Robert S. McPherson

The History of San Juan County

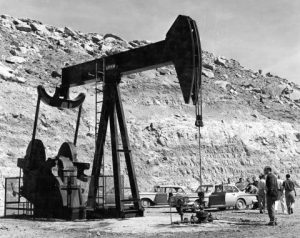

Pumping unit in White Mesa Oil Field in Aneth area

At the same time that the uranium industry in Monument Valley was booming, a second industry, oil, became increasingly prominent in the Aneth-Montezuma Creek area. Starting in 1953, Humble Oil and Shell Oil initiated agreements with the Navajo Tribe and the State of Utah to exploit the rich petroleum reserves locked beneath the Aneth lands. The Texas Company drilled its first well on 16 February 1956 and welcomed a rapid flow of 1,704 barrels per day. Other companies responded immediately; suddenly the tribe found itself administering leases and rentals throughout the northern part of the reservation, known generally as the Four Corners Oil Field.

In 1956 alone the Aneth oil field yielded $34.5 million in royalties to the tribe. With a population of more than 80,000 members, the Navajo Nation decided against making a per capita distribution of the money, which would have amounted to only $425. Instead, the leaders invested the royalties in services such as education and economic development. Much of this money, however, was used in the central part of the reservation and not on the periphery where the oil wells producing this wealth were located.When the federal government agreed to the Aneth Extension in 1933, the law that removed the land from the public domain specified that 37.5 percent of the revenues coming from oil and gas in the Extension would be used for “Navajos and such other Indians” living on this section. The money could be spent on health, education, and general welfare of the Navajos. The law expanded in 1968 to include all Navajos living on the Utah portion of the reservation.

The Utah State Legislature established a three-member Indian commission in 1959 to return royalties of $632,000 to the Navajo people. On 27 July Governor George D. Clyde attended the first meeting and charged the group to carry out the law. The commission, composed of a chairman who was a member at large, an Indian member, and a citizen from San Juan County, undertook the awesome task of helping improve living conditions across the Utah reservation, from Aneth to Navajo Mountain.

In 1968 the government amended the 1933 act to include other services to be considered general welfare; it also extended the number of beneficiaries to include all of the Navajo people in San Juan County. Road development, establishment of health clinics, economic endeavors, and education filled the agendas of the committee. Different areas had their own requirements, which became so numerous and widespread that a full-time administrative organization was needed. The Utah Navajo Development Council (UNDC) was established in 1971 with an all-Navajo board to meet the growing urgency to deliver necessary services. From a fledgling organization, UNDC expanded rapidly. Take health care, for instance. During its first fiscal year, 1971–72, Navajos totaled 8,421 visits to the two clinics located at Navajo Mountain and Montezuma Creek; by 1983 another clinic had been added at Halchita (1975) and visits had doubled to 16,845. Figures relating to education, housing, livestock assistance, and other programs show a similar rise, indicating that the organization was meeting the needs of many Utah Navajos.

By 1978, however, there was rising discontent in the oil fields. On 30 March 1978, Navajos from the Aneth-Montezuma Creek area physically took over the main Texaco pump station in Aneth and eventually stopped all production throughout the entire region. With an activist spirit common to the late 1960s and early 1970s, the group, known as the Utah Chapter of the Council for Navajo Liberation, or the Coalition, attracted more than a thousand people sympathetic to its cause. On 3 April the group listed thirteen demands that included the need to renegotiate leases, more sensitive treatment of Navajos living in the oil fields, greater environmental concern, and more benefits for those directly affected by the oil pumps in their backyard. The four oil companies—Texaco, Superior, Continental, and Phillips—that owned the 200 wells in the area, generally acquiesced to the demands, except in regard to changing the lease agreements. This settlement ended almost three weeks of occupation by Navajo protesters.Today, however, many of the problems of the Aneth oil field continue. Mobil purchased Superior’s wells, controlling those on both the north and south sides of the river in the Aneth region. Phillips and Texaco still pump oil in the Montezuma Creek area, but the Utah Navajo Development Council no longer provides services in the Utah strip. The Council and its subsidiary, Utah Navajo Industries, because of problems with mismanagement of funds, lost their economic power until legal action could be taken against those misusing the money.

Along with a diminishing number of barrels of oil and royalties, there is also diminishing enthusiasm for the oil fields among the older Navajo people, who complain of great environmental destruction. Younger Navajos often do not feel that complaint as strongly, welcoming the jobs, the royalties that pay for education and health benefits, and the other businesses attracted to the area. But, as with many other events, personalities, and technologies that have had an impact on the Aneth region, oil’s long-term effects will more truly determine whether it has been beneficial or harmful.