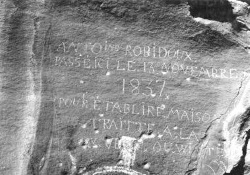

Antoine Robidoux inscription in Westwater Canyon, Utah-Colorado border

OLD ANTOINE ROBIDOUX LEFT HIS MARK IN UTAH

Becky Bartholomew

History Blazer, August 1996

Five miles west of the Utah-Colorado border, not far from I-70, Westwater Creek enters the Colorado River. A dirt road follows the creek up into the north hills. But 160 years ago some travelers chose this minor canyon as the route of least topographical resistance into the Book Cliffs. Other streams such as Sweetwater and Two Water creeks led through the Roan Cliffs to the eastern Tavaputs Plateau, then up the Green River to the rich trapping sites of the Uinta Basin.

Some distance up the Westwater Creek road, a sandstone wall about 9 feet high and 4.5 feet wide overlooks the west bank of the stream. On this wall is a prehistoric pictograph of a red shield. Above the shield is an inscription that reads:

Antoine Robidoux

passe ici le 13 Novembre

1837

pour etablire maison

traitte a la

Rv. vert ou wiyte

Translated from the French, this means: “Antoine Robidoux passed here 13 November 1837 to establish a trading post at the Green River or White.” Or, because the third letter of the word “wiyte” has deteriorated and there is an accent mark over the final “e”, the last phrase may read, “at the Green River or Winte (Uinta).” Also, “1837” may read “1831” instead.

These uncertainties have long been grist for debate among Utah historians. An accurate interpretation is important because it defines where and when Robidoux actually built his first trading post in the area. If he meant White then it was near present-day Ouray, where the White River flows into the Green. If he meant Uinta, then it may have been ten miles farther north, near Bottle Hollow Resort and the confluence of the Green and Uinta rivers.

Antoine Robidoux was born in 1794, one of five sons of Joseph Robidoux, Sr., French-Canadian owner of a St. Louis–based fur trading company. One or another of the Robidoux men are mentioned in many an explorer and immigrant journal of the 1840s and 50s.

For the Robidoux family was a prolific clan. In business with Joseph, Sr., were at least two brothers with their sons; one or more had several Indian wives. The men were not quite the cultured scions of St. Louis society that some writers have made them out to be. Most of them maintained rustic, nomadic lifestyles into old age. But they did become wealthy in the fur trade. Antoine the elder (as distinguished from a nephew Antoine) spoke English, French, and Spanish and as a young man worked for his father, helping to extend their trade farther and farther west.

By the early 1830s Antoine was developing his own trade route along the Spanish intermountain corridor between Santa Fe and the Uinta Basin. He even became a Mexican citizen to facilitate licensing and partnerships, and he built Fort Uncompahgre on the Gunnison River. Another of his posts was the Fort Uintah referred to in the Westwater inscription. Kit Carson mentioned encountering Antoine in the Uinta Basin in 1833.

The Westwater inscription reveals that, probably in 1837, instead of ascending the Tavaputs Plateau by way of western Colorado, Robidoux took an alternate route down the Colorado into the Grand Valley and north along Westwater Creek. Upon reaching the Green, speculates one historian, he commandeered Carson’s abandoned adobe fort, used it for one season and got flooded out, and then moved 20 miles north to Whiterocks where he built Fort Uintah or Fort Robidoux as it is named on some early maps. He established an almost exclusive trade with the Utes.

By 1841 Antoine, approaching age 50, began wintering in the Midwest. His speech on California delivered in Weston, Missouri, inspired John Bidwell to mount the first covered wagon expedition to the Pacific. Perhaps Antoine helped his father–then age 70–found St. Joseph in 1844. Within five years it had a population of 1,800 and for a decade was the main jumping-off point for the Oregon Trail.

In 1844 Fort Uncompahgre was destroyed by Indians, and the trapping business declined. Antoine spent the next decade as an immigrant guide and army interpreter. In 1846 he was so badly wounded in a Mexican War battle that he applied for a government pension.

Beginning in 1849-50 the Robidoux family amassed another fortune outfitting immigrants at St. Joseph and then reoutfitting them at the only blacksmith and supply station in western Nebraska. An 1851 immigrant described “an old man nearly blind” wintering at the post. This was probably Antoine, who died in 1860 in St. Louis.

Fortunately, his inscription outlived him. Unfortunately, Westwater Creek traffic has increased through oil development, and vandals have riddled the stone with bullets.

Sources: William S. Wallace, Antoine Robidoux: 1794-1860, cited in Nomination Form, National Register of Historic Places, Preservation Office, Utah Division of State History; Orral Messmore Robidoux, Memorial to the Robidoux Brothers (Kansas City, 1924), family biography cited in Merrill J. Mattes, The Great Platte River Road (Lincoln: Nebraska State Historical Society, 1969). Note: Convention is to spell it “Uinta” when describing natural features, “Uintah” when referring to man-made boundaries and entities.