A History of Utah’s American Indians, © 2000

“The Navajos of Utah,” pp. 264–314

Nancy C. Maryboy and David Begay

Introduction

Navajos have been living in the Four Corners region of the American Southwest for hundreds of years. The land of the Navajo includes areas of southeastern Utah, northeastern Arizona, and northwestern New Mexico. Navajo people traditionally and historically refer to themselves as the Dine meaning the People. Other variations in the meaning of “Dine” also exist–for example, Child of the Holy People. Nevertheless, all the variations of meaning are an integral part of one whole, which expresses an interrelationship with the cosmos. Sacred oral stories passed down from generation to generation tell of cosmological origins and continuous evolvement through four eras or worlds, ultimately leading to what the Navajos call Hajiinei the Emergence, that brought the Navajos to their present location.

Navajos always have believed that their homeland is geographically and spiritually located within the area bounded by four major sacred mountains. Today Navajo land, held in trust by the United States government, has been set aside by treaty and executive order as an Indian reservation; however, this reservation is significantly smaller than the land that was culturally placed within the area of the four sacred mountains.

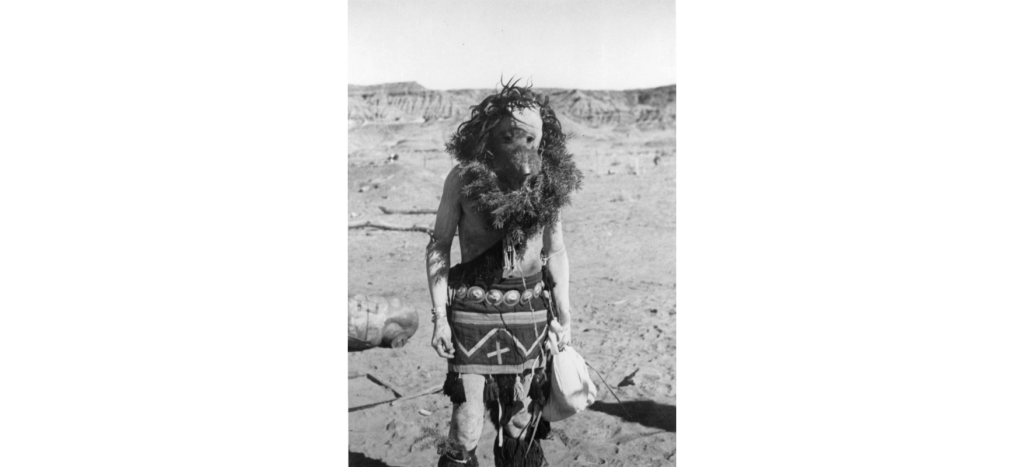

A Navajo man in ceremonial mask and costume, date and location unknown

The Navajo Reservation today extends over 25,000 square miles and includes parts of nine counties. It is the largest Indian reservation in the United States, being larger than the states of Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island, combined. According to the 1990 census, there were 219,198 Navajos in the United States, with the overwhelming majority living on the Navajo Reservation.

The four sacred mountains are located in three states: Sisnaajini–the east mountain (Mt. Blanca, located in south-central Colorado), Tsoodzil–the south mountain (Mt. Taylor, located in northwestern New Mexico), Dook’o’oosliid–the west mountain (San Francisco Peaks, located in northwestern Arizona) and Dibe Ntsaa–the north mountain (Mt. Hesperus, located in southwestern Colorado). There are two additional mountains of great signficance located in New Mexico–Chooli’i (Gobernador Knob) and Dzil Na Ood il ii (Huerfano Peak). Navajos in Utah also acknowledge the cultural significance of several other mountains, including Naatsisaan (Navajo Mountain), DzilDiloi (Abajo Peaks), and Shash Jaa (Bear’s Ears).

The following brief history of the Navajos of Utah attempts to present the perspective of the Navajo people themselves. This history differs from most standard textbooks in that it draws on oral history as told by Navajo elders as well as providing a reexamination of written materials from a native perspective. Both general American and Navajo history largely have been written from the point-of-view of the dominant society. Books about Native American history have been influenced by a multitude of interests: written through the eyes of colonizers, military leaders, missionaries, traders, and government officials–all with their own specific interests and purposes for writing. If Navajos and other native people had a written language earlier, history books might well be different, incorporating the viewpoints of the indigenous peoples.

Many native people feel that standard history texts do not contain the indigenous point of view. There are significant discrepancies between the written materials in libraries and the histories passed down for generations by Native Americans through word of mouth. Most history books traditionally have emphasized the conflicts between native peoples and the European newcomers, primarily military and social conflicts. The native perspective instead emphasizes social interconnections and the strong relationships with nature and spirit valued by most Indian groups.

The history of Utah Navajo people begins with oral history: origin stories and early interactions with Anasazi, Pueblo, and other peoples. Written history since the 1 700s has documented Spanish and Mexican relations with Navajos, followed by American military invasion and colonization of Navajo lands. The history of Utah Navajos differs somewhat from that of other Navajos due to years of their interactions with Utes and Paiutes as well as Mormon and non-Mormon settlers, ranchers, and traders. Many Utah Navajos did not go to Fort Sumner during the time of the Long Walk of the 1860s, hiding in various canyons of southern Utah and northern Arizona.

This brief Navajo history will highlight significant events that occurred from prehistoric times to the present, divided into seven main categories:

1. Traditional Oral History–Stories of the Ancestors

2. Athabaskan heritage and migration theories

3. Pueblo Indian Relations

4. Spanish and Mexican Colonial Period

5. United States Military Conquest: The Long Walk and Fort Sumner Incarceration

6. American Colonization

7. Development of the Navajo Nation as a Sovereign Entity

Traditional Oral History–Stories of the Ancestors

Navajos, like all other indigenous people, have their own stories about the creation of the world and their place in that world. These stories have been handed down for countless generations, primarily by oral history and song. Because these stories were not written in books hundreds of years ago, western historians refer to them as pre-history–essentially the time before the coming of Europeans to the Americas.

Navajo origin stories begin with a First World of darkness (Nihodilhil). From this Dark World the Dine began a journey of emergence into the world of the present. In this First World there was only darkness, moisture, and mist. The mists were associated with the four directions: east, south, west, and north, and they had additional associations with colors: white, blue, yellow, and black. In the world of darkness there was water and land. Insect-like people lived in the first world, along with other spiritual beings. Ant People were among the first to dwell in this world; other spiritual beings in the dark world included Underwater People, Water Spirit or Water Monster, and Fish People.

Other Diyin Dine’e, referred to as Holy Beings or Spirit Beings, also dwelled in the First World. They were formed of mist but had human physical attributes, as well. Among these beings, some of the notable were First Man, First Woman, First Boy, First Girl, Beegochidii, Black God (Haashch’eeshzhini), Talking God (Haashch’eelti ?i), Hogan God (Haashch’eehwaan), and Coyote (Ma’ii). These beings or people lived with the Insect People.

Where white clouds and black clouds met, First Man was formed, and where blue clouds and yellow clouds met, First Woman was formed. All the beings in the First World were able to understand each other, implying a universal language by which they communicated. Eventually there was a lot of disagreement among the beings and they were forced to leave the First World, through an opening in the east. With them, however, they took all the problems they had created.

They emerged into a Blue World (Ni hodootliizh) , the home of blue-colored birds. These blue-colored beings included blue birds, blue jays, and blue herons. Other animal beings also lived in this world: bobcats, badgers, kit foxes, mountain lions, and wolves. Again, the beings quarreled and were forced to leave, going in a southern direction, taking their problems with them.

The people next emerged into a Yellow World (Niholsoi), meeting other animal beings: squirrels, chipmunks, mice, turkeys, deer, spider people, lizards, and snakes. The people still had their problems and quarrelsome behaviors. Eventually the men and women separated and began to live on opposite sides of the river. During the time of the separation of the sexes, the men survived by hunting and planting; however, the women did not fare as well–they were not skilled hunters and did not tend to their fields. After four years the women were starving and begged to return to the men. After the sexes were reunited, Coyote stole the Water Spirit’s baby. As a result, the Water Spirit got very angry and caused a great flood.

The people escaped the flood by climbing through a huge reed, led by the locust. The last animal to climb out of the reed was the turkey. It is said that as he was climbing up, the foamy water of the flood was rising and lapped at his tail, thus creating the white-streaked tail feathers of the wild turkey. The beings emerged at a place called into the White, or Glittering, World–the present world. Some stories say this place of emergence was in the mountains of Colorado, near Durango.

At this point, the small group had grown to include other holy beings, including insect beings, bird beings, and animal beings–each being contributing to the planning and organization of the world. First Man formed four main sacred mountains from the soil that was taken from the lower worlds and these became the sacred boundaries of the Dine world. Each mountain was fastened to the earth in a unique way and given special adornments and empowerments.

Although each mountain was given specific natural endowments, nevertheless, all of the mountains were also endowed with all of the natural beauties and powers of the universe. The complexity of understanding nature through relationships and interrelated processes of all things is the basis and foundation of the Navajo view of the sacred mountains. The deep natural communication that is ongoing in the universe can be expressed through many concepts. In this case, it is expressed through the four sacred mountains.

There are many stories about this time related to teachings of the hogan, the sweat lodge, daylight, and night. Teachings about the stars, sun, and moon were given at this time to the people. Eight main constellations were created by the Holy Beings: the Male Revolving One, which includes the Big Dipper; the Female Revolving One, part of Cassiopeia; the Pleiades; First Slender One, which includes Orion; Man with Legs Spread Apart, which includes Corvus; First Big One, which includes the upper part of Scorpius; Rabbit Tracks, which includes the lower part of Scorpius; and Awaits the Dawn, the Milky Way.

The Holy Beings had an orderly plan for placing the stars in the Upper Darkness and were proceeding to place the stars carefully one by one, when mischievous Coyote grew impatient and flung the buckskin holding the stars into the sky. That is why, according to the story, there are many stars placed at random in the sky. What Coyote actually did was to create chaos, but out of that chaos emerged an order.

Sometime after the emergence to the Glittering World, a few women gave birth to monsters, as a result of transgressions that had occurred in the previous world. As the monsters matured they began to prey upon the people, causing the death of children and creating a climate of fear. When the monsters had killed off most of the young children, several events occurred which eventually resulted in the placing of the earth back into harmony. One morning in the pre-dawn, a baby was found on top of Gobernador Knob. Talking God found the baby girl and brought her to First Man and First Woman to raise. She grew in a spiritual way, attaining maturity in twelve days. The baby became known as Changing Woman (Asdzaan Nadleehe), the spiritual mother of all Navajos. When she came of age, she had the first puberty ceremony (kinaalda).

Sometime later she became impregnated by the Sun. She gave birth to twin sons, later called Monster Slayer (Naaee’ Neezghani) and Born for Water (Tobdjishchini). As the twin boys grew up, they became curious about who their father was. Very reluctantly Changing Woman told them that their father was the Sun. Aided by spiritual beings like Spider Woman, the boys traveled to the home of the Sun. There they went through a series of endurance tests to prove that they truly were sons of the Sun. After they passed all the tests devised by the Sun, they were offered many material goods; but they refused the goods, saying they only wanted the spiritual weapons of lightning (Atsiniltl’ish K’aa’–male zigzag lightning arrow and Hatsoo’alghal K’aa’–female straight lightning arrow) to kill the monsters (naaee’) on earth.

When the twins returned to earth they used their weapons and killed the monsters, beginning with the giant Ye’iitsoh La’i Naaghai, thus making the earth safe again for human beings. Several of the monsters were spared by the twins, however. These monsters pleaded for their lives, saying they carried important lessons for humans. The monsters that were allowed to live included Hunger, Poverty, Lice, Old Age, and Sleepiness.

When the world was safe, the Diyin Dine’s left and Changing Woman went to a home prepared for her by the Sun, somewhere in the west. She created the four original Navajo clans from her body, and later people of these four clans migrated back to the land of the four sacred mountains. The origins of Navajo ceremonies developed from these sacred narratives, and those teachings are still honored today. There are many Navajo stories about the return from the west and how other clans were created and merged. All the stories speak of migrations and adaptations.

Athabaskan Heritage and Migration Theories

There are many theories as to where Native Americans including the Navajos actually came from. It is not known for certain where the Navajos came from before they settled in the Southwest. Most anthropologists and archaeologists believe that Navajo people came from the north or central Asia, thousands of years ago. They say that a people they call Na-Dene crossed the Bering Strait during the last Ice Age when there was an ice passage between the hemispheres and arrived in what is now called Alaska. Over the centuries, they migrated south, spreading out throughout Canada and the United States, even into northern Mexico. Among the Na-Denepeople were Athabaskans and, according to this theory, these are supposedly the ancestors of the Navajo. Somewhere on their journey from the far north, Athabaskans separated into two main groups–Northern and Southern Athabaskans. Although there is little physical evidence, such as artifacts, for this anthropological theory, there is much linguistic evidence. Even today, similar words exist among Northern and Southern Athabaskans.

Other approaches to the anthropological migration theories emphasize physical human evidence, interpreted to support the Bering Strait migration theory. There are striking physical similarities between Navajo and Tibetan people, for example, as well as between Navajo and Mongolian people.

The group of people known as Southern Athabaskans migrated to the south over the course of hundreds of years, according to anthropological theory. They may have traveled south along the Pacific Coast, or they may have traveled through the Great Basin near the vicinity of present-day Salt Lake City, or through the Rocky Mountains or the western Great Plains. The migrations may have taken hundreds or thousands of years. Most probably people traveled in small nomadic groups, living primarily as hunters and gatherers. At some point, Navajos split off from other Southern Athabaskans. Some historians believe that Navajos migrated into the Southwest sometime between A.D. 200 and 1300. Some of the other Southern Athabaskans went as far south as northern Mexico, while still others were the ancestors of modern-day Apaches, Hoopa, and other tribes. Among the languages of Navajos and Apaches there are many linguistic similarities, and, in some cases, there are even similar spiritual and ceremonial practices. Apache Sunrise ceremonies are similar to the Navajo Kinaalda, for example, both being puberty ceremonies to acknowledge the coming of age of young women. Both are based on oral story traditions of Changing Woman. Navajo ancestors may have intermingled with ancient Fremont Indians and with the Anasazi.

Although many Native Americans are well aware of the anthropological theories of migration, most traditional origin stories do not make any specific mention of crossing a passage like the Bering Strait and traveling south from a land of ice. Most native stories tend to emphasize how the people originated from what they now identify as their homeland. Navajos have passed down elaborate and complex origin stories describing their emergence from the earlier four worlds into the land of the four sacred mountains of the Southwest. For many Navajo students these two theories are difficult to reconcile, with schools teaching the anthropological version while at home the young people learn the traditional origin stories.

Navajo origin stories, as mentioned, speak of how Changing Woman created the original four clans and how the Navajo people returned from the west to their homeland in the Four Corners region. The stories also speak of a group separating from the main group of Navajos and traveling north. These Navajos are referred to as the Dine Nahodloonii. It is said that if the two groups ever meet again, misfortune could occur. Among the complex Navajo migration stories, however, there are no stories of Navajo ancestors coming down south from the far north. Some Athabaskan groups–for example Jicarilla Apache–do have other migration stories that include references to a journey from the far north. The Mescalero Apache refer to an earlier time and place—a Land of Ever Winter—and to their journey south from there.1 Many of the details of these oral stories are now being lost to the present generation.

Pueblo Indian Relations

After the Navajos returned from the west, according to oral tradition they settled in an large area they called Dinetah, which is located southeast of present-day Farmington, New Mexico. There is abundant archaeological evidence of Navajo occupation throughout Dinetah. Ancient hogan structures, sweathouses, and fortresses exist alongside petroglyphs and pictographs throughout the area. The rock art illustrates Navajo ceremonial arts that are clearly recognizable by Navajos today.

It is not certain when Navajos occupied Dinetah; but, based on available archaeological and anthropological data, it has been assumed that it was around A.D. 900 to 1525.2 Navajo oral stories speak of a relationship with the prehistoric Anasazi while Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon was being built, which suggests Navajo presence in the area as early as A.D. 900. The Navajo word for corn is naaddaa, referring to an enemy’s or non-Navajo’s plant food.3 This suggests that other people in the area were growing corn before the arrival of the Navajo and that there were adaptive relationships between Navajos and Anasazi. The word Anasazi is also a Navajo word, referring to ancient relationships with an enemy or, at the least, a non-Navajo group. Since the Anasazi are generally believed to have left the Four Corners area by 1300, this suggests that Navajos may have been in the area prior to the Anasazi migration out of the region.

Harry Walters, a Navajo scholar at Dine College, Tsaile, Arizona, writes: “Navajo oral history has no account of early Navajos living further north of the southern Colorado mountains. The emergence into this world, from three previous worlds beneath the surface of this earth took place somewhere in the mountains near La Plata, Colorado. According to the Navajo tradition, this was the beginning of the Earth Surface People.”4

Regardless of how or when Navajo ancestors entered the Four Corners region, many sources agree that there were extensive migrations and intertribal adaptations between and among Navajos and Anasazi (ancestral Pueblo people) and among Navajos and historic Pueblo peoples. “Everywhere the Athabaskans went” comments Harry Walters, “they were influenced by people they encountered and they themselves also introduced new ideas and technology to new areas. The Athabaskans were responsible for the introduction of the woodland pottery, the hogan, tipi, shield and barbed-point bone and flint points and the moccasins to the southwest.”5

In southeastern Utah, archaeologists suggest later dates for the arrival of the Navajos. In San Juan County, the earliest existing known Navajo site (a hogan site in White Canyon, west of Bear’s Ears) has a tree-ring date of 1620. In several Spanish maps dating from the 1660s Navajo territory was described as extending “well north” of the San Juan River. Early treaties and maps made reference to Navajos occupying areas of Utah as far north as the present town of Green River.

From the early 1500s to the late 1700s Navajos occupied the area of Dinetah. This period has been generally divided into two phases: the Dinetah Phase, from 1550 to 1700, and the Gobernador Phase, from 1700 to 1775. The major difference between the two phases results from the aftermath of the intertribal Pueblo Revolt of 1680, when many Pueblo people moved into Dinetah to avoid the wrath of the returning Spaniards.

Spanish and Mexican Colonial Period

Spaniards had arrived in the Southwest in 1540 with the army of Francisco Vasquez de Coronado. Almost fifty years earlier, in 1492, Christopher Columbus had landed on an island in the Caribbean Sea, “discovering,” he said, a “new world.” The term New World seems ironic, since North and South America were heavily populated by native people, and had been occupied for more than 12,000 years. The Spanish conquistador Hernan Cortez landed on the eastern coast of Mexico in 1519 and conquered the Aztecs and other native groups. The Aztec leader Montezuma was killed at this time, but later legends told of his return and recapture in southern Utah. His name lives on in the present town of Montezuma Creek, Utah, and that of his people in Aztec, New Mexico. A motel in Bluff, Utah, embraces the myth with the name Recapture Lodge. The name of Cortez lives on through the town of Cortez, Colorado, just east of Montezuma Canyon.

The first Spanish expedition to come into the American Southwest was under the leadership of Coronado. He was guided by a black slave named Esteban, who was one of the few survivors of a Spanish shipwreck off the coast of Florida in 1528. Esteban journeyed throughout the southeastern part of the United States for almost eight years until he found his way to Mexico City. He later joined Coronado’s expedition into the Southwest and was killed in a confrontation with Zuni Indians, ironically while proclaiming himself immortal.

Coronado spent several years roaming around the Southwest searching for gold and the fabled Seven Cities of Cibola. He visited Zuni and Hopi pueblos and undoubtedly came into contact with Navajos at this time. The Navajo name for Spaniard is Nakai, meaning “those who wander around,” referring to the various expeditions that frequently came into Navajo country. The first recorded contact between Navajos and the Spanish invaders came in 1583 in the area of Dinetah. An expedition led by Antonio de Espejo refers to the Querechos Indians near Mt. Taylor. The Spanish also at times referred to Navajos as “Apaches de Navajo,” leading to some confusion for future historians.

For the next hundred years the Spanish attempted to colonize the Southwest. Juan de Onate came to the Rio Grande in 1595 with the intent to colonize the area. His powerful army subjugated many of the Pueblo Indians. Any Pueblo resistance was dealt with by severe and brutal measures. In one infamous incident, residents of Acoma Pueblo were attacked by Onate’s army; adult males who survived the attack were punished and tortured by having one foot cut off and being enslaved. Women also were enslaved, as were older children, some for as long as twenty-five years. Countless other stories of Spanish brutality exist among the Pueblo people, and even today Onate’s name is held in opprobrium among the Navajos and Pueblos.

Along with military colonization came forced Christianization. The native inhabitants were coerced into accepting Christianity, while their own religious practices were forbidden. Spanish records show that many thousands of Indians were baptized. Some reportedly were killed soon after the baptismal ceremony. There was an attempt at complete Spanish domination. Many Native Americans were enslaved, and some were sent to work in mines as far away as Mexico. There are no records of any returning to their own country. The king of Spain claimed the land of the Southwest, including most of present-day Utah, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, and California, awarding large land grants to the conquistadors, missionaries, and colonizers.

A tremendous depopulation of native peoples occurred at this time. Millions of native people died throughout the Americas from warfare, slavery, and diseases brought by the Spanish invaders. The native people had no immunity to many of the diseases, such as smallpox, brought by the Spaniards. In some cases, entire villages and tribes across the continents of North and South America were wiped out by disease.

By 1680 the Pueblo Indians, aided by various Navajo and Apache groups, had had enough of the brutality and atrocities of forced subjugation. Under the leadership of a medicine man from San Juan Pueblo named Pope, native people rose up in defense of their rights. This has been called the Pueblo Revolt by historians, but from a native perspective it might more appropriately be termed a war for independence.

The Pueblo Revolt of 1680 was an extreme reaction to an extreme situation. It is estimated that around 400 Spaniards were killed in the first days of the revolt. The rebellion became so widespread that the Spanish were forced out of the territory and returned to Mexico.

In 1693 the Spanish returned to the Rio Grande Valley. By this time the Pueblo people were no longer united and, as a result, the Spanish soon reconquered the area. Many natives fled the pueblos during this period, taking refuge among the Navajos in the Dinetah area. There was an intermixing of Navajo and Pueblo cultures during this time. Many Navajo clans are descended from Pueblo ancestry, which have their roots in this era. Other Navajo clans such as Nakai Dine’e acknowledge their descent from certain Spanish and Mexican ancestors.

Social interaction among the various Pueblo Indians and Navajos intensified during this time. Navajos began to rely more on farming and sheep herding as a way of life. It is believed that much cultural and spiritual sharing took place as well. Even today one can see remains of the ancient wood and stone structures that were constructed during this era. Fortresses on almost inaccessible cliffs illustrate the dangers faced by the people, while pueblitos, circular hogans built alongside square stone buildings, show the social interaction among cultures.

Eventually many of the Pueblo Indians returned to their old communities and learned to co-exist with the returning Spanish. Others remained with Navajo families, however, and gradually became adopted into the Navajo clan system.

Life became extremely dangerous in Dinetah. During the latter part of the 1700s the Spanish created alliances with the Comanches and Utes, and these combined with various French, Pawnee, and Pueblo interests were aimed at weakening and defeating the Navajos. Atrocities were committed on all sides. Constant raiding and slave-taking occurred. It is estimated that during the early 1800s more than 66 percent of all Navajo families had experienced the loss of members to slavery. Navajo children were taken from their families and sold at auction in Santa Fe, Taos, and other places. Others were sent deep into Mexico to work in the silver mines. Most never returned. Many Navajo families retell stories of slaves taken or escaping during this time.

In 1821 Mexico gained its independence from Spain; consequently, the Spanish government withdrew from the Southwest. Many of the people of Spanish origin remained, however, becoming Mexicans under the new regime. All of the people living in what became Mexican territory were proclaimed to be under the rule of the Republic of Mexico, including Navajos living in what is presently Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. This proclamation was a unilateral declaration made without Navajo consent.

Skirmishes, slave raids, and massacres occurred with increasing frequency. The Mexicans condoned and even increased raiding and slave taking efforts. Gradually Navajos continued to move out of Dinetah, populating areas such as Bear’s Ears in Utah, Canyon de Chelly, Mount Taylor, Navajo Mountain, and as far west as the Grand Canyon.

Many treaties were hastily written and just as hastily discarded. Neither the Spanish nor the Mexicans understood the Navajo decentralized political structure, whereby no one headman could speak or sign treaties for all Navajos. Another factor contributing to the lack of cross-cultural understanding was language. Few Navajos understood Spanish or English, and certainly almost no Spaniards, Mexicans, or Americans could speak or understand Navajo. Apart from the language, few Europeans could even begin to understand the Navajo worldview. European invaders had their own policies and priorities: to Christianize, to enslave, to take over the land. None was based on understanding or reciprocity between cultures.

As hostilities increased during the Mexican era, from 1821 to 1848, more treaties were written, but they all failed to bring about a lasting peace. Military expeditions were sent into Navajo country with increasing frequency. These expeditions were often accompanied by native scouts and volunteer militia from New Mexico. One of the first known expeditions entered in 1823 into what is now Utah. Jose Antonio Vizcarra commanded an expedition of 1,500 men, setting out from Santa Fe with orders to punish certain Navajos and bring about peace. Vizcarra is known to have traveled through Oljeto Creek in southeastern Utah. At the same time, another Mexican force under Don Francisco Salazar entered into Utah following the trail to Bear’s Ears and fighting Navajos in Chinle Wash.6 Both Mexican military officers described seeing traces of Navajos fleeing north across the San Juan River into what is now Utah.

Many accounts written during the following forty years mention Navajos, Paiutes, and Utes traveling through and living in the area of southern Utah. In 1832, for example, Navajos were reported living north of the San Juan River. It is recorded that Hastiin Beyal was born at the head of Grand Gulch during this time.7 The grandparents of a Navajo man called White Sheep were born in the 1820s, one near Bear’s Ears and the other near the San Juan River. The Navajo headman K’aayelli was born around 1801 near Bear’s Ears. Kigalia Spring, north of Bear’s Ears, was later named after him. Another Navajo headman called Kee Diniihi was born in White Canyon in 1821. Navajos were reported living as far north as Monticello, Utah, in 1839, on a map drawn by a traveler, T.J. Farnam, and other trappers and travelers also mentioned Navajos in the area.8

United States Military Conquest: The Long Walk and Fort Sumner Incarceration

Although some of the following history does not directly pertain to Utah and Utah Navajos, the events are seminal in Navajo history, impacting profoundly all Navajos from the time of the Long Walk to the present. In 1846 the United States declared war on the Republic of Mexico. Colonel Stephen W. Kearny entered New Mexico in August and took over the province with no resistance from the Mexican troops there. The Navajos first thought that the Americans would be allies with them against their common enemy, the Mexicans. To their surprise, however, the Americans sided immediately with the Mexicans, declaring that they would protect Mexican colonists against all hostile Indians, including Apaches and Navajos. Kearny dispatched Colonel Alexander Doniphan to lead an armed expedition into Navajo country. This was the first U.S. military expedition into the heart of Dine Bikeyah, Navajo land. Part of the expedition followed the San Juan River southwest towards Chinle Wash. Utah Navajos may have seen American soldiers for the first time during this period.

By the time of the arrival of the American soldiers, hostilities were so rampant on all sides that attempts by the Americans to enter into meaningful peace treaties with the Navajo people were not worth the paper on which they were written. As was the case during the Spanish and Mexican occupation of the territory, treaties were written and broken almost immediately by one side or the other. A close reading of Spanish, Mexican, and American military and governmental documents indicates that some of the Europeans shot Navajo and Apache men and women on sight, while children and babies were taken captives and sold into the slave markets.

One of the first military projects of the Americans was to build a fort–Fort Defiance–in Navajo country. There were regular negotiations between American officers and Navajo leaders. Although Navajos were not centralized in the European sense, they did come together into groups by clan and close-knit families. They were led by various leaders often referred to as haske nahat’a (warrior leaders) and hozhooji nahat’a (peace leaders). The best-known leader of this time was Naabaahni (Narbona). Today these leaders are commonly known by their Spanish names, but they had various Navajo names by which they are known among traditional Navajos: Barboncito (Hastiin Dagha, Man With Mustache, and his warrior names, Haske Yil Deeya and Hashke Yil Deswod) from Canyon de Chelly, Zarcillos Largos (Naat’aani Naadleel, Keeps Becoming Leader), and Ganado Mucho (Totsohnii Hastiin). Manuelito (Hastiin Ch’ilhaajinii, Man of Dark Plants Emerging) also became a well-known warrior and leader. He was born in Utah, near Bear’s Ears and is still known among the Navajo as Askii Diyin (Holy Boy) and Ch’ilhaajin.

Navajos refer to the 1850s and early 1860s as a troubled period–Nahonzoodaa’–during which they had to constantly move around in defense of their livestock and families. They had to keep ahead of their enemies at all times. No permanent structures could be built, and their hogans and cornfields often were discovered and burned. Sheep and horses were stolen. Families were massacred and children were taken to be sold. Enemies came from all directions: Utes, Comanches, Jicarilla Apaches, Zunis, New Mexicans, and Americans. Alliances were constantly shifting. Americans, French, Spanish, and in some cases Mormons, reportedly furnished the Utes, Comanches, and Pawnees with guns, while the Navajos had to fight primarily with bows and arrows and spears.

With the coming of the Civil War there was a temporary withdrawal of American soldiers from the area, and many Navajos probably believed that they had seen the last of the Americans. But even before the war ended U.S. soldiers returned to subjugate the Navajos. The United States declared war on the Navajos under the military command of General James Carleton. Many Americans wanted more than a Navajo defeat–they also wanted the land of the Navajos for grazing and mining. Carleton in particular was interested in minerals. He felt that if the Navajos were removed far from their homeland, Americans could mine their territory and men like himself could reap great profits. To further this scenario, Carleton immediately reserved an area in New Mexico for the removal of the Navajos. This was Bosque Redondo (Round Grove) on the Pecos River. The area was later called Fort Sumner by the Americans and Hweeldi by the Navajo.

Carleton hired Christopher “Kit” Carson, a former Indian fighter and Ute agent, to help carry out his plan. Carson’s quite ruthless “scorched earth” policy was highly effective. Carson entered Navajo country in the summer of 1863 with a force of about 700 soldiers, Indian scouts, and New Mexico volunteers. Wherever he went, he gave orders to torch the Navajos’ homes, burn their cornfields, cut down peach orchards, destroy squash and melon fields, and take the livestock. Soon food became very scarce and the Navajos began to experience starvation. Many were forced to eat the limited wild game, cedar berries, pine nuts, yucca fruits, wild potatoes, and other wild foods available that fall.9 It was all-out war. On every side the enemies of the Navajos were pressing in and aiding the soldiers, including Ute, Hopi, Pueblo, and Zuni scouts, some disaffected Navajos, along with various Kiowas, Comanches, and Apaches. Not all the Pueblo people were enemies of the Navajo, however. Some Navajos took refuge at Jemez Pueblo as well as with other Pueblo groups where there had been centuries of intermarriage and adoption.

The Mescalero Apaches were also at war with the U.S. government and were the first group to be taken to Fort Sumner. Kit Carson made his headquarters at Fort Defiance and began to concentrate his efforts in the Canyon de Chelly area, the assumed stronghold of the Navajo.

By December 1863 the Navajos were in desperate shape. They were poor and hungry and the slave raiding had done much damage. It has been estimated that over one-third of the Navajos were enslaved in New Mexico during this era. Resentment over the slave trade was very high among the Navajos, as it was among the New Mexicans and Pueblo people who had suffered from Navajo raiding. In comparison with the thousands of enslaved Navajos, however, the number of slaves taken by the Navajos was limited.

Kit Carson continued to pursue his strategy of forced starvation. He ordered his men to destroy all waterholes and take all horses, cattle, sheep and goats. He attempted to convince the Navajos that they would be safer under his protection and that they would be well fed by the U.S. Army. Eventually many of the Navajos simply gave up and surrendered. They were ordered to gather at Fort Defiance and traveled in groups the more than 300 miles to Fort Sumner.

The winter of 1863–64 was extraordinarily cold. Most of the Navajo captives did not have adequate shoes or clothing. Carson had promised protection and food, yet what was given was grossly inadequate. The food that was provided was new to the Indians. They were not told how to prepare coffee beans and white flour, for example. People attempted to cook the beans, throwing out the water they were boiled in. People mixed flour with ash, not knowing how to cook with it. Many became sick and died from the unfamiliar food.

Almost every Navajo family has passed down stories about the horrors of the Long Walk. People were forced to walk twelve to fifteen miles a day. They were constantly fatigued and weakened by near starvation. Enemies followed the convoys, snatching captives almost at will. By the time the Navajo leader Barboncito reached Fort Sumner he had lost a son and a daughter to the slave raiders. He never saw them again. This occurred under so-called military-escort protection. The physical and psychological suffering was tremendous. The people were uprooted from their very way of life, since their life and spirituality were rooted in their land and mountains. When they passed Mt. Taylor, near present-day Grants, New Mexico, they were leaving the protection of the four sacred mountains. Oral traditions say that the Navajo people ceased to perform most ceremonies during the time of their captivity at Fort Sumner.

Clara Maryboy of White Rocks, Utah, recounted her great-grandmother’s experience. She told how each night the Navajos were covered with a large tarp which was nailed down over the captives.10 Others have told of elderly people and pregnant women who lagged behind and were shot. The weakest were left to die along the trail. The survivors were not allowed to go back and bury their family members and later told heartbreaking stories of hearing coyotes howl where their relatives had fallen.

There were several convoys of Navajo prisoners. The first convoy reached Fort Sumner fairly intact. Several other convoys which traveled later in March were hit by severe snowstorms, however, and hundreds of people died or disappeared along the way.

By November 1864 there were more than 8,000 Navajos at Bosque Redondo. It soon became evident that General Carleton’s concept of a Navajo utopia of farming, education, and civilization was not going to work out in the area. He was not even able to feed the large numbers of prisoners of war. People continued to starve after they reached Fort Sumner. The rations were inadequate, and the cornfields that Navajos were forced to plant failed three years in a row, due to natural disasters such as flooding from the Pecos River, severe hailstorms, drought, and insect damage. Firewood became increasingly scarce, and in some cases people reportedly had to go twenty or thirty miles for firewood. There was little shelter from the freezing weather and hot sun except holes that people dug into the earth. Carleton wanted Navajos to live in hastily constructed homes, but this was foreign to the Navajos, who also did not want to live where others had died. In addition, the Mescaleros and Navajos did not get along in the confined area. Disease was rampant; the Navajos had little immunity to the white man’s diseases such as smallpox, chickenpox, and pneumonia. Women had to prostitute themselves in order to provide food for their families, and venereal disease became another horror. The Comanches and New Mexicans were constantly raiding, raping, and taking slaves and livestock.

The military and civilian authorities in charge of the Navajo prisoners were constantly at odds. Corruption was widespread. Cattle, brought in to feed the prisoners, were sold by unscrupulous contractors for their own profit. Most of the appropriations were squandered or substituted with useless materials. Some food that was shipped in was contaminated. It was reported that flour was mixed with ground plaster and that dried bread was contaminated by rat droppings. Clothing and blankets were of poor quality. The water was highly alkaline and not good to drink or to irrigate crops. The physical and mental anguish of the prisoners was great.

The conditions at Fort Sumner were so deplorable that many Navajos risked slavery and starvation to escape. Many left the reservation; some were recaptured. The Mescalero Apaches all left as a group. One winter 900 Navajos escaped. The policy of General Carleton failed miserably, at a very high cost of lives and government resources.

There were many Navajos who never went to Fort Sumner. People hid out as far west as the Grand Canyon and as far north as Navajo Mountain and Bear’s Ears. Other small groups who had time to prepare were able to survive in remote canyons. Some escaped into Utah across the San Juan River. Haashkeneinii took his group from Monument Valley to a remote area of Navajo Mountain. He had learned in 1863 that both soldiers and Utes were coming to Monument Valley and had prepared his people to leave. They reportedly moved to the San Juan River, “moving at night and hiding by day.”11 Finally they reached Navajo Mountain, where they hid out until 1868. K’aayelii retreated to the area around Bear’s Ears and his descendants still tell stories today with pride about how he and his people never surrendered.

One of the most influential and powerful Navajo leaders, Manuelito, who was born in Utah, hid out for several years, avoiding the soldiers but being attacked several times by Ute forces. Finally, when his force was down to only a few wounded and starving warriors, he surrendered, his people taking pride in the fact that he was never captured.

The Black Hawk War began in central Utah in the mid-1860s, and fighting continued into the early 1870s. This was primarily a war of cattle raids, guerilla warfare, and pillaging led by Black Hawk, a charismatic Ute leader of a mixed and fluctuating coalition of Utes, Navajos, and Paiutes. Black Hawk led his forces into battle and conducted guerilla raids in order to try to feed his increasingly desperate people while also hoping to claim control of some traditional Indian lands. The Mormon settlers fought back but did not call in federal troops for aid. Brigham Young tried to minimize reports of the war, fearing that a large-scale war might lead to an increased federal presence in the region. Even today, this conflict is played down in Utah history books.12

Stories are told that members of other tribes came to Navajo leaders around Canyon de Chelly to ask for aid in their own fights against the white men. One even tells of a delegation of Lakota Sioux warriors who came to Navajos to request aid.13

By 1868 over 3,000 Navajos had perished at Fort Sumner and close to 1,000 had escaped. Finally, the corrupt administration of Fort Sumner came to the attention of high government officials and lawmakers. General Carleton was relieved of his command in August 1866 and an investigative commission traveled to Fort Sumner to see the conditions. They were horrified at the misery and corruption.

In late spring 1868 General William Sherman arrived to negotiate with the remaining Navajos at Fort Sumner. Barboncito was the chief spokesman for the Navajos. Many Navajos were ill and homesick. As a result of the negotiations, a treaty was signed on June 1 and ratified by President Andrew Johnson on August 12, 1868.

The treaty negotiations were carried out through three languages, a cumbersome interpretive process. Statements made in Navajo were translated into Spanish by Jesus Arviso, a former slave, and from Spanish to English by James Sutherland.14 When statements were made in English, the process was reversed. Often the meaning was obscured during the translation process. Navajo and English languages are very different from one another and accurate translation is extremely difficult. It is probable that neither group completely understood the other.

Barboncito was the lead negotiator for the Navajo. Many of his statements have been preserved to the present. “Our grandfathers had no idea of living in any other country except our own,” he told General Sherman. He described the living conditions of the Navajo at Bosque Redondo as a great impoverishment. Now they had nothing to eat and nothing to wear except gunnysacks. They had sunk into absolute poverty and despair. He could no longer sleep at night because of the condition of his people and he hated the trip to the commissary for food because he did not like to be fed like a child. “I hope to God that you will not ask me to go to any other country except my own’ he stated in response to the peace commission’s tentative plan to send all native peoples to reservations in “the land of the Cherokee” in present-day Oklahoma.15

General Sherman was struck by how the Navajos had “sunk into a condition of absolute poverty and despair.”16 Much of Sherman’s knowledge came from a sympathetic agent at Bosque Redondo. Agent Thomas H. Dodd had reported to Sherman that the Navajos had worked diligently at their fields but that each year the crops were destroyed by insects, floods, drought, and the unproductive alkaline soil. The peace commission finally decided to allow the Navajos to return home.

The Treaty of 1868 was and remains a very important document for the Navajo people. The treaty recognized the sovereign status of the Navajo and was a legal compact between two sovereign nations. With the signing of the treaty, Navajos were finally free to return to their homeland.

On June 18, 1868, the Navajos finally began their journey home. The column of returning Navajos was more than ten miles long, with 50 six-mule wagons. It has been said that when the people saw the peak of Mt. Taylor, the sacred mountain of the south, tears of grief and joy were shed and many prayers were said as they re-entered into the land of the four sacred mountains.

The return route led through Albuquerque. Navajos began arriving in the Fort Defiance area in late July, ending a hot, tiresome five-week journey. Overriding everything in the minds of the Navajos was the fact that they were finally allowed to return to their beloved homeland, even though it had been significantly reduced to less than one-fourth of their original holdings.

American Colonization

Although the Navajo people were free to return home, there were many difficulties ahead. The U.S. government had promised to feed the people, under the trustee status of the treaty, but the promised annuities and food did not all come as promised. Many families remained at Fort Wingate and Fort Defiance waiting for livestock and farming supplies. When sheep and goats were finally distributed to families, the people protected and cared for them. Even though families were hungry, they did not butcher the sheep, wanting to build up their small herds. Eventually the livestock multiplied and the people became increasingly self-reliant.

The increases in livestock required more pasture and demanded more mobility, so as not to deplete the land. Out of necessity, the Navajos began going out farther than the treaty boundaries. At the same time, white ranchers and homesteaders began to move deeper into the public domain lands, leading to continual conflicts. This was the case in southern Utah as on the rest of the reservation. Navajos began to cross the San Juan River and settle around Bluff and Montezuma Creek. They already had a long history of living near Bear’s Ears, Navajo Mountain, and Monument Valley. They came into conflict with Utes in some instances and there were escalating hostilities and confrontations. There also were conflicts with whites, including ranchers, Mormon homesteaders, and some traders. Many groups were vying for the land near the San Juan River.

Land ownership was a concept foreign to the Navajo, as it was to most Native Americans. Navajos did not understand why they needed to apply for land that they felt had always belonged to them. Besides, how could you own the land any more than you could own the stars and the clouds? Furthermore, Navajo hogans and shelters did not qualify as legal land improvements, as did the buildings of the white men, so Navajos often lost control of their land. As the conflicts escalated, so too did the raiding. Manuelito was put in charge of the first Navajo police force, which was developed with the primary charge of returning livestock taken from white settlers. It was felt that a Navajo policeman could better explain the reasons behind the law enforcement to other Navajos than could a non-Navajo-speaking government authority.

The period between 1870 and 1900 saw many changes. The increased development of a barter economy began to change the dynamics of the traditional economy, and a system based on money began to develop. People began trading for outside goods. Navajo rugs were exchanged to white traders for desired goods and services. Traders built larger trading posts in the area and brought in more and varied goods. Traders also began to influence some of the patterns of rugs being woven. Brightly colored aniline dyes and Germantown yarns changed the look of Navajo rugs. In many cases, the women’s rugs were the family’s main trade item. Silversmiths became increasingly skilled but for some years most of their silverwork was designed and created for their families, with little going to the trading posts.

Another force that impacted Navajo life in general (though not as much in Utah) was the construction of railroads, particularly the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad as it crossed New Mexico. Along with some wage-earning jobs, however, the railroad brought whiskey and the beginnings of a serious alcohol problem throughout the Southwest.

Many of the promises made to the Navajos in the Treaty of 1868 were never fulfilled. Most of the Indian agents were apathetic; in some cases, they were even unsympathetic to their Navajo charges. There was tremendous turnover among the agents. This was not only a Navajo problem, it was true on the majority of Indian reservations across the country. Several of the Navajo Indian agents, however, tried to get the federal government to fulfill its obligations. During several hard years with a severe shortage of food and commodities due to drought and other natural disasters, Navajos were starving. Agent Dennis Riordan was concerned and frustrated in the 1880s. In one of his reports to Washington, he described the situation:

The reservation embraces about 10,000 square miles of the most worthless land that ever laid outdoors…. The country is almost entirely rock. An Illinois or Iowa or Kansas farmer would laugh to scorn the assertion that you could raise anything there. However, 17,000 Indians managed to extract their living from it without government aid. If they were not the best Indians on the continent, they would not do it…No help is given to the indigent and helpless Indians, the agent being compelled to see them suffer under his eyes or else to supply the much needed articles at his own expense…The United States has never fulfilled its promise made to them by the treaty.”17

Indian agents could rarely cover all their assigned territory. The Navajo Reservation was large and agents could only travel by horseback. Also, many agents simply did not want to leave the safety and comfort of their posts. Consequently, many Navajos had little or no contact with agents as the years went by. Agents usually did not stay long in Navajo territory. The turnover was very high. The isolation was difficult for the agents’ families and the pressures were great. Although they were backed up by the military, when necessary, they were often the only source of government authority in the area, and their resources were severely limited. Their effectiveness also was weakened by the lack of food and supplies they could obtain. In addition, not all Navajos recognized or truly consented to their authority.

As more and more Navajos began to move out of the ceded boundaries established by the treaty, agents began to realize that the reservation needed to expand in order to accommodate the growing Navajo economic needs. Several additions were made to the original treaty reservations. Lands in northern Arizona, New Mexico, and southeastern Utah were part of this expansion. A significant addition to the reservation came with an executive order of 1884, when much of what is now Utah Navajo land was added. Areas including the Aneth Expansion (1905) and the Paiute Strip (1933) were added, taken away, and then re-added according to political and economic whims, eventually resulting in the reservation boundaries of today.

Life 100 years ago in southern Utah was often uneasy, with frequent hostilities among Navajo, Utes, Mormon settlers, other Anglo ranchers and homesteaders, and, increasingly, prospectors and miners. Shootings and other physical violence were common. In some cases both Mormons and non-Mormons were accused of supplying guns to the Navajos to further their own plans. H.L. Mitchell founded the area’s first white settlement in 1878, at the mouth of McElmo Canyon. Montezuma Creek was settled in 1878 and Bluff was founded by Mormon settlers in 1880. Increasingly, all the white settlers wanted the Navajos to be contained on the south side of the San Juan River. Mormons and non-Mormons alike wanted the north side of the river and all the water rights. Much of the conflict was based on greed, observed army officers who were often called in to settle armed disputes. “My sympathies are very much with the Navajos,” stated a Captain Ketchum from Fort Lewis about one incident. “The people who complain against them are the very worst set of villains in existence.”18

Other conflicts took place in the Monument Valley area, where four prospectors were murdered over a period of time, all trespassing in a sensitive area where they had been advised they did not belong. Headmen in the area did not want precious metals found in their area, because they did not want the rush of miners that would follow a find. The prospectors killed in late 1879 or early 1880 were James Merrick and Ernest Mitchell, son of H.L. Mitchell who had settled at the mouth of McElmo Canyon. In 1884 two other prospectors were killed near Navajo Mountain, triggering a hunt for the suspected Navajos. No one was ever indicted for the murders.

Another shooting took place at Rincon, several miles west of Bluff, Utah. Amasa Barton, who ran a small trading post there, was murdered by Navajos. This incident almost precipitated a war when sixty angry Navajos rode into Bluff ready for a fight. As in much of the oral history of San Juan County, the Navajo and white settlers’ accounts of the incident differ somewhat.

Reformers began to emphasize the education of Indian people across the United States during the late nineteenth century. Christian denominations including Roman Catholic, Dutch Reformed, and Presbyterian churches took up the task of teaching various Indian groups. Even earlier, Navajo oral histories mention enishoodi (priests) working among them at Fort Sumner.19

Article VI of the Navajo Treaty of 1868 stipulated that education was to be compulsory for not less than ten years after the signing of the treaty. The government was to provide one schoolhouse and one teacher for every thirty Navajo pupils between the ages of six and sixteen, who could be induced or compelled to attend school. These provisions of the treaty were never fulfilled. In fact, many Navajos argue that the treaty obligations regarding education have never been fulfilled to this day.

Indian education was aimed at civilizing, “taking the savage out of the Indian.” Acculturation and assimilation into mainstream society were the ultimate goals. Courts of Indian Offenses were established in the 1880s and 1890s with the purpose of abolishing all forms of Indian ceremony and “heathenish practices.” Offenders (practitioners of native spiritual practices) were incarcerated through these tribunals.

Complete assimilation into mainstream society was thought to be the salvation of the tribes. The aim was to educate the younger tribal members through inculcation of the western belief system and the English language. It was believed that the younger people would assimilate the new practices more readily and that eventually the old ways would become ways of the past. Across the United States, Indian children were taken from their homes and put into government-sponsored residential schools, many not returning home for years, if ever. The first Indian residential school was the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, founded by army officer Richard Pratt in 1875. The first students included prisoners from Plains tribes. Later, Indians from across the nation attended. In 1885 there were six Navajos attending the school, among them a son of Manuelito. Only one of the Navajo students survived to return to his people. Manuelito was distraught over the loss of his son and ceased being a strong advocate of that system of education.

The residential school system of the late nineteenth century is still a topic that evokes intense bitterness and anger among many native peoples. Many of the children died of diseases such as tuberculosis. Parents were not informed that their children were ill and were devastated to learn that their children had died and had been buried so far away. The schools were highly regimented, patterned after military institutions. Children were subject to strict rule enforcement. Their hair was cut as soon as they arrived and many were forced to wear ill-fitting shoes and clothes. Ornaments and spiritual paraphernalia were taken from them. For many of the students, cutting their hair was contrary to their spiritual belief, but they had no choice. Perhaps worst of all, the children were forbidden to speak their own language, the only language many knew. Breaking the rules brought severe physical punishment. Whippings were common, as was having one’s mouth washed out with soap. Some reportedly suffered sexual molestation at the schools.

The federal Indian education policy shifted several times in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. More schools were built on the reservations, closer to the students’ homes. The Presbyterian Board of Missions was the first religious group to be given permission to establish schools on the Navajo Reservation. The first school on the reservation was established at Fort Defiance. Parents were hesitant to send their children away to school, and it was commonly the sick, weak, and orphaned children who attended schools, leaving the healthier, more fortunate children at home to assist their parents with economic survival. Most Navajos did not know what an “English” education, as specified in the treaty, meant, and felt that what their children were learning at home was far more relevant to their lives. Since education was compulsory, however, some Indian agents tried to enforce attendance, even taking children from their homes. This naturally caused more disharmony and, in some cases, outright confrontation.

Although there was some support for education in general, there was also strong opposition to the forced attendance. Navajos began to evaluate the value of western education as they realized that the system was geared to the destruction of their traditional spirituality and ways of life. Students were told that their ceremonies were mere superstition.

Students who were educated in the system often no longer fit into the traditional society. Jobs were limited both on and off the reservation, and often the educated students were caught between two worlds, belonging to neither. They became victims of the system. Today, Navajo educators advocate the learning of one’s primary language well, in order that the deeper thinking and consciousness of the culture can be expressed. Children who have neither a complete grasp of English or of the Navajo language have severe limitations in communication. That was often the case with the earliest Navajo students.

Day schools eventually were opened in many places on the reservation, enabling students to be educated closer to home, in accordance with their parents’ desires. In 1906 the town of Bluff requested a school and a teacher for Navajo children. The Indian agency, however, was not able to fund a school. It was decided that Utah Navajo students would attend school at Shiprock, in northwestern New Mexico, which in those days before the automobile was a long journey away.

Influential Navajo leaders such as Ba’ililii reacted strongly. Ba’ililii was a spiritual leader who took an extreme position, wanting a return to the traditional teachings. He and his armed followers issued threats in reaction to the announced educational policy.

Military troops were brought in from Fort Wingate to apprehend the protestors. They attacked a hogan south of Aneth, where Ba’ililii was performing a ceremony. During the skirmish several Navajos were killed. Ba’ihii and other followers were captured and spent several years in prison at Fort Huachuca, in southern Arizona. Later, the court decided that the Navajos had been imprisoned without due process. The case went to the U.S. Supreme Court and the Navajos were acquitted.

During this time the formation of a political structure patterned after the Euro-American political system was slowly evolving. In 1901, five governmental agencies were created, dividing the reservation into geographic districts for more effective regional governance. The Northern Agency comprising the Utah section was eventually centered at Shiprock. Utah Navajos even today are administered through the jurisdiction of the Shiprock Agency. John Hunter, Superintendent of the Leupp Agency developed the beginnings of a chapter system of government in 1927. Today there are 110 chapters of the Navajo Nation.

The first legislative council of the Navajo people was organized in 1923, more in response to outside business interests than to Navajo desires to create their own tribal government. It had long been suspected that oil and valuable minerals were located in the Four Corners area, primarily in southeastern Utah and near Shiprock. Prospectors had been prowling around the area illegally for years looking for gold, silver, gas, and oil. The Midwest Refining Company first discovered oil in 1922, thus initiating a demand for oil leases from the tribe. Many oil companies were anxious to begin exploiting the area and pressed for a legal body that could approve business leases. The Navajo Treaty of 1868 had stipulated that no legal decisions could be made without the consent of 75 percent of all Navajo adult males.20 Businessmen realized that it would be next to impossible to gain the consent of that many Navajo males, so they pressured the federal government to create a business council which supposedly would be representative of the Navajo males.

The first business council was a forerunner of the present-day Navajo Tribal Council. The first chairman was Chee Dodge, who was one of the few Navajos who could speak both Navajo and English. The three handpicked men who were selected to comprise the first business council were asked to sign off on the mineral leases. There were legal questions, however, as it was recognized that this small business council was not truly representative of the Navajo people. At the first meeting, the Special Commissioner to the Navajo Tribe was given the authority to sign all future oil and gas leases which the council might grant on the reservation. In addition, the U.S. Secretary of the Interior was authorized both to advertise and to approve future leases granted by the council. Everything was carried out under the supervision of the federal government. The council could not call a meeting without the approval of the Special Commissioner to the Navajo Tribe, nor could the council meet without him. In July 1923 the tribal council met for the first time, with six serving on the council, along with six alternates.

Since the small business council had been organized primarily in response to business desires for oil leases, it was not truly representative of the Navajo people. A set of rules and regulations were drafted by the federal commissioner in 1938 which became the foundation of the tribal council of the present Navajo government. The first council that was elected under the new rules and regulations was considerably larger and more representative than the previous business councils had been.

Many Indians across the United States, including some Utah Navajos, served in World War I. Largely in recognition of their military service the federal government granted citizenship to all Indians in 1924. This, however, did not mean that they could vote. In many states Indians had to bring lawsuits to be able to vote. Utah was the last state to allow Indians to vote. The ruling did not come until after a lawsuit in 1957.

The exploration for gas and oil caused some problems for Navajos. Congress passed a landmark law in 1933 that became the foundation for many lawsuits being filed in Utah today. The law stipulated that if oil or gas were discovered in “paying quantities” 37.5 percent of the production royalties would go to the State of Utah to be used for the education of Indian children as well as to build roads to benefit the Indians; 62.5 percent would go directly to the Navajo Tribe. Not until 1956 would “paying quantities” be found in Aneth, however.

There was a profound shift in federal Indian policy during the 1930s, due in part to the findings of the Merriam Report, an investigative report of reservation conditions completed in 1928 by the Brookings Institute. The report highlighted the abysmal conditions in which many tribal people were living and also provided guidelines for Indian policy for the next twenty years. The Indian Reorganization Act (IRA), also known as the Wheeler-Howard Act, of 1934 was one of the outcomes of the Merriam Report.

Under the New Deal administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt of the 1930s and early 1940s, tribes across the United States were given increased self-determination rights and a chance to reorganize themselves with a constitution and by-laws patterned after the national constitution. Other important components of the IRA included measures to conserve and develop Indian lands and resources as well as the right to form businesses and other organizations. Tribes were given the choice of rejecting or accepting the IRA. While many tribes accepted the act and developed constitutions, Navajos rejected it, largely because they believed that it would lead to increased livestock reduction. Older Navajos still remember that vote.

In truth, livestock reduction had begun as far back as 1928, when it became apparent that there was more livestock than the land could support. Since their release from Fort Sumner Navajos had endeavored to increase their herds so as to become self-sufficient and self-sustaining. By the 1920s, however, they had become so successful that government officials felt that the land was not able to support the growing numbers of livestock. Overgrazing and soil erosion had increased as the years went by, often leading to serious land deterioration.

The resulting government-mandated livestock reduction had a traumatic economic and psychological effect on the Navajo Indians. It was particularly devastating to those whose total reliance was on their livestock, which included the majority of the Navajo people. Grazing regulations were developed and enforced. Range management districts were created. John Collier took a leading role in the stock reduction as Commissioner of Indian Affairs, and even today his name is disliked among older Navajos.

Although Navajos had rejected the IRA thinking that its defeat would save them from enforced stock reduction, such was not the case. Stock reduction began in earnest in 1934 and continued throughout the decade. Government officials came on to the reservation and began to shoot sheep and horses, often right at their owner’s homes. Carcasses reportedly were left to rot. The animals that Navajos had prayed for since returning from Fort Sumner were now being systematically destroyed by government agents, often without the owners understanding the reason.

Indian traders were able to buy some Navajo livestock at rock-bottom prices and keep grazing them on the reservation, creating great resentment. There was little or no understanding of the strong emotional attachment that Navajos had to their livestock, especially the sheep. Navajos say dibe bee iina, “sheep is life.” Without sheep, people no longer had a dependable means of support and could barely sustain themselves.

Clara Maryboy remembered the stock reduction period as a time when her family was forced to take their sheep from the San Juan River grazing area south to Mexican Water. She told how every night sheep were butchered and eaten. When they reached Mexican Water, the sheep had to be sold to the trader.21 With much of their basic means of survival stripped away, people returned home with great discouragement. Thousands of sheep were sold or destroyed at this time and many families never fully recovered. For families with small herds, even a small percentage of animals lost was difficult. More wealthy Navajos, those called Ricos, some with sheep herds numbering in the thousands, were also impacted but managed to survive.

While Navajos were undergoing reduction of their livestock herds, their leaders were also hearing of events going on around the world that would culminate in World War II. The Navajo Nation Tribal Council passed a resolution in 1940 supporting the U.S. government, which read in part:

Whereas, it has become common practice to attempt national destruction through the sowing of seeds of treachery among minority groups, such as ours, and

Whereas, we hereby serve notice that any un-American movement among our people will be resented and dealt with severely, and

Now, Therefore be it resolved that the Navajo Indians stand ready as they did in 1918 to aid and defend our government and its institutions against all subversive and armed conflict and pledge our loyalty to the system which recognizes minority rights and a way of life that has placed us among the greatest people of our race.22

In December 1941 Pearl Harbor was bombed by Japanese forces and the United States went to war against Germany, Italy, and Japan. This had a great impact on Navajo people, as many Navajos entered the military to fight for the United States. Several thousand Navajos left the reservation for the first time to work in industries related to war efforts at places such as Fort Wingate, New Mexico, and Bellemont, Arizona. This provided an impetus for a major transition from a trade to a cash economy.

Navajo “Code Talkers” played a major part in winning the war against Japan. Hundreds of Navajos were recruited by the Marines and trained to be Code Talkers. They developed a code based on the Navajo language that was used in the Pacific War Theatre. The code proved impossible for the Japanese to break. For the first time, messages sent could be secure and not intercepted. Navajo Code Talkers played a highly significant role in the winning of the war. “Were it not for the Navajos, the Marines would never have taken Iwo Jima…The entire operation was directed by Navajo code,” reported Major Howard M. Conner.23 The efforts of the Code Talkers were top secret and did not appear publicly in print until the late 1960s, more than twenty-five years later. Even today, some Indian veterans are reluctant to discuss their service in the war effort.

Many other Navajos served in World War II besides the Code Talkers. Indian soldiers participated in some of the most famous battles of the war, including those at Guadalcanal, Bougainville, Iwo Jima, Saipan, and Okinawa. Some 3,600 of them served in the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and even in the Women’s Army Corps, and in virtually every theatre of operation.

Following tradition, Navajos were blessed at protection ceremonies before they went overseas. Maurice Knee described his ceremony, which was typical of many ceremonies held for the servicemen: “It was the Going to War ceremony. The blessing that they gave me was supposed to put a shield around me, an invisible shield, that the bullet would come right for my nose and hit that shield and go away. And it worked. I came back. If it hadn’t worked I wouldn’t be here!”24

Seth Bigman, a Utah Navajo, served in the Pacific with the U.S. Navy for almost three years. He reported that it was a good experience, but was a major change from the dry land to a floor of water. He said that he didn’t have any difficulty since he had been among white people a lot. When he came back from war his old hataalii, his medicine man, told him:

The mother has send out her child to go on the warpath…the same way as Mother Earth sent out her warriors to defend her. The rainbow is the defense of Mother Earth, where the land and water meet…When you go through the rainbow to war, that’s the defense of Mother Earth…

The medicine man prayed for me when I’m going over and coming back. I was back three times on leave…He prayed that I’ll be coming home safe, come back through that rainbow. So I did, I came home safe.25

In 1946, shortly after the end of the war, Congress established the Indian Claims Commission, authorizing tribes to file claims against the U.S. government for lands taken without just compensation. Among the claims was the traditional homeland of the Navajo people, Dinetah. It took more than twenty years to settle many of these claims, and some are not settled yet. In order to receive monetary compensation for lost land, native people had to give up all their rights to an area.

Utah Navajos became more knowledgeable about the justice system. Some residents of southeastern Utah were trying to claim Navajo lands under provisions of the Taylor Grazing Act. The State of Utah also passed a statute during this time, giving ranchers the right to dispose of any horses they claimed were abandoned. Navajos tell stories of hundreds of their horses being rounded up and sold for dog food. One story in particular mentions a round-up of over 100 horses by government agents, including charges of cruelty to the animals. Utah Navajos took this case to court and were awarded $100,000; reportedly it was the first time American Indians had successfully sued the government for intentional wrongdoing.

A group of Navajo horsemen

In 1956 Congress authorized the construction of Glen Canyon Dam, which created Lake Powell. Hundreds of Navajos were relocated from canyons on the south sides of the San Juan and Colorado Rivers. The land exchange was authorized by the Navajo Nation and the federal government–about 53,000 acres of soon-to-be-flooded reservation land was traded for public domain land on McCracken Mesa, northwest of Aneth, Utah. Little has been written about this forced relocation. The land on which the people were to be relocated was already occupied by other Navajos, whose wishes were not considered. The exchange was finalized in 1959. Some Navajos such as Jack Jones, a descendent of K’aayellii, tried to reclaim their aboriginal land rights. Although these claims reportedly were well documented, they were denied by the Department of the Interior. The Utah K’aayellii descendents requested funds to purchase additional grazing rights in 1961 but the request was denied by the courts.

In 1961 Hosteen Sakezzie and Thomas Billy sued the Utah Indian Affairs Commission on behalf of all Navajos living around Aneth. The commission had spent Navajo oil royalty money on projects which, according to the plaintiffs, did not benefit Navajos. The court agreed with Sakezzie and Billy. In 1963 Hosteen Sakezzie again sued the Utah Indian Affairs Commission for not complying with the earlier court order. He accused the commission of refusing to consult with Navajos, refusing to give Navajos information on its spending activities, and spending large sums of money on projects that did not benefit the Aneth Navajos. Again the judge ordered the commission to comply with the court orders and spend the money on projects that would benefit the Aneth Navajos.