Miriam B. Murphy

History Blazer, December 1995

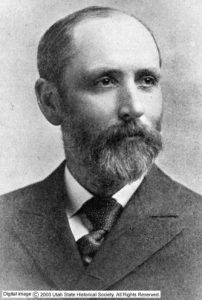

Clarence Allen, 1852–1932, Utah Congressman

In November 1895 Utahns elected Clarence Emir Allen, the Republican candidate, as their first congressman. He took his seat in the House on January 7, 1896, some days before the new state’s two senators, Frank J. Cannon and Arthur Brown, were elected by the legislature. Although Utah had been represented in Congress during the territorial period by an elected, but nonvoting, delegate, Allen was the first Utah representative with full congressional privileges.

Emir, as he preferred to be called, was born on September 8, 1852, in Girard, Pennsylvania. He worked on his father’s farm and attended local schools, but unlike most farm boys of that time he was college bound. He attended Grand River Institute, a college prep school, and Western Reserve University in Ohio, graduating with Phi Beta Kappa honors in 1877. Despite his scholarly achievement, he was more widely known for introducing the curve ball in Ohio as pitcher for the highly successful Western Reserve baseball team. He claimed that a Pittsburgh player had showed him how to throw it. Allen’s physics professor, who doubted that such a ball could be thrown, reportedly came out to the field to see it with his own eyes. After graduation Emir began teaching classics at Grand River Academy and married Corinne Tuckerman. They were the parents of six children, one of whom, Florence, became the first woman appointed judge of a federal appellate court.

In 1881 Allen, who was ill with tuberculosis, moved to the drier climate of Salt Lake City where he had been offered a teaching job at the Salt Lake Academy, a Congregational school. His wife and children joined him when he decided to remain in Utah. Before long Allen began his association with Utah mining. According to a 1921 interview, Allen “went to Bingham with Liberty E. Holden, who offered me a job as assayer. I wasn’t an assayer, but there was no job so big that I couldn’t learn. Someone showed me how to regulate the furnace and how to weigh….In my spare time I went through the mines with the superintendent, asking questions, and after assuming the responsibilities of the pay-roll and the boarding house, I finally became general manager of the Holden properties known as the Old Jordan Mining & Milling company and the Galena Mining company. That was in the days of the carbonates, lead and silver, when copper was not being considered.” Allen continued his mine management career, eventually taking “charge of all the mines and quarries of the [United States Smelting, Refining & Mining] company throughout the intermountain country.”

Meanwhile, Allen became interested in politics. He served in the territorial legislatures of 1888, 1890, and 1894. In 1892 he was the Liberal party nominee for delegate to Congress. In 1893 he was admitted to the Utah Bar, but his practice was evidently not as successful as his other enterprises. He told a reporter, “I had a lot of probate work, but I barely made a living….” Given his mining interests, it is not surprising that Allen aligned himself with the silver cause. As a delegate to the Republican National Convention in 1896 he was one of those who walked out of the St. Louis convention when the gold standard was adopted. He backed William Jennings Bryan, the Democratic nominee for president, rather than McKinley, “because there has never been any doubt about my stand on silver.”

Allen and his wife, also college educated, were both ardent supporters of public education. Allen is credited with authoring a bill passed by the territorial legislature in 1890 that provided for free public schools for students age six to eighteen. Some have called him the “Father of Utah’s Free Schools.” His wife’s efforts were directed toward parent involvement in the schools and free public libraries.

A quarter-century after his service in Congress, Allen recalled two votes he considered significant. He worked to secure passage of Congressman Sperry’s bill to establish free rural mail delivery, and he voted against granting railroad baron Collis P. Huntington a $200 million, 99-year loan for the Central Pacific. He voted against the CP loan, he said, because “it was a time when many persons thought the United States treasury had been created expressly for their needs.”

At age 70 and recently retired as general manager of U.S. Smelting, Refining & Mining Company, Allen told a reporter that his one regret was that he had never been able to fulfill his youthful dream of going to sea. “As near as I can figure out my ancestors were all pirates,” he said, and then added, “I know that some of them were ‘rum runners’ from the West Indies in the early days of Rhode Island.” Still, for a man who was so ill from tuberculosis that he was reportedly carried on a stretcher to his first lodging in Salt Lake City, Allen seems to have accomplished a great deal. He died on July 9, 1932, in Escondido, California. His ashes were returned to Utah for burial in Salt Lake City’s Mount Olivet Cemetery.

See Ben Hite, “How I Began Life: Clarence E. Allen,” in Deseret News, December 24, 1921; Allen Kent Powell, ed., Utah History Encyclopedia (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1994), Wain Sutton, ed., Utah: A Centennial History (New York, 1949); Jeanette E. Tuve, First Lady of the Law: Florence Ellinwood Allen (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1984).