then a part of the national monument), was a member of the expedition and was named first custodian of the monument.

Though the monument had been created, much to the delight of it supporters, there was opposition to the general movement to withdraw lands from potential private entry and use. Grand County had its share of such opponents who resented the creation of the monument and who, in the years that followed, opposed attempts to enlarge it and to reclassify it as a national park (for example, such an attempt was reported in the 29 May 1934 issue of the Times-Independent). With the support provided by Taylor and his newspaper, boosters of an enlarged monument had a powerful ally.

Much of Arches National Park is located on a partially collapsed salt anticline called Salt Valley, approximately two miles wide and eighteen miles long. Though it was only a few miles from Moab, access to the monument in its first years was difficult and was generally from the northwest, crossing Courthouse Wash, or from the north along Salt Valley or Courthouse Wash. Improving roads to and within the monument was one of the primary goals of Taylor and other park boosters who reasoned that the attraction needed to be easily accessible to large numbers of tourists. In May 1931 a gravel road was completed with federal assistance between Moab and Grand Junction, Colorado. Highway 6/50 was built in 1934, providing a reliable east-west route near the railroad line in the northern part of the county. The Moab–Thompson road, present-day federal Highway 191 (formerly Highway 160), was first paved in the late 1930s, greatly facilitating access to the monument and to Moab itself.

The first recorded automobile trip to the new monument was by Harry Goulding, who drove to the Windows area on 15 June 1936. Others followed, but many were intimidated by the difficulty. In September 1937 Harry Reed, the monument’s custodian, reported a decline in visitation, which he attributed to the poor quality of the area roads. His successor, Henry G. Schmidt, endeavored to repair roads in the monument, but floods regularly caused damage, particularly where the entrance road from the west crossed Courthouse Wash. The main entrance route to the monument, used until 1958, left Highway 191 along Willow Springs Road, traveled to Balanced Rock, and then continued into the Windows area.

Plans periodically were made to improve access to the area; however, with the country in the midst of the Depression, money was tight. During the 1930s the government focused its attention on more limited projects within the monument. Still, the decade would have to be considered a most successful one by supporters of the monument, who were rewarded on 25 November 1938 for their efforts to promote the area. On that day, President Franklin D. Roosevelt enlarged the monument from 4,520 acres to 33,680 acres—a tremendous gain that included Courthouse Towers and Delicate Arch, which were made part of Beckwith’s survey at the urging of J. W. Williams. The enlargement received surprisingly little negative commentary in the local paper, as most area residents came to favor the idea after the Times-Independent publicized the area with a series of articles by Beckwith and others. Advocates of unbridled free enterprise and no government interference were in a definite minority at the time in the county as in the country. The president wrote Dr. Williams on 15 December 1938 thanking him for his support and ardent campaigning on behalf of the enlarged monument.