John S. McCormick, Utah History Encyclopedia, 1994

Zion’s Bank Notice

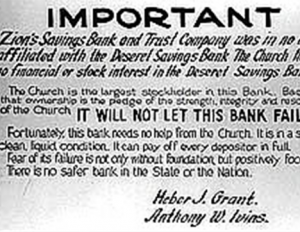

Utah was among the states hit hardest by the Great Depression of the 1930s. That claim surprises many people, who assume, for various reasons, that it was spared the worst. A few statistics make the point. In 1933 Utah’s unemployment rate was 35.8 percent, the fourth highest in the nation, and for the decade as a whole it averaged 26 percent. By 1932 the wage level for those who had not lost their jobs had declined by 45 percent and the work week by 20 percent. Annual per capita income dropped 50 percent by 1932, and in 1940 had risen to only 82 percent of the pre-depression level. By the spring of 1933, 32 percent of the population was receiving all or part of their food, clothing, shelter, and other necessities from government relief funds: 32 of Utah’s 105 banks had failed; and corporate business failures had increased by 20 percent.

During the two-year period after the Utah Division of Employment Security began operating in 1938, one of every three Utahns was employed long enough to receive unemployment compensation. Nearly 60 percent of them exhausted their benefits before finding another job. Of those placed in jobs, only one quarter were in permanent positions; the rest were either in temporary government programs or in private jobs lasting less than 30 days. To some, the solution seemed to be a return to the farm, but the economic dry rot of the 1930s afflicted the countryside as well as the cities. Between 1929 and 1933 Utah’s gross farm income fell nearly 60 percent. Season after season individual farmers suffered from the miserably low prices they received for their products, and it made little difference what they grew or raised; they considered themselves lucky to sell their products for enough to meet their costs of production.

In the early years of the Depression public officials professed to be confident that it would be short. According to Salt Lake City Mayor, John Bowman in 1931, the hard times would soon pass “and merge into a period of unprecedented prosperity.” Instead the situation only got worse. Long lines of hungry men and women, their shoulders hunched against cold winds, edged along sidewalks to get a bowl of broth from private charity soup kitchens or city-operated shelters, often nicknamed, as in Park City, “Hoover Cafes.” Shoeshine “boys” abounded on city sidewalks, ranging in age from teenagers who should have been in school to men past retirement age. Since selling on commission was one job easily available even during the hardest of times, an army of new salespeople appeared on the street peddling everything imaginable—from paper drinking cups to cheap neckties.

As in the nation as a whole, Utah’s marriage rate dropped as did the birth rate. The divorce rate rose. More and more women joined the work force, even though the feeling was widespread that when jobs were scarce, women ought not to compete with men for them. Most school districts would not hire married women and stipulated that when single female teachers married they had to resign. In 1932 a bill was introduced into the State Legislature requiring all married female state employees to submit their resignations. Those women who stayed at home followed the old adage, “Use it up, wear it out, make it do, or do without.” That meant practicing endless little economies, such as buying day-old bread, relining coats with old blankets, saving string, old rags, and wire in case they might come in handy some day, shopping creatively, and watching every penny. More than that it meant constant anxiety for fear some catastrophe, large or small, might completely swamp the family budget.

Transients were more and more in evidence. On 26 November 1930, according to the Deseret News, “More than 500 men who came to Salt Lake City looking for work from other sections of the country have been picked up during the last three days by members of the police department and sent on their way.” Unable to pay rent or meet mortgage payments, many families were dispossessed from their homes. In the summer of 1933 the Deseret News reported hundreds of homeless families were camped out on vacant lots throughout the city.

Increasingly, evictions proceeded only over citizen protest. On the afternoon of 23 February 1933 Salt Lake County Sheriff Grant Young and several of his deputies were scheduled to conduct a tax sale from the west steps of the City and County Building. Six houses and a farm were to be sold for back taxes following mortgage foreclosures. A crowd of several hundred people gathered to try to prevent the sale. Sheriff Young appealed to them to disperse; instead, they stormed the building. Deputies turned a fire hose on them, slowing them only momentarily, and they quickly wrestled the hose from the deputies and turned it into the building, flooding the ground floor. Police finally succeeded in dispersing the crowd with tear gas and arrested seven men and a woman for “direct rioting.” Eventually, fifteen people were arrested, found guilty, fined and sentenced to brief jail terms. Next day, the Salt Lake Tribune‘s account of the event featured one photograph of the crowd gathered on the City and County Building grounds and another showing clouds of tear gas billowing from it. That afternoon the Deseret News ran an editorial expressing sympathy for people who were losing their homes but characterized leaders of the crowd as “out and out communists.”

In addition to tax protests, at least half a dozen demonstrations were held in Salt Lake City during the early years of the Depression. Typical were three in the Spring of 1931 when groups of more than one thousand unemployed men and women gathered on the grounds of the City and County building to hear speakers and then marched up Main Street to the State Capitol, carrying signs that read, “We Want Work, Not Charity,” “Organize or Starve,” and “We Want Milk for Our Children.” Following more speeches at the Capitol, they met with legislative leaders and presented them with a list of demands, including a moratorium on mortgage foreclosures, a free school lunch program, unemployment compensation, the establishment of free, state-operated employment bureaus, and thirty hours work for forty hours pay. The marches had been organized by a variety of groups, including the Unemployed Council, the Worker’s and Farmer’s Protective Union, the Working People’s League, the Worker’s Ex-Servicemen’s League, the People’s Open Forum, and the Worker’s Fund. Some of these groups were organized on a national level and had Utah affiliates; others were local Utah groups only.

As was the case throughout the nation, people in Utah at first relied on voluntary charitable activities and local government to bring relief. Such efforts were ingenious and wide-ranging. Chambers of Commerce throughout the state canvassed cities and towns block by block to identify people in need. The American Legion undertook a Job Canvas Program. Fraternal organizations held rabbit hunts and donated the thousands of rabbits killed to the needy. School teachers, private businesses, and hospitals held fund raising events. High schools donated the proceeds of basketball games to the poor. Movie theaters regularly donated their days’ receipts. Community Fast Days were held, and people contributed money they would otherwise have spent for meals.

In 1930 Salt Lake City set up a relief committee and other cities and towns followed suit. It established a free city employment bureau and undertook a number of work projects financed by city money and private contributions, including construction of the Art Barn and buildings at the Salt Lake City Zoo and in Memory Grove. A free school lunch program was established. Vegetable seeds were distributed free of charge and city land was made available for gardens. By March 1932 the City had spent more than $450,000, but only $302 remained, and there was little prospect of raising more money.

Finally Utah, like the rest of the nation, turned to the federal government for help. The problems of industrial capitalism had proven too heavy for individuals, private charities, or local governments to handle. Washington responded with a barrage of programs that came to be known as the New Deal. Because the depression hit Utah so hard, New Deal programs were extensive here. Per capita federal spending in Utah during the 1930s was ninth among the forty-eight states, the percentage of Utah workers on federal relief projects was far above the national average, and for every dollar Utahns sent to the nation’s capital in taxes, the government sent back seven dollars through various programs.

The range of New Deal programs here was broad. A school lunch program was established, and free classes in nutrition were offered. Adult education programs and summer recreation programs for children were set up. Thousands of miles of highways, roads, sidewalks, and sewer systems were constructed. More than 250 public buildings of all kinds were built under federal programs: city halls, county courthouses, schools, college and university buildings, fire stations, and national guard armories. About half of them are still standing, dramatic evidence of the impact of the New Deal in Utah.

The Works Progress Administration (WPA) alone employed an average of 12,000 people annually between 1935 and 1942, with a peak of 17,000 in 1936. A 1939 survey revealed that Utah’s average WPA worker was thirty-eight years old, married, with two to three children. The WPA Art Project was responsible for the creation of thousands of works of art, including the paintings of historic Utah figures and events in the State Capitol dome. The Utah Symphony Orchestra started as a WPA Music Project. The Federal Writer’s Project sponsored the collecting, cataloging, and publication of historical documents, employing such people as Juanita Brooks and Dale Morgan. Following several steps behind federal programs, the Mormon church in 1936 established what later came to be known as the Church Welfare Plan. Primarily a direct relief program providing commodities and supplies along with work, its effect was substantial, but it only supplemented governmental action. Federal non-repayable expenditures in Utah for the period 1936–1940 were ten times as great as the accountable value of church-wide Welfare Plan transactions.

The Depression years also saw a reinvigoration of Utah’s labor movement, beginning in 1933 when coal miners, after a thirty year effort, were finally unionized. Success in the coal fields stimulated efforts in other areas, and by 1937 union membership in Utah had increased six fold. The 1930s also brought political changes. The Republican Party, which had dominated Utah politics since statehood in 1896, fell from favor, and from the early 1930s until the late 1940s the Democrats dominated Utah politics as thoroughly as had the Republicans previously. Although the scope of the New Deal was immense, it did not end the Depression in Utah or the rest of the nation. World War II did that. During the War years Utah reached full employment for the first time in the twentieth century. Worker’s incomes increased by fifty percent; corporate profits doubled. By the time the war ended, Utah, like the United States as a whole, had never been so prosperous.

See: Leonard J. Arrington, Utah, the New Deal and the Depression of the 1930s. Ogden, Utah: Weber State College, 1982; John F. Bluth and Wayne K. Hinton, “The Great Depression,” Chapter 26 in Richard D. Poll, et al., eds. Utah’s History, Provo: Brigham Young University Press, 1978, and John S. McCormick, “Hard Times,” Chapter VIII in Salt Lake City, the Gathering Place. Woodland Hills, California: Windsor Publications, Inc., 1980.