Leonard J. Arrington

Utah History Encyclopedia, 1994

The establishment of settlements in Utah took place in four stages. The first stage, from 1847 to 1857, marked the founding of the north-south line of settlements along the Wasatch Front and Wasatch Plateau to the south, from Cache Valley on the Idaho border to Utah’s Dixie on the Arizona border. In addition to the settlement of the Salt Lake and Weber valleys in 1847 and 1848, colonies were founded in Utah, Tooele, and Sanpete valleys in 1849; in Box Elder, Pahvant, Juab, and Parowan valleys in 1851; and in Cache Valley in 1856. Settlements in all of these “valleys,” as early settlers called them, multiplied with additional immigration throughout the 1850s.

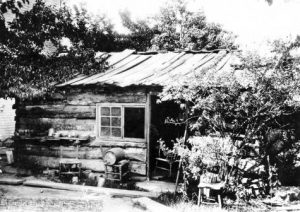

Osmyn Deuel residence, first house in Salt Lake

The first in this southward extending chain of settlements was Utah Valley, immediately south of Salt Lake Valley, which was settled by thirty families in the spring of 1849. Within a year the population had grown to 2,026 people, and the foundation had been laid for a settlement on each of the eight streams in the valley.

Later in 1849, fifty families were called to settle Sanpete Valley, south of Utah Valley, where a nucleus for many other settlements was also established.

Still later in 1849, an exploring party of fifty persons was outfitted to determine locations for settlement between the Salt Lake Valley and what is now the northern border of Arizona, some 300 miles south. Over a three-month period the expedition covered approximately 800 miles, keeping a detailed written record of the topography, areas for grazing, water, vegetation, supplies of timber, and, in general, favorable locations for settlements and forts.

The expedition’s report was quickly put to use. Additional settlements were made in Utah and Sanpete valleys during the fall of 1850, and in November of the same year a large group was sent to colonize the Little Salt Lake Valley in southern Utah. During the next year settlements were made in Juab Valley in central Utah, and still other settlements in Utah, Sanpete, and Little Salt Lake valleys. Within three years after the exploring party’s return, Brigham Young had sent colonists to virtually every site recommended by the expedition.

An important colony in southern Utah was at Parowan. This settlement served the dual purpose of providing a half-way station between southern California and the Salt Lake Valley and of producing agricultural products to support an iron enterprise. Near present-day Cedar City, the exploring party had found a mountain with iron ore, and close to it thousands of acres of cedar which could be used as fuel. Following a “call” in July 1850, a company of 167 persons was constituted in December and sent, complete with equipment and supplies, to Parowan to plant crops and prepare to work with the pioneer iron mission established at Cedar City later in the year. Ultimately, the colony was the nucleus of a dozen settlements made in the region in the early 1850s.

All told, ninety settlements were founded in what is now Utah during the first ten years after the entry into the Salt Lake Valley in July 1847, from Wellsville and Mendon in the north to Washington and Santa Clara in the south. The founding dates of communities settled in these years which eventually became important population centers are Salt Lake City (1847), Bountiful (1847), Ogden (1848), West Jordan (1848), Kaysville (1849), Provo (1849), Manti (1849), Tooele (1849), Parowan (1851), Brigham City (1851), Nephi (1851), Fillmore (1851), Cedar City (1851), Beaver (1856), Wellsville (1856), and Washington (1856).

Although there were many variations, the colonizing effort took one of two main forms: direct or nondirected. Colonies that were directed were planned, organized, and dispatched by leaders of the LDS church. There was preliminary exploration of the area by companies appointed, equipped, and supported by the LDS church; a colonizing company was organized and persons appointed to constitute it, and a leader appointed; and instructions were given by church leaders on the “mission” of the colony—to raise crops, herd livestock, assist Indians, mine coal, and/or serve as a way station for groups on their way to and from California. In cooperative ventures the colonists located a site for settlement, apportioned the land, obtained wood from the canyons, dug diversion canals from existing creeks, erected fences around the cultivable land, built a community meetinghouse-schoolhouse, and developed available mineral resources, if any. Their homes were built near each other in what was called a Mormon fort—Mormon village pattern of settlement. This enabled them to enjoy a healthy social life, with dances each Friday evening, and occasional locally produced vocal and instrumental recitals, plays, and festivals. Ward schools were held each winter and at Sunday School. The women’s Relief Society, young people’s groups, and worship services met each week.

Nondirected settlements were those founded by individuals, families, and neighborhood groups without direction from ecclesiastical authority. Most of the communities along the Wasatch Front were of this type. As the land in established communities was settled, and the available water preempted, young men, upon their marriage, would look for another place to locate. In addition, an average of about three thousand immigrants came into the Salt Lake Valley each summer and fall—and they immediately needed a place to live. Also, there were always adventurous souls who wanted to try a new situation, or who wanted to leave a village. Although LDS officials did not launch nondirected settlements, they encouraged them, sometimes furnished help, and quickly established wards when there were enough people to justify them.

During the second decade after the initial settlement, 1885–67, the threat to the people caused by the approach of the Utah Expedition of General Albert Sidney Johnston in 1857 led Mormon leaders to “call in” all colonists in outlying areas, including San Bernardino, California, and Carson Valley, Nevada, as well as missionaries from all over the world. Land had to be found for them to settle, as well as for the 3,000 or more immigrants who continued to arrive each summer and fall from Great Britain, Scandinavia, and elsewhere. During the ten years after the Utah War, 112 new communities were founded in Utah. New areas opened up for settlement included Bear Lake Valley and Cache Valley in the north; Pahvant Valley and part of Sanpete Valley in the center; and the Sevier River Valley, Virgin River Valley, and Muddy River Valley in the south. Expansion within these and older settlements continued until the 1890s. Important cities that were first settled during this period include Logan (1859), Gunnison (1859), Morgan (1860), St. George (1861), and Richfield (1864).

In establishing these new settlements, much attention was paid to the contributions each could make toward territorial self-sufficiency. This is illustrated most strikingly in the Cotton Mission. A number of parties had been sent out from Parowan and Cedar City in the early 1850s to explore the Santa Clara and Virgin river basins and to determine their suitability for producing specialized agricultural products. The reports of these parties seemed to confirm the hope of Mormon leaders that the new region would be able to produce cotton, grapes, figs, flax, hemp, rice, sugar cane, and other much-needed semitropical products. Small colonies were sent to the area in 1857 and 1858, with the result that cotton was grown successfully on a small scale.

The self-sufficiency program which followed the Utah War and the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 led Mormon leaders to greatly expand the southern colonies. In October 1861, 309 families were called to go south immediately to settle in what would now be called “Utah’s Dixie.” Representing a variety of occupations, they were instructed to go in an organized group and “cheerfully contribute their efforts to supply the Territory with cotton, sugar, grapes, tobacco, figs, almonds, olive oil, and such other useful articles as the Lord has given us, the places for garden spots in the south, to produce.” They were joined in 1861 by thirty families of Swiss immigrants, who settled the “Big Bend” land at what is now Santa Clara. Their mission was to raise grapes and fruit to supply the cotton producers.

In 1862 the 339 were strengthened by the calling of 200 additional families, who were chosen for their skills and capital equipment so as to balance out the economic structure of the community, the center of which was at St. George. All told, nearly 800 families, representing about 3,000 persons, were called to Dixie in the early 1860s. At least 300 additional families–upwards of 1,000 persons–were called in the late 1860s and 1870s. The Cotton Mission was not the only phase of the calculated drive toward diversification and territorial self-sufficiency. Three other colonies were established with a similar purpose. The town of Mantua, in Box Elder County, was founded as part of a campaign to stimulate the production of flax. Twelve Danish families were appointed to settle in what was originally called Flaxville, to produce thread for use in making summer clothing, household linen, and sacks for grain. Similarly, the town of Minersville, in Beaver County, was founded for the purpose of working a nearby lead, zinc, and silver deposit. With the encouragement and assistance of the LDS Church, many tons of lead bullion were produced for use in making bullets and paint for the public works. The town of Coalville, in Summit County, was also founded as part of a church mission to mine coal. Soon after the discovery of this coal in 1859, it was being transported to Salt Lake City for church and commercial use. Several dozen persons were called to the region in the spring of 1860; improved roads to connect with Salt Lake City were built; new mines were discovered; and scores of church and private teams plied back and forth between Coalville and Salt Lake City throughout the sixties. These mines were of particular importance because of the increasing scarcity of timber in the Salt Lake Valley.

During the third decade, 1868–1877, a total of ninety-three new settlements were established in Utah; important communities included Manila, in the northeastern corner of the state (1869); Kanab in southern Utah (1870); Randolph in the mountains east of Bear Lake (1870); Sandy (1870); Escalante (1875); and Price (1877). Continued expansion occurred in the Cache and Bear Lake valleys, the central and upper Sevier River area, and on the east fork of the Virgin River. An Indian farming mission was established at what is now Ibapah in western Tooele County. The Muddy River settlements of the 1860s, which were thought to have been in Utah, were found to be in Nevada. When Nevada demanded back taxes, many of the settlers moved to Long Valley in southern Utah, where they established Orderville in 1875.

An important colonization effort was the movement in 1877 of some of the residents of Sanpete County across the eastern mountains into Castle Valley in Emery County, along the Price River in Carbon County, the Fremont River in Wayne County, and Escalante Creek in Garfield County. Other important new colonies were founded in such unlikely spots as the San Juan County in southeastern Utah, Rabbit Valley (Wayne County) in central Utah, and remote areas in the mountains of northern Utah. Some of these were founded in the same spirit, and with the same type of organization and institutions, as those founded in the 1850s and 1860s: the colonies moved as a group, with church approval; the village form of settlement prevailed; canals were built by cooperative labor and village lots were parceled out in community drawings. Some of the colonies were given tithing and other assistance from the LDS church.

The prime problem of the 1870s was overpopulation. A new generation had grown up and had to find the means of making a living. Some worked in mines, some worked on railroads still under construction, and some migrated to Idaho, Colorado, Nevada, Wyoming, and Arizona.

In the remaining years of the nineteenth and early years of the twentieth century new colonies were founded in a few places that could be irrigated: the Pahvant Valley in central Utah (Delta, 1904); the Ashley Valley of the Uinta Basin in northeastern Utah (Vernal, 1878); and the Grand Valley in southeastern Utah (Moab, 1880). But most of these “last pioneers” had to look for a home in surrounding states where land was still available—Nevada, Oregon, Idaho, Wyoming, New Mexico, and Arizona—or even Alberta, Canada, and northern Chihuahua and Sonora in Mexico. There was no longer the mobilization by ecclesiastical authorities of human, capital, and natural resources for building new communities that had characterized earlier undertakings. The migrations were mostly sporadic—unplanned by any central authority. However, two colonizing corporations organized with ecclesiastical participation were the Iosepa Agricultural and Stock Company, which founded a Hawaiian colony in Skull Valley in 1889; and the Deseret and Salt Lake Agricultural and Manufacturing Canal Company, also established in 1889 to promote settlement in Millard County. The church assisted in these companies financially, held an important block of stock in each, and assured that they would be managed for community purposes.

Another factor in the decline of colonization, particularly after 1900, was the abandonment of the concept of “the gathering,” under which converts were urged to gather to “Zion” to build the Kingdom of God in the West. Converts were now urged to stay put and build up Zion where they were.

All told, some 325 permanent and 44 abandoned settlements were founded in Utah in the nineteenth century. Some of these settlements, however, did not survive the mechanization of agriculture, modern transportation, and the shift of rural population to urban communities that occurred after the Depression of the 1930s. Colonization since World War II has consisted almost entirely of building suburbs around the larger cities.

See: Milton R. Hunter, Brigham Young the Colonizer (1940); Leonard J. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter Day Saints, 1830–1900 (1958); Eugene E. Campbell, Establishing Zion: The Mormon Church in the American West, 1847–69 (1988); Joel E. Ricks, Forms and Methods of Early Mormon Settlement in Utah and the Surrounding Region, 1847 to 1877 (1964); Wayne L. Wahlquist, ed., Atlas of Utah (1981); Richard Sherlock, “Mormon Migration and Settlement after 1875,” Journal of Mormon History 2 (1975); and Leonard J. Arrington, “Colonizing the Great Basin,” The Ensign 10 (February 1980).

Further Reading:

Cartography and the Founding of Salt Lake City by Rick Grunder and Paul E. Cohen