W. Paul Reeve

History Blazer, April 1995

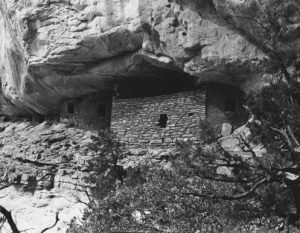

Three Fingers Ruin, Hammond Canyon

The elaborate cliff dwellings and terraced apartment houses built of stone, mud, and wood that dot the Four Corners region of southeastern Utah stand as fitting monuments to Utah’s earliest inhabitants. Evidence of hunter-gatherer bands occupying portions of present-day Utah date back to about 9,000 B.C., but the people who comprised this Desert Culture did not begin to settle into a sedentary agricultural lifestyle until around A.D. 400. It was during what archaeologists term the Pueblo Period (c. A.D. 500-1300) that Utah’s early peoples reached their peak of development and produced a cultural flowering.

The key to this flourishing, and the resulting new way of life, was agriculture. The Anasazi (a Navajo word meaning “the ancient ones”) of Utah were largely centered in the San Juan drainage basin and likely received corn and squash and the knowledge to raise them from their southern neighbors in Mexico. Domesticated plants offered a reliable food source that made an increase in population possible and also freed time for other activities such as religion, art, ritual, public works, and handicrafts. The Anasazi were also able to settle into a sedentary lifestyle; their first dwellings, or pit houses, generally contained central fireplaces and were often made of horizontal logs laid with mud mortar. The basket-making techniques of the Desert Culture evolved and began to include complicated color designs worked into the baskets. Anasazis also wove beautiful bags from vegetable fibers for storage and carrying supplies and created brightly colored sandals with exquisite craftsmanship.

Anasazi society continued to evolve and progress. During A.D. 500-700 they began to build circular pit houses of stone slabs with wooden roofs and grouped them in larger organized communities. The ancient ones also possessed beans, a prime source of protein, and new varieties of corn. Other innovations included the bow and arrow, clay pottery, turquoise jewelry, and crude clay figurines. By around A.D. 1050 the potter’s art was highly developed with a variety of decorative styles, black paint on a white base being the most common. Cotton was introduced from the south, and blankets woven on looms from this fiber replaced the earlier fur robes. Above-ground houses made of stone with mud mortar became popular, and the old pit houses evolved into kivas or sacred rooms where Anasazi men performed a variety of religious ceremonies.

The cultural climax of the Anasazi came during A.D. 1050-1300. These early Utah inhabitants skillfully built cliff dwellings and apartment houses, some of which reached five stories in height and contained hundreds of rooms. A Pueblo house of this period might include such niceties as corrugated cooking and storage pots, decorated ladles, mugs, and bowls, necklaces, pendants, flint knives, feather robes, and belts or girdles. In addition, their irrigation efforts included dikes, dams, and terraces and ingenious methods of saving water. Even these techniques, however, proved ineffective against the terrible drought conditions that began in 1276 and persisted for several years. Thousands of Pueblo people likely died, and the rest abandoned their settlements and migrated south. Hostile nomadic incursions could have also contributed to this migration, but, whatever the reason, by 1300 the complex and highly developed culture of the Anasazi had disappeared from Utah. Fortunately, they left behind stunning evidence of their hard work and industry as testaments to their once proud society.

See Jesse D. Jennings, “Early Man in Utah,” Utah Historical Quarterly 28 (1960): 3-27; Frank Waters, Book of the Hopi (New York: Viking Press, 1963); Richard D. Poll, et al., Utah’s History (Provo: Brigham Young University Press, 1978), pp. 24-25.