Matthew Despain and Fred R. Gowans

Matthew Despain and Fred R. Gowans

Utah History Encyclopedia, 1994

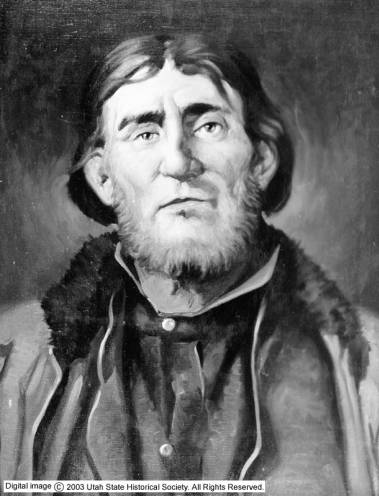

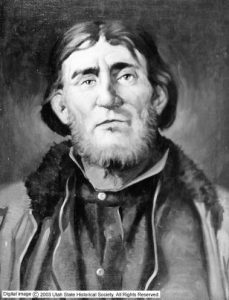

James Bridger was one of the greatest frontiersmen of Utah and American history. During his lifetime he was a hunter, trapper, trader, Indian fighter, and guide, and one of only a few trappers to remain in the Rockies after the demise of the fur trade. In 1822 young Bridger heeded William Ashley’s call for one hundred “enterprising young men” and ascended the route of the Missouri River under Major Andrew Henry’s command.

Bridger spent his first year with the company on the upper Missouri until Blackfoot Indian hostilities forced the expedition back down river in the spring of 1823. Bridger then accompanied Henry’s brigade to the Yellowstone River, where, en route, Hugh Glass was attacked by a grizzly. Evidence would indicate that Bridger volunteered as one of Glass’s caretakers, but that he abandoned Glass believing he would not live. Glass miraculously survived and apparently exonerated Bridger’s desertion due to his youth.

Bridger spent the fall of 1823 and the following winter and spring of 1824 trapping and wintering in the Bighorn region as part of John Weber’s brigade. By summer’s end, he had pushed west across South Pass to trap the Bear River. The brigade assembled in “Willow Valley” (Cache Valley) to winter on Cub Creek near present Cove, Utah. Allegedly during that winter of 1824-25 a dispute arose concerning the Bear River’s course south of Cache Valley. Bridger was selected to explore the river to resolve the question. His journey took him to the Great Salt Lake, which he believed was an arm of the Pacific Ocean due to its saltiness. For years, Bridger was recognized as the first documented discoverer of the great “Inland Sea”; however, more recent evidence seems to indicate that this honor should be given to Etienne Provost.

The following spring, Weber’s brigade spread along the Wasatch Front to trap. In May, Bridger was probably at the Ogden-Gardner trappers’ confrontation near present Mountain Green; however, there is no documentation that indicates he participated in the proceedings. That summer Bridger attended the Randavouze Creek rendezvous, just north of the Utah-Wyoming border near the present town of McKinnon, Wyoming.

The winter of 1825-1826 was spent by Bridger and most of Ashley’s men in the Salt Lake Valley in two camps: one at the mouth of the Weber River and one on the Bear. Bridger continued to trap the regions of the Wasatch Front for approximately the next four years, spending some of his winters in the Salt Lake Valley. He was present at all the rendezvous, including the Cache Valley rendezvous of 1826 and the rendezvous of 1827 and 1828 on the south shore of Bear Lake at present-day Laketown, Utah.

In 1830 Bridger and four other partners formed the Rocky Mountain Fur Company; however, exhausted fur reserves and increased competition from John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company forced the company to venture north into hostile Blackfoot territory. The Rocky Mountain Fur Company was dissolved in 1834 and by the end of the decade the fur trade itself was over.

During the final years of the fur trade, Bridger, with partner Louis Vasquez, planned and constructed what was to be Fort Bridger, located on Black’s Fork of the Green River. This new enterprise was to become one of the principal trading posts for the western migration, established specifically to serve the wagon trains heading to the far West. Bridger’s post served many immigrants heading west, including the ill-fated Donner-Reed party.

In June 1847 Bridger had his first encounter with the Mormon pioneers near the mouth of the Little Sandy River. At this gathering, Bridger and Brigham Young discussed the merits of settling in the Salt Lake Valley. Also during this meeting Bridger drew his map on the ground for Young depicting the region with great accuracy and conveyed to the Mormon leader his misgivings regarding the agricultural productivity of the Salt Lake area. This first meeting between the Mormons and Bridger appears to have been pleasant, yet this relationship was to become a bittersweet one for Bridger.

The coming of the Mormons increased the number of immigrants at the fort. However, the Mormon settlements attracted away a significant portion of Bridger’s trade, including that of the Indians, causing economic hardships for the post.

In 1850 Bridger consulted and guided the Stansbury expedition, which established a road much of which would later become the route of the Overland Stage and the Union Pacific Railroad. The same year, the territory of Utah was created; it included under its jurisdiction the Fort Bridger area.

Animosity between Bridger and the Mormons festered in the summer of 1853. Mormon leaders were convinced that Bridger was engaged in illicit trade with the Indians, especially guns and ammunition, and that he had stirred hostility among the Native Americans against the Mormons. Mormon leaders revoked Bridger’s license to trade and issued a warrant for his arrest; however, before the posse’s arrival Bridger had fled.

By the end of 1853, the Mormons had begun to move in and secure control of Bridger’s Green River Basin, opting to establish Fort Supply rather than occupy Fort Bridger. Bridger had gone to the east, but returned to the mountains in 1855. That summer, Bridger sold his fort to the Mormons for $8,000. The Mormons paid Bridger $4,000 in gold coin that August; however, the final payment was not made until 1858, when Vasquez received the remaining $4,000 in Salt Lake City.

The Mormons took possession of Fort Bridger in 1855, making much-needed improvements, including erecting a large cobblestone wall around the fort. However, in 1857, the fort was destroyed by the Mormons to hinder the advance of Albert Sidney Johnston’s Army, which was being guided by none other than James Bridger. The army occupied the fort until 1890. Bridger tried to deal with the army regarding leasing the fort under the premise that the Mormons had forced him out and stolen it from him. During the 1870s and early 1880s, Bridger inquired about the army’s lease, but without success.

Bridger died in July 1881. After his death, the government paid his widow for the improvements of the post, which consisted of thirteen log structures and the eighteen-foot-high cobblestone wall, which, ironically, were built by the Mormons.

See: Cecil J. Alter, Jim Bridger: A Historical Narrative (1986); Fred R. Gowans and Eugene E. Campbell, Fort Bridger, Island in the Wilderness (1975); LeRoy R. Hafen and Harvey L. Carter, eds., Mountain Men and Fur Traders of the Far West (1982); and Dale L. Morgan, ed., The West of William H. Ashley (1964).