Kenneth W. Baldridge

Utah History Encyclopedia, 1994

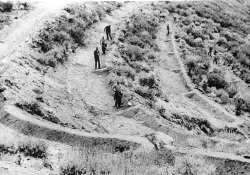

Civilian Conservation Corps at work in Davis County, Utah

When Franklin D. Roosevelt took over as president in March 1933 the country was in the midst of the worst depression ever experienced in the United States. Among the organizations established to help relieve the situation was the Civilian Conservation Corps, not only one of the first to begin operations across the country but also one of the most successful of the various “alphabetical agencies” of the New Deal period. Originally referred to only as Emergency Conservation Work (ECW), Roosevelt’s CCC designation had been in popular use from the beginning, and its nicknames “Three C’s,” “Triple C’s,” or simply “The C’s” were widely used. The CCC was designed to simultaneously solve two of the major problems facing the country: provide financial relief and help implement conservation projects.

Several government departments were included among the “technical agencies” which supervised the work of the 116 camps that existed at one time or another in twenty-seven of Utah’s twenty-nine counties over the nine-year life of the CCC. The United States Forest Service supervised forty-seven camps; the Division of Grazing—now Bureau of Land Management—had twenty-four camps working on erosion control projects and building reservoirs. The six Bureau of Reclamation camps worked primarily on irrigation schemes, especially the construction of the Midview Dam and lateral canals on the Moon River Project in the Uinta Basin, one of the biggest projects in the state. Range reseeding was one of the main activities of the eight camps of the Soil Conservation Service. The National Park Service had seven camps, primarily in Zion and Bryce National Parks, and it also, along with the city of Provo, jointly supervised the only “Metropolitan Area” camp in Utah. In addition to these, there were also camps assigned to the state of Utah for erosion control and work on state parks, as well as for the U. S. Biological Survey, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and the U. S. Army. Work assignments for the camps were laid out and supervised by the technical agency in charge, although each camp was under the command of a regular or reserve office of the U. S. Army, which handled the logistics of supply and administration for the program.

The first CCC camp to be completed in Utah was located about ten miles up American Fork Canyon. After establishing a temporary camp, forty young men, or “enrollees,” most of whom were between the ages of eighteen and twenty-three, began construction of two barracks on 17 May 1933. It was July, however, before seventy-five LEMs, or “local experienced men,” arrived from Salt Lake County to fill the complement of two hundred men. The LEMs were hired from the ranks of unemployed carpenters, farmers, lumbermen, miners, and others who had experience in handling horses, men, and equipment, and who could serve as project leaders. While the population of the state determined the number of junior enrollees, the quote of LEMs was based on the number of camps in the state.

The state was treated quite well by the CCC due to the great availability of projects, and for most of the life of the Civilian Conservation Corps, Utah had between thirty and thirty-five camps at any given time. Based on its population, Utah generally had a higher percentage of its manpower quota employed than did most of its neighbors. There were 16,872 junior enrollees from Utah, 746 Indian enrollees, and 4,456 supervisory personnel. In all, there were 22,074 Utah men who were provided employment by the CCC during the nine-year period, plus an additional 23,833 individuals from out of state who worked on projects in Utah.

There were enrollees from the streets of New York City and Ohio, as well as mountain boys from Virginia, Indiana, Kentucky, North Carolina, and West Virginia. Regardless of where the enrollees were from, the camps were occupied by young men who had been through some extremely difficult times and recognized the emergency program as an opportunity for basic survival and even for advancement. The work of the CCC was varied. The corpsmen built trails, phone lines, campground improvements, fences, bridges, cabins, and low-standard roads; they built check and silt dams for flood control and the curbing of erosion; they dug out poisonous larkspur and other noxious weeds and instituted insect and rodent control. Several of the Forest Service’s CCC camps began many of the loop roads through the canyons of the Wasatch Range. In addition to these jobs at which they regularly worked, the CCC force constituted a 5,500-man fire brigade, units of which could be mobilized any time for forest fire suppression.

In September 1933 the Herald Journal of Logan reflected the attitude prevailing at the time. “One of the most completely successful of all the items on the New Deal program seems to be the forestry work of the Civilian Conservation Corps. . . So well is the project working out that a person is inclined to wonder if it might not be a good thing to make this forest army a permanent affair. . . All of this of course would be pretty expensive but it might be money well spent. . . certainly the question deserves serious consideration. This forest army is too good an outfit to be discarded off-hand.”

There were plenty of projects to support this well-deserved praise: the riprapping along the Virgin River, the bridge over the San Rafael River, the campgrounds up Logan Canyon, the rodeo grounds at Tooele, the Bear River Refuge, the terracing overlooking Willard and Bountiful, and the dozens of reservoirs and springs on the western desert would all qualify. There were also some major projects to which individual camps were devoted for several years. The construction of all-weather roads into Boulder, for example, occupied CCC crews from 1933 until 1941 before that isolated community could be linked year-round to the outside world. Other major projects included five years spent improving bird refuges on Bear River and Ogden Bay.

The CCC performed admirably in many emergency situations over the years. The young men all attended fire-fighting school their first week in camp and the training was put to use many times. The early 1930s was a time of severe drought in Utah, and 1934 was the worst in terms of fire-fighting hours logged by the CCC—nearly twelve thousand man-days, more than one-fourth the total fire time for the full nine years. The year 1936 featured another seriously dry summer, and the CCC crew near Milford spent ten days on the three-thousand-acre Wah Wah Mountain fire, one of the largest fires ever fought in Utah.

The following winter of 1936–37 saw heroism become commonplace as Utah experienced one of her worst winter seasons. Operating in what many people considered the coldest weather in Vernal history, CCC crews from the Division of Grazing camp worked around the clock for several days in early January 1937 in temperatures of thirty and forty degrees below zero clearing roads for school buses and for mail and coal deliveries, hauling feed on sleds for thirty-five miles to save starving sheep, and rescuing a sick and bedfast family who had not had a fire for thirty-six hours. In southern Utah, local stockmen requested help from a CCC camp in St. George to try to get feed to herds of cattle and sheep, as well as to people. In eight days of continuous travel, the relief caravan of eight CCC and four private trucks led by an R-5 caterpillar tractor battled snowdrifts for fifty-two miles to Little Tank in the Arizona Strip with twelve tons of cottonseed cake and grain. The situation was grim all across southern Utah.

In addition to regular work projects that benefited the mountains and deserts, the CCC also created good public relations by participating in community work of a volunteer nature; this included projects at Pleasant Grove elementary school, St. George city park, and a small earth-and-rock dam to create an artificial lake 1,000 feet long for the Boy Scouts at Camp Kiesel near Ogden. Enrollees at the American Fork camp worked with local Mormon youths preparing the grounds and planting lawns at Mutual Dell, an LDS campground in American Fork Canyon. In cooperation with Brigham Young University, enrollees installed 5,000 feet of pipe in a new sprinkling system at Aspen Grove. Opening a Forest Service camp in Sheep Creek Canyon in Utah’s northeast corner brought a new way of life to the residents of Manila and the surrounding area; the camp had the only newspaper, telegraph, and doctor in the county.

In addition to the fences, trails, phone lines, roads, and bridges that had been constructed; in addition to the acres of land that had been replanted, terraced, or reseeded; and in addition to the fire-suppression and rescue work that had been carried out by CCC crews, their presence brought direct financial benefits to the state. Enrollees received wages of thirty dollars monthly, of which twenty-five dollars was sent home to their families, while the young men were allowed the remaining five dollars to spend on themselves through the month. More than $125,000 a month thus was pumped into the state’s economy through the wages of the Utah enrollees and LEMs alone. Community leaders and CCC officials estimated that a community would benefit financially by $50,000 to $60,000 every year a camp was in the vicinity. Utah merchants profited from government contracts for lumber, equipment, and foodstuffs. The Federal Security Agency estimated that by the time active operations came to a halt in the summer of 1942, the CCC had spent $52,756,183.00 in the state, and Utah ranked seventh in the nation in CCC expenditures per capita.

With the beginning of World War II, the Great Depression came to an end and the CCC folded in July 1942. The army officers in charge of the camps were transferred to military assignments; most of the camp personnel either entered the armed services or became involved in defense work. The Salt Lake Tribune bade farewell to the CCC in an editorial of 3 July 1942 in which thanks were expressed for the physical accomplishments and recognition granted for the human achievements as well: “More than all else it aided youth to get a new grip on destiny and obtain a saner outlook on the needs of the nation. . . . The CCC may be dead but the whole country is covered with lasting monuments to its timely service.”