By Michael W. Cater, M.D.

With the driving of the last spike of the transcontinental railroad at Promontory, Utah, on May 10, 1869, life in this western territory was forever changed. Minerals were plentiful, and mining developed into an important industry in Utah in the final decades of the nineteenth century. Yet mining was rough and dangerous work, very often associated with serious injury or death. It soon became apparent to the people of Salt Lake City that they needed a hospital. Under the inspiration and leadership of Daniel S. Tuttle, the first Episcopal Missionary Bishop to the territories of Utah, Idaho, and Montana, St. Mark’s Hospital was built to serve the local citizens and the miners who worked nearby. The first hospital in Salt Lake City—and Utah—St. Mark’s opened its doors in 1872 with a small, six-bed facility. Dr. John P. Hamilton, who recently had been the U.S. Army physician at nearby Fort Douglas, became the hospital’s first medical director. As St. Mark’s developed, it would, of course, require more staff.

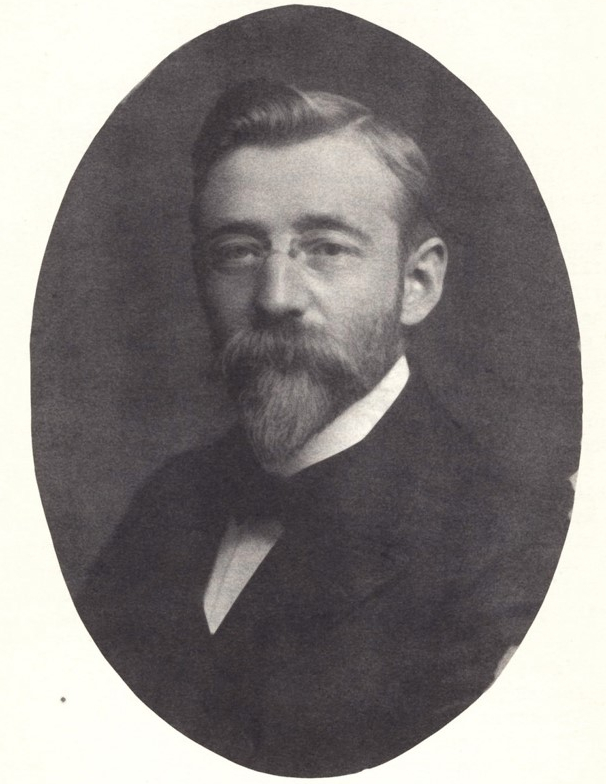

Enter Augustus Calvin Behle, a young doctor who grew up with the rigors of frontier medicine. Born to German immigrant parents in Moro, Illinois, on January 24, 1871, his father, William Henry Behle, was a Presbyterian minister who changed his calling and became a physician. After completing medical school at Keokuk Medical College, William eventually settled in Blackfoot, Idaho, in 1887. There he established his medical practice and opened a pharmacy. Augustus soon became his father’s assistant, compounder, and companion on buggy rides to visit and care for patients. Shortly thereafter, Augustus became a licensed pharmacist, perhaps partially because his father had helped establish the board of pharmacy in the county. It was here in Blackfoot that Augustus decided to follow in his father’s footsteps and become a physician. William taught him the rudiments necessary for entry into medical school, which allowed Augustus to enter Rush Medical College in Chicago without prior examination in the fall of 1891. While at Rush, he excelled as a student, especially in the surgical specialties. Augustus graduated in 1894 with honors in Obstetrics, winning the De Laskie Miller Prize for the best score on the Obstetrics final examination. The prize was a complete set of obstetrical tools in a fine wooden box.

Upon his graduation, Cook County Hospital offered Augustus Behle one of its prestigious internships. But because the house staff was unpaid at that time, he made the difficult but necessary decision to return to Blackfoot to help his father. However, shortly after returning to Idaho, the young Dr. Behle answered a newspaper advertisement for a desperately needed physician in Salt Lake City. Moving there in mid-September 1894, he joined St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, passed the Board of Medical Examiners examination October 1, and opened his first office not far from St. Mark’s Hospital. His first case was a surgical one on a Sunday morning, October 8, 1894. It was a serious hand wound necessitating sutures. The charge was $3.00, but the patient had only $2.25, which Behle accepted as full payment. Later that week, the same patient had a tooth extracted for fifty cents.

In November 1894, the medical director of St. Mark’s Hospital asked Behle if he would consider being the hospital’s first intern. Behle accepted the position only as long as he could maintain his office practice two hours a day. In 1895, Behle became a charter member of the Utah State Medical Society. As the only intern in the hospital, Behle assisted in all the surgeries performed there. In one case he showed one of the staff surgeons how to use the newly invented Murphy Button for an anastamosis (or connection) of the bowel. The hospital records for 1894 indicate that Behle assisted in operations for the removal of gall stones, amputation of the middle third of a thigh, laparotomy, strangulated hernia, nephrectomy, eye enucleation, cataract removals, mastoidectomy, and many more surgeries, both routine and complicated. In addition he cared for all the medical patients, mainly those with various infections (particularly typhoid fever) and with plumbism—the lead poisoning that was a common complication of mining. As if this were not enough, Behle also served as the hospital pharmacist and was responsible for compounding all the prescriptions used in the hospital. Furthermore, Behle assisted other staff physicians when surgery was performed in a patient’s home. In these cases he was responsible for administering ether anesthesia.

Behle’s recent education benefited the hospital in other ways, as well. When he arrived at St. Mark’s, the institution did not have a microscope. Working through one of his classmates at Rush, who was doing postgraduate work in Hungary, Behle arranged to have a fine microscope delivered to St. Mark’s.

After Behle had worked for three years as the hospital intern, Dr. S. J. Pinkerton, a fellow surgeon on the St. Mark’s medical staff, encouraged him to pursue postgraduate studies at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. Having previously met Dr. William H. Welch, one of the founding professors of Johns Hopkins, Pinkerton provided Behle with a letter of introduction and some much-needed funding for the year-long course. Behle spent the 1897–1898 academic year at the Johns Hopkins Hospital as a special research assistant in the pathological laboratory. While there, Behle polished his histological skills, which included making his own tissue slides, a practice he would continue throughout his long career.

While at Hopkins, Behle had the opportunity to work with many of the outstanding physicians on the staff, including doctors Osler, Welch, Kelly, Halstead, Finney, Cushing, and Flexner. According to Behle’s son, Osler—considered by many to be the greatest physician of his time and its most famous medical historian—would hum tunes as he made rounds and would throw his arm around Behle, saying “how many wives have you got back in Utah?”

The remarkable physicians at Hopkins all impressed Behle, yet the one who had the greatest influence on him was Welch. He was the “master of masters” in pathology and bacteriology, and he vigorously promoted the cause of aseptic surgery. Upon completion of Behle’s year of study at Hopkins, Welch recommended him for the position of pathologist at the Lakeside Hospital in Cleveland. Had it not been for Pinkerton’s strong persuasion, Behle would have taken the position at Lakeside Hospital and not returned to Salt Lake City.

On his return to Utah, St. Mark’s Hospital appointed Behle as the staff surgeon and hospital pathologist. At Pinkerton’s request, Behle was asked to bring St. Mark’s operating room up to Hopkins’s standards. Out with the carbolic acid, wooden buckets, and wooden operating tables and in with a new sterilizer, stainless steel operating tables, rubber gloves, the five-minute scrub, face masks, and the sterilization of sutures. Indeed, Behle was the father of asepsis in Utah and the West.

In 1903, Behle embarked on the first of several trips to medical centers in Europe and the United States. He first stopped in Rochester, Minnesota, where he watched the Mayo brothers operate. While making rounds with Charles Mayo, Behle happened upon an old friend from Rush, Dr. Edward H. Ochsner, who was a patient at Saint Marys Hospital. Ochsner recommended that he study in Vienna and arranged quarters for Behle to use upon his arrival there.

While in Vienna, Behle worked at the famous Allgemaines Krankenhaus under the tutelage of many of the world’s leading physicians, including professors Anton Weichselbaum (pathology), Anton von Eiselsberg (surgery), Friedrich Schauta (gynecology), Wagoner (neurology), Schlessinger, Nothnagel, Kovacs (internal medicine), Czerney (orthopedics), Turk (blood diseases), and Arthur Biedle. During his stay in Vienna, Behle helped establish the American Medical Association of Vienna. Leaving Vienna, Dr. Behle continued to travel throughout Europe to observe and study with other great medical personalities including the physicist Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen, Theodor Kocher, Jan Mikulicz-Radecki, Ernst Sauerbruch, and August Bier.

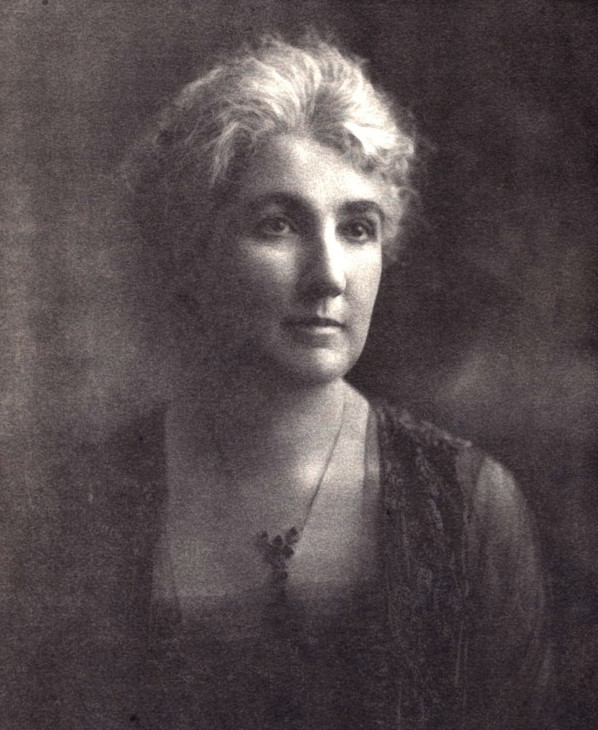

On returning to Utah, Behle met Daisy May Harroun, one of the three graduates of the St. Mark’s School of Nursing in 1898. The couple’s wedding took place on May 15, 1905; Behl was thirty-four years old at the time. In the upcoming years, he worked to refine and teach his surgical skills to surgeons in Salt Lake City. In 1906 he was appointed to be a special lecturer at the newly founded University of Utah Medical School. In 1909 he was elected president of the Salt Lake County Medical Association and served as vice president of the Utah State Medical Society for the second time.

The ensuing years were both productive and extremely strenuous. In addition to his local practice Behle made out-of-state consultations in Idaho and Wyoming, as well as to remote parts of Utah. After suffering two severe duodenal hemorrhages, Behle again traveled to the Mayo Clinic in 1916 where William Mayo performed a gastroenterostomy on him. The operation was not successful, and Behle suffered from ulcer disease for the rest of his life.

Following his recovery from his surgery, Behle joined the Voluntary Medical Service Corps for possible service in Europe during the World War I, but he was never called to active duty. From this point forward, Behle focused his interest in three areas: thyroid surgery, cleft lip repair, and brain surgery including “removal of tumors, draining of cysts, repairing compound fractures of the skull,” and treating hematomas. On at least two occasions patients were brought to Behle with broken necks and quadriplegia. On both occasions, he diagnosed cord compression and, upon emergency decompression, both patients fully recovered. Behle had spent a considerable amount of time working with Dr. Harvey Cushing, who is considered the father of modern neurosurgery in the United States. As Henry Plenk put it, “Based on his lifelong interest in surgery of the nervous system, his efforts in obtaining advanced training in neurosurgery and the amount of actual neurosurgery performed, Dr. Behle must be considered Utah’s first neurosurgeon.”

In 1920, Behle became a fellow of the American College of Surgeons. He had made formal application in 1914, but the impending war effort put the processing of applications on hold until 1920. In 1922, the Utah State Medical Association elected Behle to be its president.

From 1925 to 1929, Behle’s own health gradually diminished. In 1929, he made his final trip to Europe, again visiting the old world medical centers to observe surgical techniques and innovations. He spent much of his time at Saint George Hospital in London, which he had not previously visited.

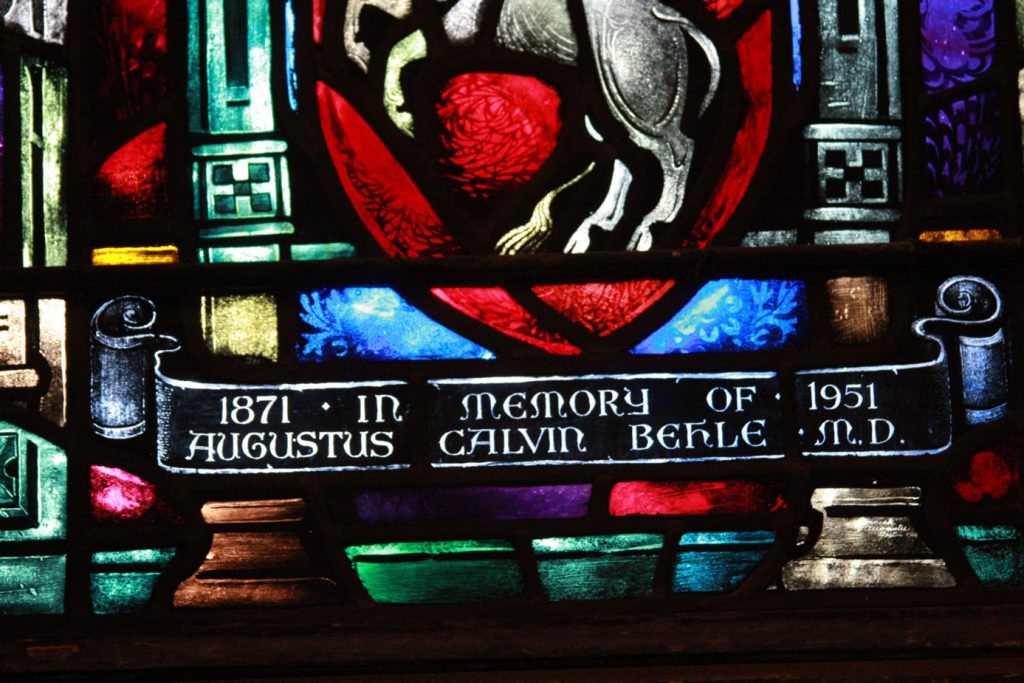

On returning to Salt Lake City, Behle attempted to rekindle his surgical practice but his career came to a sudden halt in August 1931. While preparing for a mastoid surgery on a boy who had arrived the night before from Idaho, Behle slipped on the tile floor of the operating room, broke his glasses, and severely lacerated his nose and forehead. From that point, Behle decided to retire. From 1931 until his death in 1951, Behle enjoyed a life of travel and leisure with his wife and three sons. He and his wife are buried in the Mount Olivet Cemetery in Salt Lake City.

Behle acquired an extensive library, and his ability to speak fluent German allowed him to keep abreast of the medical developments both in the United States and abroad. In addition to his trips previously cited, he visited the Mayo Clinic on several occasions. He studied with Dr. A. J. Costner in Chicago, Dr. George Crile in Cleveland, and John B. Deader at the University of Pennsylvania. When in Boston, Behle frequently visited Dr. Harvey Cushing at the Peter Bent Brigham Massachusetts General Hospital. Behle’s connections, talents, and travels opened many doors for him and put him a position to learn from some of the best professionals of his day. That, in turn, benefited Utahns. Dr. Behle was foremost an avid student and teacher of medicine and surgery, and he is considered the father of asepsis and neurosurgery in Utah and the West. Behle’s zeal to learn and teach were truly in the style of masters such as William Osler, who had taught him along the way.

Sources

Fifty-Second Annual Announcement and Catalogue of the Rush Medical College, Chicago, Ill. Chicago: Ellis, 1894. Available at archive.org, accessed July 6, 2020.

William H. Behle. Biography of Augustus C. Behle, M.D., with an Account of the Early History of St. Mark’s Hospital Salt Lake City, Utah. Ann Arbor, MI: Edwards Brothers, 1948.

Henry P. Plenk, ed. Medicine in the Beehive State, 1940–1990. Salt Lake City: Utah Medical Association, 1992.

Ralph T. Richards. Of Medicine, Hospitals, and Doctors. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1953.

Welch Medical Library, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland.