Jeffrey D. Nichols

History Blazer, June 1995

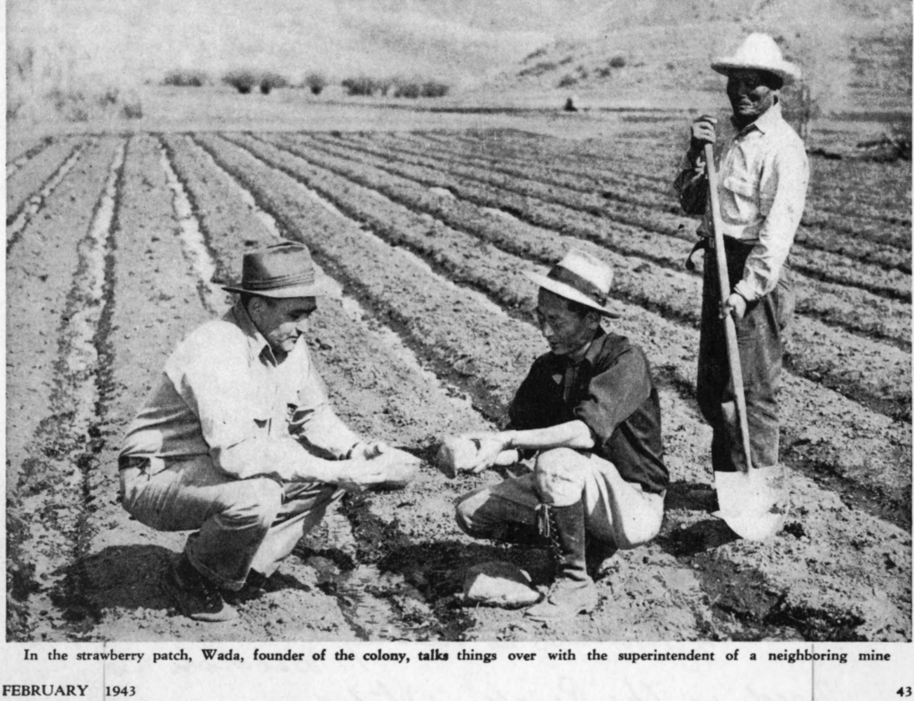

Fred Wada 1943

The story of the Japanese internment camps during World War II at Topaz, Millard County, and elsewhere is generally well known. A lesser-known story is that of Keetley Farms, an agricultural colony of “voluntarily” relocated Japanese Americans situated roughly halfway between Park City and Heber City.

The move to Keetley took place against a background of widespread anti-Japanese sentiment after the Pearl Harbor attack of December 7, 1941. Thousands of Americans of Japanese ancestry found themselves the object of suspicion and hatred. The immediate concern of other Americans was the possibility of sabotage, but California especially had a long history of prejudice against Japanese immigrants. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order No. 9066 authorizing the removal of 110,000 Japanese, U.S. citizens and aliens, from the West Coast to the interior in February 1942. The military authorities in California, headed by Lt. Gen. J. L. DeWitt, did not initially have the resources to move the Japanese, so for a brief time DeWitt encouraged voluntary relocation. Although some 10,000 Japanese indicated their desire to move voluntarily, less than 5,000 were able to do so; the rest could not leave their homes so quickly. Many encountered hostility during their exodus from the coast and had no chance of employment at the end of their journey.

A prosperous Oakland produce dealer named Fred Isamu Wada, whose wife Masako was from Ogden, decided to visit Utah to investigate possible areas for relocation for himself and other California Japanese. Duchesne County authorities attempted to attract the Japanese as agricultural laborers, but Wada decided that eastern Utah was too remote. Instead, he struck a bargain with Keetley mayor George Fisher, leasing land from him in exchange for a promise to bring Japanese to the area as farm labor.

Local reaction to the move was initially hostile. Although Utah residents were not as overtly anti-Japanese as Californians, few wanted Japanese living among them. The Park City newspaper, the Park Record, noted that the attacks on Hawaii and the Philippines had been meticulously planned, and that “all these dress rehearsals were supplemented by the most vicious and long-ranged fifth column activities that this war has yet seen.” Fisher allayed local suspicions in an interview published in the Park Record three weeks later by swearing to the newcomers’ loyalty and noting that the move had not cost Americans anything: “All evacuees brought to Utah by Mr. Fisher are American citizens, some of them second generation. According to Mr. Fisher, they came to Utah with no expense to state or federal governments, paying all travel expenses and freight charges on farm machinery themselves.”

On March 26 Wada and a number of other families left Oakland for Utah. (Wada, incidentally, would lose all of his property in California). They left just in time; on March 30 General DeWitt “froze” the movement of all persons of Japanese ancestry in preparation for their forced relocation. Those coming to Keetley would, at any rate, have at least a greater measure of freedom than the internees. Wada established from the start that the community would be a cooperative, nonprofit venture, growing food for the American war effort.

When the snow melted on the Keetley property the new farmers were disappointed at the poor quality of the land. “Hell,” Fred Wada later told an interviewer, “we had to move 50 tons of rocks to clear 150 acres to farm.” Still, they went to work, repairing buildings, planting a large truck garden, and raising chickens, pigs, and goats. Eventually, the Keetley farmers would herd beef cattle and raise dairy cows as well. Once the farm was established, maintaining it was left to wives and children while many of the men worked as laborers in sugar beet fields and on surrounding farms.

Local hostility toward the Japanese manifested itself early in two incidents of dynamite throwing, fortunately with no injuries. Wada met with representatives of local trade unions in April 1942 to assure them that the Japanese were loyal American citizens and to tell them, “We are here to produce foodstuffs for victory.” Relations quickly improved; many of the Japanese children attended school, either at Park City or Heber City, and the Keetley colonists adopted some American activities, including baseball. Several of them had relatives serving in the U.S. Army. The Keetley residents maintained close ties to the internees at Topaz; they made frequent visits there, and some internees furloughed to perform agricultural work came through Keetley.

At the war’s end, about two-thirds of the Keetley residents returned to their homes in California after the last harvest. The others remained in Utah, scattering to a number of different communities. Fred Isamu Wada moved his family to the Los Angeles area where he prospered in the produce business for many years. As for Keetley, its destiny was to be covered by the rising waters of the Central Utah Project’s Jordanelle Dam a half-century later.

See: Park Record and Wasatch Wave (Heber City) March/April 1942; Sandra C. Taylor, “Japanese Americans and Keetley Farms: Utah’s Relocation Colony,” Utah Historical Quarterly 54 (fall 1986); Marilyn Curtis White, “Keetley, Utah: The Birth and Death of a Small Town,” Utah Historical Quarterly 62 (summer 1994).