Ronald G. Coleman

Beehive History 19

Blacks were employed almost exclusively as waiters and porters on the Union Pacific Railroad.

Much has been written about politics at the turn of the century in Utah, especially the struggle to achieve statehood. Less well known are the political activities of blacks in that era. Two dynamic and colorful leaders—one a Republican and one a Democrat—emerged within the black community in the 1890s and took active roles in local politics. Their rivalry occurred at a time when African Americans in Utah were developing the institutions and organizations that would help to define them as a community.

Sina and Wayne Banks in front of their Salt Lake City home in 1914.

Between 1890 and 1910 Utah’s African American population increased from 588 to 1,144, with the majority living in Salt Lake County. Ogden’s black population totaled 204 by 1910, but Salt Lake City continued to be the focal point of social activities and community development for black Utahns.

In Utah, as elsewhere, the first community institution established by African Americans was typically a church. It was often the center of social activities as well as a meeting place for church-sponsored auxiliaries, literary societies, and other organizations. Ministers often served as community leaders and as spokesmen for the black community. In addition to serving the spiritual and secular needs of local African Americans, the church, along with fraternal organizations and newspapers, provided an important link with the national black community.

The Trinity African Methodist Episcopal Church can trace its beginnings to an organizational meeting held in November 1890 in Salt Lake City, and the Calvary Baptist Church dates from the mid-1890s. The establishment of churches was followed by fraternal orders and civic and social clubs, including Masonic lodges, women’s organizations, and the Booker T. Washington Literary Club.

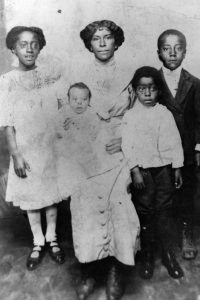

Martha Ann J. Stevens Perkins and family, Granddaughter of Green and Martha Crosby Flake.

The existence of these groups provided black Utahns with a base from which their social activities evolved. Observances in honor of the Emancipation Proclamation were held regularly between 1890 and 1910. The 1897 celebration was unusually large as black civilians and soldiers of the 24th Infantry combined to stage a parade with floats and the regimental band, followed by a musical program, speeches, and a grand ball. African Americans also joined the larger community celebration of the Pioneer Jubilee, with Green Flake, Jane Elizabeth James, and Sylvester James—three black pioneers of 1847—receiving special recognition.

Black newspapers were first published in Utah during the 1890s, another sign that the African American community was developing along national lines. Two newspapers and the men who published them are of special interest in helping to define the political objectives of blacks in Utah at the turn of the century.

The Utah Plain Dealer was published by William W. Taylor from about 1895 to 1909. Its chief competitor was the Broad Ax, published by Julius Taylor (no relation) from 1895 to 1899. Black newspapers reflected the ideas and political affiliations of their owners; however, like black newspapers throughout the nation the black press in Utah defended the rights of African Americans and constantly reported injustices at both the local and national levels.

In the pages of their newspapers William Taylor and Julius Taylor continually argued over which publication truly represented the interests of African Americans. William Taylor supported the Republican party, and Julius Taylor supported the Democratic party.

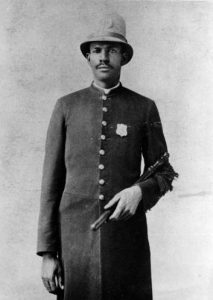

Detective Paul Cephas Howell served on the police force from 1907–1912.

The two Taylors did not have the journalistic field to themselves. Other black newspapers published in Utah between 1890 and 1910 include the Western Recorder owned by S. P. Chambers, the Headlight published by J. Gordon McPherson, Town Talk with W. P. Hough as editor, and the Tri-City Oracle published by Rev. J. W. Washington. The editors of Utah’s black newspapers participated in professional journalistic organizations. Both Taylors were members of the Utah Press Association, and Julius served as historian of the organization before moving to Chicago in 1899. Utah’s black publishers took an active part in the Western Negro Press Association. They presented papers at meetings, served as officers, and hosted the WNPA’s fifth annual meeting in Salt Lake City in 1900.

Julius Taylor presented a paper on lynching at the 1898 WNPA meeting. He claimed that a resolution condemning lynching was made part of the 1896 Republican Platform only to give the appearance of Republican support for black rights and to overshadow the discrimination against black delegates to the GOP convention at St. Louis hotels. Furthermore, he asserted, since Republicans were not willing to act beyond their public utterances they should not use lynching as a political issue.

In 1899 William Taylor was elected president of the WNPA, and when the organization’s 1900 convention was held in Salt Lake City black residents hosted receptions for the participants and took their guests on tours of the city.

Black Utahns took an interest in politics and, like the majority of African Americans, tended to be Republicans. Many of the political activities of black Utahns were orchestrated by the Abraham Lincoln Colored Club, a black Republican organization. In 1895 a challenge to Republican dominance among blacks emerged under the leadership of Julius F. Taylor. Taylor, who had lived in Fargo, North Dakota, and Chicago, moved to Salt Lake City with his wife in the spring of 1895 because of her health. That fall Julius began publishing the Broad Ax and espousing the Democratic party’s cause. An active Democrat for more than 10 years, Taylor called upon blacks to no longer follow the GOP because of past prejudices or emotions. He reasoned that African American voters would see that on the issues of the day the Democrats were entitled to as much, if not more, support from black voters. His involvement in Democratic politics led him to visit various towns throughout the state where he ingratiated himself with party leaders. His actions alarmed black Republican leaders, and an effort was made to discredit him as a carpetbagger.

The emergence of support among blacks for the Democratic party, although light in actual numbers, set into motion a political feud that continued into the 20th century. Julius and William Taylor used their rival newspapers to trade insults—all in the name of politics—that would be labeled libelous today.

William Taylor came from St. Louis and had settled in Utah in 1890. A major influence in Utah’s early black community, he led the A.M.E. church when it was without a minister, served as exalted ruler of the Masonic lodge, and was an active leader among black Republicans. His prominence within the black community presumably led to his appointment as city dog tax collector during 1894–96, the only political patronage post secured by an African American in this period. Surprisingly, he was appointed by a Democrat. The general lack of political patronage for blacks who supported the Republican cause brought criticism not only from black Democrats but from black Republicans as well.

When a predominantly Democratic legislature took office in January 1897 Julius Taylor offered himself as a candidate for the position of sergeant-at-arms for the State Senate on the basis of his work in the party’s behalf and as recognition of “the colored race.” He had some reason to believe he might win the post. During the first state legislative session in 1896 the Democrats, then a minority, had voted for Taylor to be messenger of the Senate and endorsed Henry Durham, also an African American, for sergeant-at-arms, aware, of course, that the Republican majority would actually fill those posts. A year later the Democratic majority rejected Taylor. He reported in the Broad Ax that the legislators “have informed the world that they do not entertain a very high regard for any member of the Negro race.”

At election time black Democrats and Republicans staged political debates to appeal for the votes of African Americans. In October 1895 Henry Durham, the former vice-president of the Abraham Lincoln Colored Club, now a Democrat, challenged Cyrus Lindell, a Republican, to a debate. The event received coverage in the white as well as the black press. The subject of the debate was “that it is more beneficial to the Negroes of the United States to vote the Democratic ticket than the Republican ticket.” Durham took the affirmative and Lindell the negative. White leaders from the respective parties—George M. Cannon, Republican, and Judge Orlando W. Powers, Democrat, served as seconds. The debate quickly digressed into a discussion of which party had done the most for African Americans during the Civil War.

In a further effort to attract voters black leaders sponsored social events. On November 1, 1895, the Broad Ax offered an evening of music and dancing. An address by Julius Taylor entitled “The New Democracy” preceded the festivities. The Republican city committee aided black Republicans in sponsoring and evening of entertainment. William Taylor introduced white GOP leaders who spoke on the benefits of voting for the Republican ticket. The speeches were followed by dancing.

The solid support the Republican party had once received from African Americans was weakening. This may have influenced the Salt Lake County GOP organization to nominate William Taylor as the Republican candidate for the Eighth District seat in the Utah House of Representatives. His nomination was the first for an African American in Utah. Taylor supported the platform adopted at the Salt Lake County Republican convention.

Underscoring the black community’s political diversity, the Broad Ax opposed William Taylor’s candidacy. The Democratic newspaper claimed that he was unqualified to serve and that he did not represent the blacks of Utah. He retaliated by using his position as exalted ruler of the High Marine Masonic Lodge in Salt Lake City to purge men who had abandoned the Republican party. The purged Masons responded by requesting, through the military lodge at Fort Duchesne, a special dispensation to open a lodge affiliating with the Missouri Grand Lodge. Their request was granted, and the Saint Mark’s Lodge was established on August 20, 1897.

Although William Taylor received fewer votes than any other candidate in the Eighth District, his 6,542 total was nevertheless impressive. It shows that several thousand whites were willing to cast their ballots for an African American.

By 1910 a black community centered in Salt Lake City had emerged in Utah. In response to their general exclusion from full participation in Utah’s social and cultural activities, they established their own churches, fraternal organizations, newspapers, and political and social groups. Like African Americans elsewhere they created and supported those institutions that gave greater meaning to their lives. In this manner black Utahns embraced the spirit of race consciousness and self-help commonly associated with the national black community during the “Age of Booker T. Washington.”