The Peoples of Utah, ed. by Helen Z. Papanikolas, © 1976

“The Oft-Crossed Border: Canadians in Utah,” pp. 279–301

by Maureen Ursenbach and Richard L. Jensen

Probably the first significant meeting of two Canadians in what is now Utah took place on the banks of the Weber River, east of present Ogden, on May 23, 1825. There, around mid-morning, Peter Skene Ogden, a Quebec-born Anglo-Canadian, leader of a Hudson’s Bay Company expedition, greeted a company of competitor trappers, “3 Canadians, a Russian, and an old Spaniard…under the Command of one Provost,” the French-Canadian Etienne Provost, born in Chambly, not twenty miles from Montreal where Ogden grew up.

There was no love lost between these two men; though the accounts indicate they parted in peace that same morning, there lay buried under their Canadian skins antipathies, the remnants of which burrow still into Canadian sensibilities–one was English-speaking, the other French. Not only that, the two men were competing for the same furs–reports suggest that Ogden’s orders were to make a fur desert of the area, so the American companies would lose interest in the region–and they were also jockeying for the loyalty of their men–at least one of Provost’s Canadians was a deserter from the Hudson’s Bay employ. Following the pattern of the English-French skirmishes in Canada the century before, the French-Canadian’s group had suffered an attack by Indians, riled to battle by the horse thievery of the British company’s men. That the two Canadians parted amicably is more to be wondered at than expected; the chauvinism of French-speaking and English-speaking Canadians in this century might not have been so easily restrained under such circumstances.

The backgrounds of the two men represent the two major thrusts of the Canadian national character. Provost, the French-Canadian trapper, born 1 785 of Albert and Marianne Provost, Quebecois of the farming community of Chambly, was typical of the coureurs de bois, the adventurous trappers who followed the rivers in search of wealth and excitement. Heading south, Provost joined the Chouteau-DeMun, an American fur company; he headed west and had been to New Mexico twice by 1823. An expedition took him over the Wasatch into the Great Basin by 1824, and a skirmish with the Snake Indians, possibly on the Jordan River, may have given him the first white man’s view of the Great Salt Lake.2

Peter Skene Ogden represents the other major Canadian population stream, the British-linked, English-speaking group. Although there have been in Utah some few immigrants with the French background, certainly the major portion of the Canadian population in Utah comes from a background like Ogden’s.

At the time of the Revolutionary War, and for a decade afterwards, there was a flow into Canada of “Loyalists,” British sympathizers who, uncomfortable with either the idea of revolution or the estrangement from their mother country, fled to British North America, the Canadas, Upper and Lower. Spreading out along the Saint Lawrence as far east as the Maritime provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia and as far west as the tip of Ontario’s Niagara Peninsula, they merged with the British-Canadian life, and found welcome. The United States-Canadian boundary continued to be, as it had been from the earliest colonial times, an oft-crossed border, as descendants of the Loyalists and descendants of their American cousins, antipathies forgotten, met and married and reared their families on either side, in either of two generally friendly countries.3

Ogden’s was one of those American-colonial families that found itself split in the 1776 trial of fealty. His Tory father Isaac, after an initial return to Britain, brought his family back to North America, to Quebec, Lower Canada. There, in 1794, his later famous son was born, and christened Peter Skene in honor of a Loyalist uncle. Immediately thereafter, the family moved up the Saint Lawrence to Montreal, a few miles from Chambly where Etienne Provost was a nine-year-old in his father’s house. But the two boys might as well have been on opposite sides of the continent, so divergent were their cultures. It was an economic, not a national force that brought them together for that brief meeting on the banks of Utah’s Weber River in 1825.

While the fur trade was sending “gentlemen adventurers” and “Nor’westers” into the Mexican territory that would someday he Utah, another force was gathering momentum in the East for a westward push. In upstate New York, the boy prophet Joseph Smith was gathering about him groups of believers who would follow him and his successors in stages to Ohio, Missouri, Illinois, and into the western wilderness, the Great Basin of the Rocky Mountains. That force would draw many Canadians in its magnetic field, pulling them along with its proselytes from New England, Great Britain, and eventually most of the countries of Europe.

Canada’s first introduction to Mormonism–the doctrines that shaped the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints–came in the summer of 1830, at Kingston, the Upper Canada city at the eastern edge of Lake Ontario. There, where the Saint Lawrence begins, was a stronghold of Loyalist stock, home of first prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, and breeding ground for the confederation that would come later. As well as being a politically active city, Kingston was religiously concerned. When Methodist preacher Phineas Young, brother to later prophet-leader Brigham Young, took the newly translated Book of Mormon to the Canadians at Kingston about one hundred fifty miles from his Mendon, New York, home, it was to a Methodist congregation that he preached the new gospel, to people who had already been forced to choose which camp of Methodism they would adhere to, the American or the English. Religious excitement was a part of their lives; it is no wonder the Mormons found a hearing in their midst.

Phineas Young, now a Mormon, returned to Kingston in 1832, and other missionaries followed, to other Canadian communities. Kirtland, Ohio, the second gathering place of the Mormons, was hardly a day’s wagon ride from Lake Erie and boat transportation across to Canada, and not much longer by wagon around the lake. From Kirtland traveled Joseph Smith himself into the Niagara Peninsula on the first of his two Canadian missionary journeys in 1833. From his and other missions converts were brought back, singly or in companies, to build the Zions of the new dispensation in Ohio and in the Independence, Missouri, area. Missionaries in Canada traveled chiefly among the English-speaking Canadians, for obvious reasons, proselytizing along the settled shores of the Great Lakes, through the Saint Lawrence Valley, into Quebec’s Eastern Townships, and on to Nova Scotia and New Brunswick in the first decade after the church’s founding. Among British immigrants–later church president John Taylor was one–they found their greatest successes.

There is as yet no published count of the numbers of converts the Mormons attracted in the two Canadas, but Richard Bennett, preparing a master’s thesis on the history of the church in Ontario, suggests that of the approximately fifteen hundred Ontario converts of the first two decades, probably a quarter emigrated, meeting the main body of the Saints at their stopping places along the devious trail to Utah. Add to that number the converts from other parts of Canada, and subtract from it the numbers who straggled along, some arriving in Utah, some never making the final push across the Great Plains. Then realize that of the people converted in Canada, not all were Canada-born; it is entirely reasonable that the 1850 Utah Census shows a total of 368 identified by their birthplace as Canadians.4 That number increased to 647 in the 1860 count, nearly leveling out to 686 by 1870, these being the years during which nearly all the Canadian immigrants to the Great Basin were Mormon proselytes gathering to their Zion in the West.

The Canada Centennial Project publication A History of the Mormon Church in Canada5 tells of the various Mormon missions to and emigrations from Canada in more detail than is possible here. Instead of merely making of that feast a hash, let us here have recourse to a few representative individuals, and permit their story to suggest that of so many like them.

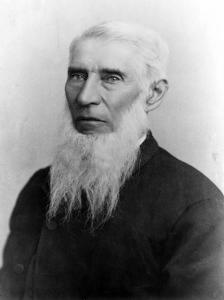

Prominent pioneer of 1847, this Canadian, William Empey, came to Utah with Brigham Young’s original company.

David Moore was born, the youngest of ten children, in Eardley, on the Ottawa River in what was then Lower Canada.6 His parents were American, the father having been born in New York, and the mother in the same county of Vermont that later would be the birthplace of Joseph Smith. Shortly after their marriage, the two moved to Canada, settling first on the Saint Lawrence, and then moving northward to the vicinity of Bytown, the present Ottawa. There the family was born, and there most of the ten children lived, bred prolifically, and died.

Of his family only David and his wife accepted the Mormon message to the point of baptism, along with a neighbor, Barnabas Merrifield, and his wife. In 1842, a year after their conversion, David succumbed to the familiar “spirit of gathering”: “Duty and my salvation called me to the headquarters of the Church,” he recorded later. The Moores and the Merrifields spent the summer preparing for their journey, and were about ready when David wrote, “I was informed by some of my friends that they heard several state their intentions of upsetting and mashing our wagons when we were passing Aylmer. I … concluded that they would have to catch me first.” A night was spent in preparations, and then:

About 3 o’clock in the morning of [August] 16th, I bid my father, mother, and the rest goodbye, and left the house, having a splendid horse for traveling, soon found myself near Aylmer Village. Barnabas and his wife [were’] close behind, he having a wagon and two horses. It was not yet light, and we passed by the place and did not so much as see a person in the street or about any of the houses. We passed on to Bytown [Ottawa] ferry and crossed over the river by the time the sun was an hour high in the morning.

The journey onward was relatively uneventful. Near Kingston the two families picked up a Brother Richard Sheldon, adding an extra load to their wagons. There, too, they were accosted by a Baptist minister who “readily saw by our mode of traveling that we were Mormons.” Moore does not identify what distinctive features marked their party, but the comment suggests that Mormon migrations in the Niagara Peninsula were not uncommon, a conclusion borne out by the naming of Archibald Gardner’s road from his settlement in Alvinston to the highway, the “Nauvoo Road.”

At Detroit the immigrants had to pass through customs. There was no office of immigration to demand any kind of visa; until 1907 no record was kept even of names, let alone nationality, of immigrants. But their goods were assessed and taxed. David Moore noted the arbitrariness of the assessment with some bitterness when, after he had paid his $12.60, leaving himself only fifty cents to his name, his friend Barnabas was let off with an easier, cheaper assessment of $8.00 because he was unable to pay his full toll. Such leniency towards immigrants bespeaks again the open invitation tendered to Canadians immigrating to the United States.

Once in the United States, the travelers suffered the frequent fate of brothers in the faith newly thrown together. Their falling-out left David and his wagon going on to Nauvoo alone and arriving there, after a six-week journey, with no home and no friend except his passenger Richard Sheldon. Even he would have deserted his benefactor had not Moore pressed his case earnestly. So Sheldon took him to the one-room cabin of his friends, a Canadian family, where the Moores found begrudging hospitality. Their sojourn in Nauvoo followed the inauspicious precedent set by the first week, during which the hay Moore hauled for his host and himself was stolen for a widow next door, he came down with the “chills and fever” which would plague him all that winter, and he heard the Prophet Joseph Smith predict that though the Saints “should never be driven from their habitations in Nauvoo…he would not promise that they would not be coaxed to leave.”

Moore’s account of his Nauvoo experience details the marshaling of opposition to the Mormon presence, the murder of Joseph and Hyrum Smith, the takeover by Brigham Young and the Twelve, the repealing of the Nauvoo Charter, and his own activities as a member of Nauvoo’s whittling and whistling militia. (Their arms confiscated, Nauvoo defenders would escort the unwelcome from their city by moving ominously near, whittling away with their large knives as they came.) All in all, Nauvoo was a dark period in the lives of David and Susan Moore.

By May 1846 Moore and his family were on their way west. During a three-year layover in Bentonsport, Iowa, David, obviously considering himself as qualified to vote as his American-born neighbors, involved himself in the local politics. His vote, however, was challenged, not because he was Canadian, but because he was Mormon. Finally, in April 1849, he loaded his wagon once more for the last leg of the hegira, and on October 20, 1849, he entered the valley.

Moore was more happily absorbed into the Deseret society than he had been in Nauvoo. Settling early in Ogden, he became the first recorder there, then county clerk and city and county treasurer. He served on the city council, on the stake high council, and in the Utah militia. As befitting to his ecclesiastical role, he took two more wives shortly after his entrance into the valley and by them raised a posterity long since interwoven into the fabric of Utah’s people. It is probable that the Canadian segment of their background is long since forgotten.

David Moore’s earliest Mormon antecedents in the Great Basin kingdom were the six (at least) Canadians of Brigham Young’s pioneer company who entered the valley in July 1847.7 Three of them might well have known each other as converts in Canada; Barnabas Adams, William Empey, and Charles David Barnum all lived near Brockville, on the Saint Lawrence River, when they heard and accepted the Mormon doctrine and moved their families to Nauvoo. Two other Canadians in the pioneer company came from remoter regions: John Pack from New Brunswick and Howard Egan from Montreal. Roswell Stevens was fruit of Joseph Smith’s 1833 mission into the Niagara Peninsula. It is more the rule than the exception that Canadians do not clan together; except for Barnum, who eventually settled not far from his compatriot Adams, the, group seems to have formed no lasting bonds based on shared nationality.

A pioneer of September 1847, Joshua Terry is part of a remarkable family saga that, in its wider implications, suggests the elements of the Canadian experience in pioneer Utah.8 His grandfather, Pennsylvania-born Parshall Terry II, deserted the Revolutionary Army and fled to Canada. However, Joshua’s father, Par-shall III, was later born in New York. Parshall III had seven children born in Palmyra and the last six, including Joshua, at Albion, Upper Canada. The parents and most of the children converted to Mormonism in 1838, emigrated to Missouri, and followed the body of the Mormons to Illinois and then to Utah. Joshua became a mountain man and associate of Jim Bridger, and his first two wives were Indians. When most of his family came west in 1849, he and Bridger helped them along their way at Fort Bridger with six fresh oxen to pull the wagons on the last leg of the trek.

Joshua’s sister Amy married one of Brigham Young’s early Canadian converts, Zemira Draper, who, with his brother William, founded Draper, Utah. Many of the Terry family moved there, some for the rest of their lives. But Zemira and William Draper and James and Jacob Terry were called to the Cotton Mission and settled in faraway Rockville. There Zemira helped build a sawmill, a molasses mill, and a cotton mill, all of which used water power from the Virgin River.

Joshua eventually settled down at Draper and often served as a link between the whites and the Indians of the Great Basin. His half-breed son George, appointed by church leaders to work with the Shoshones, eventually became one of their chiefs. Thus the family blended into the Utah environment and even into the native populace of the area.

A long look through the 1850 United States Census for Utah picks up the names of many Canadians whose stories form a significant part of the Utah picture. Some of them, like Stephen Chip-man, had children who later figured prominently, one of them, James, as Utah National Bank president. An indication of mobility and adventuresome spirit, twenty-one year old Washburn Chip-man, James’s brother, was picked up twice in the census: once at his parents’ home in Great Salt Lake County, and later, at age twenty-two, in Iron County. Robert and Neal Gardner, sons of Scottish-born Archibald Gardner who built gristmills first in Ontario and then in Utah, appear as the only members of their family to show Canadian origins, having been born in Alvinston, the Ontario town their father founded. Only one Canadian family is listed in the Manti region; and the extended family of Dudley and Lemuel Leavitt, from Lower Canada, represents the larger part of the Canadian population of Tooele County.9 (A third Leavitt, Thomas, became one of the counter-movement, emigrating from Utah to Canada in 1887.) Most of the immigrants shown on this census originated in either Upper or Lower Canada, though some indicate Nova Scotia or New Brunswick origins. Not surprisingly, the only French-sounding name, Lamoreaux, belongs to people with Anglo-sounding Christian names, suggesting that the Mormon message had not yet reached the Canadiens.

Most of the Canadian-born converts to Mormonism who moved to Utah arrived before 1860. Few Canadians came during the next decade. Indeed, very little effective Mormon missionary work was done in Canada during the last half of the century, and only a few straggling faithful remained in Canada or the Midwest to make the trip to Utah after the “Utah War” of 1857-58.

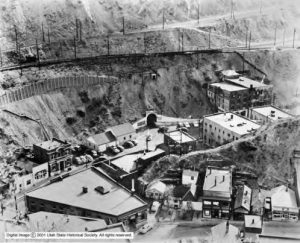

Lower Bingham Canyon was known was Frog Town because of the French-Canadians who lived there.

Canadians in Utah had slid inconspicuously into the pattern of life and commerce in developing Utah Territory in the 1 860s when Halifax-born George B. Ogilvie, lumbering in Bingham Canyon in 1863, made a discovery that reshaped the economic life of Utah, and with it the Canadian population of the territory: there was silver-bearing ore in the rocks of the canyon. Utah’s mining boom had begun.10

The mines and the arrival of the railroad in 1869 initiated the wave of non-Mormon Canadians that reached Utah in the 1 870s. By the 1880 Census, they, along with the earlier Mormon Canadians, had fit into nearly every aspect of life in the territory. Most were listed as being associated with farming and mining, either directly or in supporting enterprises. Besides those there were merchants–dry goods, liquor, tobacco, lumber; doctors; a music teacher; a probate judge; a dressmaker; weavers and spinners; a printer and a saloon keeper. There even was a Canadian prostitute, a Miss Vinnie Snow, as she called herself, doing business on East Temple Street in Salt Lake City. The interesting quirk in the 1880 Census report on Canadians in Utah is the cluster of them in Summit and Beaver counties; a closer look finds them, many of them from mining communities of Canada’s Maritimes, working at the Frisco and Park City mines. And of the Canadians in mining, none are more interesting, if atypical, than the bosses of the Silver King mines.

David Keith was a foreman at the Ontario mine when young Thomas Kearns reported to him in the spring of 1883.11 The stories of their lives to that time are as intriguing as is the history of their mutual accomplishments after their meeting. Keith had come by circuitous route from Mabou on Nova Scotia’s Cape Breton, where he was born in May 1847, the youngest of thirteen children of a Scottish immigrant miner who died when David was fourteen. In the gold mines of Nova Scotia the young man won his grubstake, and in 1867 left for California. Within two years he had found a place in Virginia City, Nevada, where he continued until 1883, the year he was summoned to Park City to install at the Ontario mine the great Cornish pumps used to clear the shafts of water during construction. There he met Thomas Kearns, fifteen years his junior, a fellow Canadian. It is doubtful that their being compatriots was much more than an interesting coincidence to the Scotsman’s son Keith and Kearns, Canadian-born Irish Catholic whose family had left Woodstock, Ontario, where Thomas was born, for a colony of Irish in Nebraska. Probably more significant than shared national origin is the sharing of an adventuresome spirit which is necessarily part of the mentality of any hardy soul who will try life in the less hospitable regions of North America. Kearns felt the wanderlust even younger than Keith. By the age of twenty-one he was on his way to Butte, Montana, having already worked as a freighter and a miner in the Black Hills, as a cowboy in the Dakotas, and as a miner and a teamster in Tombstone, Arizona. At Pocatello, Idaho, on his way to Butte and “the richest hill on earth,” someone told him of Park City. He entered the boomtown of three thousand population in June 1883 and there met his future partner, who had arrived just two months earlier.

The story of the Mayflower mine and its subsequent expansion into the Silver King Coalition Mines is a long and exciting one, dealt with in sources readily available.12 That not only Kearns and Keith but also Windsor V. Rice13 and James Ivers14 of the initial group were Canadians is a detail that slips past the researchers. Ivers and Rice both left their Quebec homes, young and alone, just as Keith and Kearns did, and who knows how many other young Canadian adventurers whom fate, or luck, for good or ill, led to Utah. These four left footprints that remain these years later:

Keith O’Brien store, the Kearns Building, records in the United States Senate and the Utah state legislature (Kearns and Ivers, respectively), two mansions still standing on Salt Lake City’s South Temple Street, the Salt Lake Tribune, and independent fortunes now diffused among descendants of the four magnates.

During those beginning days of the mining and railroading booms in Utah, when non-Mormon itinerants were finding their ways into the territory, there finally appeared aQuebecois, identifiably and distinctly French-Canadian. Amable Alphonse Brossard, “Frenchy” to his Utah comrades, was born the seventh generation in Canada in 1846 at Laprairie, near Montreal.15 He may have left Laprairie for the same reasons that Etienne Provost left Chambly: for adventure, for fame, for the chance to make his fortune. But the times were different; rather than trap the streams for fur as Provost had done, Brossard worked the hills for gold. He worked in the mines in the Fort Benton, Montana, area, and then ran a dairy there for a time. Finally, a freighting line brought him to Utah, to a rooming house in Richmond, Cache County. There he met and married pretty Mary Hobson, and two deep heredities coalesced:

Mary was as many generations American as Alphonse was Canadian. They reared their children in Cache Valley; in 1971 the count of their descendants had reached 168, among them, Edgar B. Brossard, chairman of the United States Tariff Commission for many years and twice president of the French LDS mission. The French culture seems not to have passed in the rest of the family beyond Alphonse, though, and only the purposeful search for family connects the Utah Brossards to their French Canadian past.

Canadians continued their influx into Utah in moderate numbers until about the time of World War I, with a marked in-crease immediately after the turn of the century. Some of them were apparently associated with the mines in Juab and Tooele counties during periods of high activity there. Increasingly they concentrated in the metropolitan areas, in Salt Lake County, where there were nearly a thousand Canadian-born in 1910, and in Weber County.

Meanwhile, a meeting between Charles O. Card and Mormon church president John Taylor, both in hiding from federal marshals seeking to arrest them on the “unlawful cohabitation” charge under which polygamists were prosecuted, led to the migration which, reversing itself, would in the long run provide Utah with most of its Canadian immigrants.16 Card, pioneer settler and stake president in Cache County, had concluded to take part of his extended family–he had three wives at the time–and move to Mexico, but the president’s approval was necessary. Card family history recounts the response of Taylor, an English immigrant who had lived in Toronto for several years: “No,…go to the British Northwest Territories. I have always found justice under the British flag.” Whether the quotation is accurate or not, it became a part of the attitude that the settlers who followed Card into Canada built into their children, and the expectation was not without grounds.

The story of Card’s 1886 exploration of southern British Columbia and Alberta, and his subsequent choice of the Lee’s Creek site (later Cardston, Alberta) is an oft-told tale in the histories of the Mormons in Canada, as is the account of the arrival of the first settlers the following spring. Of the forty-one Utah men who, with their families, had originally agreed to follow Card to refuge in Canada, eleven made the trip, moving in small companies of one or two families each. The journey paralleled in many ways the Winter Quarters-Great Basin trek of forty years earlier, including the poignancy of the arrival reflected in the tearful comment of four-year-old Wilford Woolf on being told this grassy prairie would be home:

“Ma,” he quivered, “where’s all the houses?”17

Settlement moved rapidly. Sterling Williams wrote back to his Utah grandmother after a week in Canada that already the settlers had four acres of the dark, rich earth planted in wheat, oats, and potatoes, and that a bed of coal had been found three miles away.18 The unseasonal snow which had fallen the first night of their arrival presaged a long cold winter, so houses were speedily erected, and a town sprang up. They named it Cardston.

Whether they actually felt it or not, the Mormons made it apparent to the old settlers that they meant to stay in their new colony, and their immediate neighbors in Lethbridge and Macleod received them warmly. Some Gentile opposition to the Mormon incursion was registered in newspapers as far away as Montreal, but local observers foresaw only good to come of the settlement. The Canadian government, using the recently completed railroad as a drawing card, had been encouraging settlement of the “Palliser triangle,” the southern portions of Alberta and Saskatchewan. A Mormon delegation to Ottawa, though they did not return with the concessions they asked–no, Mormons may not practice polygamy in Canada–did obtain the same welcome tendered to all immigrants.

From their arrival in Canada there had been an ambiguity in the Mormons’ own attitudes towards their new homeland, an ambiguity still present in the grandchildren of the early settlers. William Woolf, born in Cardston in 1890, remembered that “We never spoke of Utah’; it was always down home.'” When the July 1 Dominion Day celebration took place that first year in the new colony, it was designed as much to win the approval and confidence of the old settlers as to instill in the new ones a loyalty towards Canada. What happened to that observance in later years, however, suggests the paradox of the community’s attitude: from July 1 to July 4 became one long celebration, including a program of speeches praising, on the First, Canada’s fair government and good land; on the Third, Cardston’s founding; and on the Fourth, the American heritage of freedom and liberty dating back to the Revolution. The interim was filled with baseball, tug-o-war, dances, band concerts, horseshoes, foot races, horse-pulling contests, and horse races in which the Indian contestants from the nearby Blood reserve invariably showed well.19 And later the same month, on July 24, the en-trance of Brigham Young into the Salt Lake Valley would be celebrated with equal enthusiasm. That all these loyalties could be maintained in the consciousness of a single community attests to the basic similarity of the mores and customs of Canadians, Americans, and Mormons. Many Canadian-born Utahns to this day claim they hold “dual citizenship,” a legal status now nonexistent. Valid or not, the claim itself is significant: it represents the wish to hold to both loyalties at once.

Card and his associates probably intended their stay in Canada to be temporary: once federal prosecution for polygamy ceased, they expected to return. The October 1890 LDS conference in Salt Lake City, however, brought with it a series of surprises to Card, and reshaped the lives of Utahns of his generation and at least three to follow.

Expecting to face a trial and fine for his own “illegal cohabitation,” Card instead found himself listening in conference to Wilford Woodruff, then president of the church, rescinding the practice of polygamy in his famous Manifesto. A mixture of responses greeted the announcement: “To day the harts of all ware tried, but looked to God and Submitted,” wrote Card’s mother-in-law Zina Young, widow of Brigham Young.20 She and Card, most certainly, expected the recall from Canada for him and for her daughter, his wife. But there were other plans, and Card found himself released from his ecclesiastical responsibilities in Cache Valley and assigned indefinitely to Canada. The new colony, already more than mere temporary refuge for beleaguered polygamists, was to become a permanent settlement to support and be supported by the Utah church, a nucleus for an expanded Mormon colonization complex. Card and his brethren in the faith acquiesced, took out Canadian naturalization papers, and encouraged all new settlers to do likewise, and to claim lands under the Canadian Homestead Act.

Mormon settlements in Alberta radiated out from Cardston. By 1894 some 674 settlers, most of them from Cache, Weber, and Box Elder counties, were expanding the four main settlements. By the turn of the century the church was calling irrigation missionaries, and towns as far away as Taber, east of Lethbridge, were growing. Mormon apostle John W. Taylor, then living in Cardston, persuaded Utah financier Jesse Knight to invest in cattle lands in the area. At Raymond, Knight built a factory for refining beet sugar, and soon the church established a high school there, calling teachers from Utah and Idaho to staff it.21

Not all the settlers, of course, were officially sent. Homer M. Brown, for example, was feeling the crunch of land availability for his large family in the Salt Lake Valley and so moved his wife Lydia and their twelve children north to Spring Coulee in 1898, where their last child was born in 1901. They settled finally in Cardston, where their second son, Hugh B., later to become prominent in Utah legal and government affairs, and counselor in the LDS church First Presidency, met Zina Card, daughter of Cardston’s founder, whom he later married. They eventually brought their family back to Utah. Brown, reflecting on his mixed Canadian-American background, found it difficult to declare a first loyalty; he had been an officer in the Canadian armed forces, had been a Utah state commissioner and candidate for the United States Senate, and had practiced law in both countries. While he had willingly become a Canadian citizen with his family, he had as willingly become a naturalized, repatriated American.22

Not all Canadian-American settlers of the Alberta colonies felt Brown’s ambivalence; his mother Lydia, for example, was deeply hurt at leaving Utah, as were many of the women. Mildred Cluff Harvey, for one, moving with her husband Richard C. from Heber Valley, where there was no room, to Mammoth, Alberta, where there was nothing but space, remained, her daughter later recounted, “a Utahn to her death.” Richard, on the other hand, was “a Canadian from the time he first set foot on Canadian soil,” where, in his own words, “when I saw the abundance of feed and grass everywhere and nothing to feed but my cattle, I thought this was paradise indeed !” Their daughter, Mildred Jennie, aged nearly four at their arrival in Canada, cried to return “home to Utah.” And did, years later, to become superintendent of nurses at the Budge Hospital in Logan.23

This Mildred Harvey was part of a tide that has swept Canadian descendants of Utahns back to their parental homeland since the first generation of pioneer children matured: the pursuit of higher education. Even if the University of Alberta had been founded earlier than its 1906 beginning, it is likely that the Mormons would have still returned to Utah. Many had relatives in Cache Valley, where Brigham Young College was offering religious as well as practical and academic courses. As early as 1894 John A. Woolf from Cardston was attending there, and by 1900 three others had followed. Enrollment of southern Alberta Mormons rose steadily to eleven in 1903, dropped, then peaked again with twenty students in various departments in 1907. In the meantime the reputation of Utah State Agricultural College (now Utah State University) was spreading, and in 1902 Seymour Smith registered as the first Canadian student there. The same year, four students from the Alberta colonies enrolled at Brigham Young University in Provo. The stream of Canadian Mormons to that school has continued unabated to the present, most likely because parents see their offspring there as resting safe in the lap of the church. The last available report from that school, recording 1973 attendance, shows 505 Canadian students there.

Strangely, the University of Utah attracted only a dribble of the Canadian student migration; its records show no more than two Canadian students in any term up to 1916, whereas BYU had reached twelve in 1914 and USU fourteen in 1916. The University of Utah showed in 1973 only thirty Canadian students. There were and are other factors than Mormon-linked ones affecting enrollment, of course, but no analysis of foreign student population in Utah is available delineating causative forces.

The student population has been dealt with in this context for one basic reason: a very loose survey of Canadians currently living in Utah, and those of the generation just deceased, shows that a preponderance came south first as students, then stayed to practice their trades and professions here. Until 1968, when immigrating workers were first required to meet stringent labor certification requirements, procuring a visa was almost pro forma for Canadians; so all that was required of a graduating student wishing to remain, or any Canadian, for that matter, wishing to take up residence in Utah, was a few forms to fill out and a few months’ patience. Prior to 1924 not even a visa was required, and after that the help of a “sponsor,” a well-established resident willing to vouch for the candidate, smoothed the way. In 1965, however, Canadians, like all other nationals, were put on a “preference quota system,” and the shape of Canadian immigration changed sharply as a result.24

From World War I until the 1930s the number of Canadians in Utah decreased almost as rapidly as it had increased before. But in 1940 a resurgence of Canadian immigration began, and the Canadians in Utah more than tripled their numbers between 1930 and 1970. Immigration figures for the past two decades reveal that fluctuations in Canadian immigration to Utah have paralleled those to the United States as a whole to a striking degree, indicating that national immigration policies and economic conditions have become more important determinants of this immigration than any particular conditions in Utah. Canadian immigration to Utah rose to a peak of 311 persons during the year 1965, and although it dropped dramatically after the application of the quota system, Canada has supplied more immigrants to Utah than any other country each year since 1962. At last count there were slightly more than four thousand Canadians in the state, including about seven hundred students, and about another seven thousand persons having one or more Canadian-born parents.25 That relatively few of the immigrating Canadians have become United States citizens in the recent years is perhaps the best indicator of the ambivalent attitudes of the immigrants: they feel themselves strangers in neither location and so sense little pressure to abjure either country’s citizenship.

In a recent interview Gerald O. Fasbender of the United States Immigration and Naturalization Service office in Salt Lake City, affirmed that nearly all–he estimated 95 percent–of the recent Canadian immigrants landing in Utah initiated their applications through the United States consulate in Calgary, the nearest office to the Southern Alberta concentration of Mormons. In the absence of complete figures, but on the basis of his experience in the Utah office, Fasbender suggested that the majority of Canadians emigrating to Utah choose this location “because of the [LDS] church.”

What of the Canadians in Utah now? In a western setting, the Anglo-Canadians are easily lost in the crowd, unidentified except by a very astute listener who detects a slightly different dialect. “Canajan,” as a recent book transliterates it, is recognized by the shortening of the vowels, especially the ou diphthong, and a frequent inclusion of the shibboleth “eh?” into the middle or, more frequently, at the end, of sentences.26 Even this difference all but disappears in the accent of the southern Alberta Mormons whose own “Mormon drawl” distinguishes them in Canada but assimilates them in Utah. French Canadians, of course, are easier to identify. Although a phenomenally large number of present-day Canadiens are bilingual, there is nearly always a trace of the mother tongue in their English. The attitudes Canadians express are even more revealing: French Canadians may let slip a trace of the resentment they feel towards the Anglo-Canadian domination of their economy. By the same token, Anglo-Canadians may show resentment of the American big brother, an attitude, says Wallace Stegner, similar to that of the American westerner towards eastern influences on his culture.27

No melting pot, Canada has rather preferred to weave its people, native, British, French, eastern European, and others, into a variegated fabric that encouraged their distinctness. Multi-culturalism is now explicitly the official policy governing social legislation in Canada. The loyalties of Canadians in Utah, then, are more likely directed towards a region than towards the country itself. The Canadian Club in Salt Lake City is an example. At least as early as the 1950s, Canadians would gather in Liberty Park on the First of July, Dominion Day, and make their own national observance. There would be a Canadian flag on the piano, and “0 Canada” to begin the ceremonies. A speech, a few musical numbers, and then “God Save the King” (or Queen) to round out the program. There would follow games for the children, a potluck supper, and the inevitable visiting of friends from former years. One year recently, however, the organizers of the picnic advertised the event in local newspapers. The usual crowd of southern Alberta Canadians, most of them Mormon, was augmented by several eastern Canadians who brought the more typically Canadian accoutrements of a celebration: their beer and other bottles. The mixture of religious and regional backgrounds was a stronger divisive force than Canadian nationalism was a unifying one; the celebration the following year returned to the limited observance of the few “old-timers.” The celebration in 1974 involved some three families.

Canadians in Utah now, as in the past, have found ingress into the whole commercial and professional life of the state. Some have distinguished themselves in their fields; many have made notable contributions. Any list of such people would be at best spotty, but let there be here a few representative names.

It is reasonable to expect numbers of Canadians to be involved in education in Utah, since so many of them came here originally for higher training in teaching and school administration. DeVoe Woolf and Marion C. Merkeley came from the Mormon colonies to become, respectively, high school principal and state superintendent of schools in Utah. Stewart Grow, Heber Wolsey, and Curtis Wynder are BYU administrators, and Harold W. Lee and Oliver Smith are faculty members there. Increasingly, however, educational institutions are attracting as faculty other than their own graduates, and Canadians are coming to Utah via institutions elsewhere. Maxwell M. Wintrobe, hematologist of the University of Utah’s College of Medicine, came from Manitoba via Tulane University in 1943 to help establish the four-year medical school here. Ukrainian Canadian Orest G. Symko finished his student work in physics at Oxford before joining the faculty at Utah. At USU, Canadian William H. Bennett was dean of the College of Agriculture; James Bennett and William Lye are heads of departments; and Bruce Anderson is director of international programs.

In medicine, Morgan Coombs, Harris Walker, Ulrich Bryner, and LeRoy Kimball are representative of Canadians who practice or practiced in Utah. Kimball Fisher and Wallace Johnson represent pharmacists. Canadian lawyers Wilson McCarthy and Emmett L. Brown served here both as attorneys and as judges. McCarthy is more remembered for his contributions in the Reconstruction Finance Corporation and for having taken over receivership of the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad and reviving the company.28

In music are Canadian brothers Ralph and Harold Laycock; in sports, Alan R. (Pete) Witbeck; among authors, W. Cleon Skousen. LDS religious leaders N. Eldon Tauner, of the church’s First Presidency, the late Hugh B. Brown of its Quorum of the Twelve, William H. Bennett, an assistant to the Twelve, and Presiding Bishop Victor L. Brown are all Canadians, adopted or originally.

It is impossible in practical terms to delineate the impact of Canadians on the social, cultural, political, and economic life of Utah. Canadian stock has long since woven itself into the whole fabric of the state, and newly arrived Canadians blend almost without a trace into the changing pattern. But if the individual fibers can no longer be distinguished, still the fabric itself has been strengthened by the added strands.

1David E. Miller, ed., “William Kittson’s Journal Covering Peter Skene Ogden’s 1824-1825 Snake Country Expedition,” Utah Historical Quarterly 22 (1954): 137. Cf. David E. Miller, ed., “Peter Skene Ogden’s Journal of His Expedition, 1825,” Utah Historical Quarterly 20 (1952): 181. The basic material on Ogden is from Ted J. Warner, “Peter Skene Ogden,” Mountain Men and the Fur Trade, ed. LeRoy R. Hafen, 10 vols. (Glendale, Calif., 1965-72), 3:213-38, and that on Provost, from Hafen’s own chapter, “Etienne Provost,” 6:387-98 of the same work.

2 Hafen, “Provost,” pp. 373-74.

3 Fred Landon, Western Ontario and the American Frontier (Toronto, 1941), p. 61 quotes a droll comment on Canadian-American intermarriage shortly following the war of 1812. One Adam Fergusson, a visitor in Canada, received this reply to his query as to the likelihood of another United States? Canadian war: “Well, sir, I guess if we don’t fight for a year or two, we won’t fight at all, for we are marrying so fast, sir, that a man won’t be sure but he may shoot his father or his brother-in-law.” The original source is given as Adam Fergusson, Practical Notes Made During a Tour in Canada and a Portion of the United States in MDCCCXXXI [1831], 2d ed. (Edinburgh, 1834), pp. 147-48.

4 While the official compendium of the census for 1850 lists only 338 born in British America, at least 368 can be counted in the manuscript census.

5 A History of the Mormon Church in Canada (Lethbridge, Alberta 1968). A pioneer work in the area, the book draws heavily (though deleting some of the most significant material) on the dissertation of Melvin S. Tagg. It is hoped that detailed studies of Mormons in Canada will follow this general overview.

6 David Moore, Autobiography and Journal, in “Compiled Writings of David Moore,” typescript, Archives Division, Historical Department, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City. All the David Moore material in this account is drawn from this source, supplemented with the account in the “Journal History,” a daily compendium assembled in the LDS Archives, s.v. “David Moore.”

7 Andrew Jenson, LDS Biographical Encyclopedia, 4 vols. (1901-36; reprinted., Salt Lake City, 1971), 4:693-725, lists with biographical notes the members of Brigham Young’s first company, including the six mentioned here.

8 Nora Hall Lund, comp., Parshall Terry Family History (reprint ed., Salt Lake City, 1963).

9 A more complete account of the family is contained in Juanita Brooks, On the Ragged Edge: The Life and Times of Dudley Leavitt (Salt Lake City, 1973).

10 S. George Ellsworth, Utah’s Heritage (Salt Lake City, 1972), p. 262.

11 “Thomas Kearns,” and “David Keith,” Utah Since Statehood, Noble Warrum, ed., 4 vols. (Chicago and Salt Lake City, 1919-20), 2:5-9, 26-30; Kent Seldon Larsen, “The Life of Thomas Kearns” (Master’s thesis, University of Utah, 1964).

12 Oscar F. Jesperson, Jr., “An Early History of the Community of Park City, Utah” (Master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1969); Dean Franklin

Wright, “A History of Park City, 1869-1898” (MS. thesis, University of Utah, 1971).

13 “Windsor V. Rice,” Sketches of the Inter-Mountain States (Salt Lake City, 1909), P. 169.

14 Hon. James Ivers,” Warrum, Utah Since Statehood, 2:570-71; “Hon. James Ivers,” Biographical Record of Salt Lake City and Vicinity (Chicago, 1902), pp. 132-33.

15 Edgar Brossard, Alphonse and Mary Hobson Brossard (Salt Lake City, 1972).

16 A. James Hudson, “Charles Ora Card, Pioneer and Colonizer” (M.A. thesis, Brigham Young University, 1961).

17 Ibid., p. 112.

18 Sterling Williams to Zina D. Young, June 13, 1886, Zina D. Young Collection, in private possession. The letter is mistakenly dated; it should read 1887.

19 Interview with William L. Woolf, July 23, 1974.

20 Zina D. Young, Diary, October 6, 1890, holograph, in private possession.

21 J. Orvin Hicken, comp. and ed., Raymond, 1901-1967 (Lethbridge, Alberta, 1967), pp. 19, 30-31.

22 Interview with Hugh B. Brown, August 19, 1974.

23 “A Brief History of Richard Coope Harvey (1865-1950),” Four Leaves From History, comp. and ed. Lucile H. Ursenbach, (Calgary, Alberta, 1973), p. 16; interview with Lucile H. Ursenbach, August 20, 1974.

24 Interview with Gerald 0. Fasbender, officer in charge, Salt Lake City office of U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, July 25, 1974.

25 1970 Census, vol. 1, part 46, pp. 113, 134, 279, 282. There is a discrepancy of 1,443 persons between the figures given on p. 282 and all the other totals given for Canadian-horn persons. Certainly this cannot be entirely explained by differences in sampling. The authors have assumed that the higher figure given on p. 282 must be more accurate in view of the relatively heavy influx of Canadians during the 1960s. If the lower figure were correct this would indicate that there has been an amazingly high turnover of Canadian immigrants in Utah through death and emigration.

26 Mark M. Orkin, Canajan, Eh? (Don Mills, Ontario, 1973). The book is a clever poke at Canadian speech and Canadian ways. Its description of the use of “eh?,” pp. 35-38, is delightful as well as observant.

27 Wallace Stegner, “Letter from Canada,” American West 11 (January 1974) 28-30.

28 Robert A. Athearn, Rebel of the Rockies (New Haven and London, 1962), pp. 307-12.