Thomas G. Alexander

Utah, the Right Place

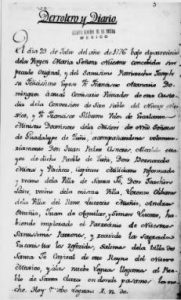

First page of the journal kept by Fathers Dominguez and Velez de Escalante of their 1776-77 expedition through Utah.

Much better known than the Rivera expedition, the travels of Fathers Francisco Atanasio Dominguez and Silvestre Velez de Escalante have left the name of the latter on a number of Utah sites. Utahns did not honor Dominguez, the expedition’s leader, with site names until the bicentennial of their trek in 1976.

Both Dominguez and Escalante enjoyed the advantages of good connections. A native of Mexico, Dominguez received a commission from his Franciscan superiors as a canonical visitor in 1775 and proceeded to inspect the New Mexico missions, evaluate the lives of the frontier padres, and assess the value of the Santa Fe archives that Pueblo Indians had ravaged in the 1680 revolt. He called upon Escalante to assist him in his other task: the search for an overland route to the recently established settlement at Monterey.

By 1776, Escalante, who was born in Spain, had already lived in New Mexico for some time. Ministering to the needs of Christian Indians at Zuni, he also visited the Hopi villages where he found clans of people he called “wretched infidels” flaunting Christian custom by dancing naked and rejecting conversion.

Ordered to Santa Fe to discuss the detail of the Monterey expedition,

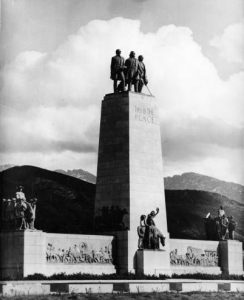

This Is the Place Monument, Father Escalante. Courtesy–Utah State Archives. Gray–Photographer. Digital Image © 2008 Utah State Historical Society.

Escalante met with Dominguez, and the two of them talked with Governor Don Pedro Fermin de Mendinueta. The three feared opening a route directly to the northwest since they believed that the Chirumas, a reputedly cannibalistic tribe, might thwart their progress. Since neither priest wanted to provide the Indians with a brown-garbed lunch, they decided to take a circuitous route through the lands of the relatively friendly Utes.

They planned to depart on July 4, 1776, but had to postpone when events intervened. A Comanche attack on La Cienaga led to Escalante’s assignment as chaplain of a punitive expedition. Following the expedition, Escalante had to go to Taos on business. While there, a severe pain in his side?probably the result of a recurrent kidney ailment?forced him to bed. The diseased kidneys eventually killed him at the age of thirty in 1780.

The two padres and the governor had second thoughts about the expedition when they learned that Fray Francisco Garces had already blazed a trail from Mission San Gabriel near present-day Pasadena, California, by way of the Gulf of California to the Hopi villages in early 1776. Garces wrote to Escalante about his route, and since the “Trails Priest” had, in effect, opened a path from the Pacific Coast to Santa Fe, the two padres considered abandoning their project.

A meeting with Fermin de Mendinueta, however, led to an agreement to make the expedition anyway. The Spanish still had only a vague idea of the lands of Utah, and the stories of settlements of Europeans and unconverted Indians continued to circulate. Even if they failed to reach Monterey, the three principals agreed that the two Franciscans could provide useful ecclesiastical and political information on the country to the north.

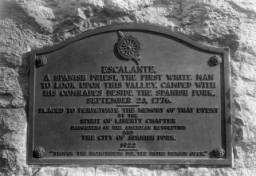

Escalante Expedition Marker

Leaving Santa Fe on July 29, the two friars took a party that eventually included twelve Spanish colonials and two Indians. They recruited eight Spaniards in New Mexico and El Paso and four in southwestern Colorado. They also induced two Timpanogots from Utah Valley, whom they found at a Ute village in western Colorado, to help guide them.

Five of the recruits proved most helpful. These included Bernado Miera y Pachecho, Don Juan Pedro Cisneros, Andres Muniz, and the two Timpanogots, Silvestre and Joaquin. Miera, a retired military engineer who lived in Santa Fe, drew an influential map of the region, recommended sites for presidos, and provided measurements of latitude for the party. Don Juan, alcalde (chief administrative officer) of Zuni, offered valuable judgments as the party progressed. Muniz, an interpreter fluent in the Ute language, had accompanied Rivera on a 1775 expedition to the Gunnison River. Silvestre, a leader in the Utah Valley settlement, guided the party as far as his home. Though only twelve, Joaquin helped guide the party through its entire journey, the only Utah native to do so.

Throughout August, they crossed familiar territory. Muniz had passed through the region before, and Spanish traders and colonists had bartered and boarded with the Utes in western Colorado as well. On September 12, the party crossed what would later become the Utah border near the present-day quarry in Dinosaur National Monument. By this time, they had ventured into lands unknown by the Spanish and placed their lives in the capable hands of Silvestre and the youthful Joaquin.

Having long since outflanked the dreaded Chirumas by their northward march through western Colorado, they pressed westward into Utah. Following Silvestre and Joaquin toward their homeland in Utah Valley, the party crossed the Green River and ascended the Duchesne and Strawberry Rivers. Passing from the Uinta Basin into the drainage of Diamond Fork, they descended to the Spanish Fork River. Nearing Utah Valley, they left the river bank to climb a high prominence near the present-day Spanish Oaks Golf Course from which they gained their first glimpse of the Timpanogots’ home.

Here, they found a terrestrial paradise inviting Spanish settlement. Abundant water, pasturage, croplands, game, fish, fowl, and friendly Timpanogots greeted them. They found ample timber and firewood in the surrounding mountains, and they found the Timpanogots, thriving on fishing, hunting, and gathering. Anticipating that the valley could hold a population as large as that currently living in New Mexico, they promised the Timpanogots, then the largest concentration of people in Utah, that they would return, possibly within a year.

In the meantime, leaving Silvestre in Utah Valley, they induced another Timpanogot, whom they named Jose Maria, to guide them, and they left with Joaquin, treading southwestward on a route approximately parallel to present-day Interstate 15. Throughout the journey, Miera kept himself busy estimating their latitude by shooting the north star with a quadrant. Miera’s observations generally reckoned their location farther north than they actually were. For instance, had Miera’s September 24 estimate of 40o 49′ in Utah Valley had been accurate, the party would actually have been somewhere near Sandy in the Salt Lake Valley.

With Miera’s observations, they believed that they had to travel in a southwesterly direction to reach Monterey, which lay at about 36o 30′ north latitude. Pressing on, they followed the route now marked by I-15 into Pahvant Valley, where they moved southwestward into the desert toward Pahvant Butte and the current Clear Lake Waterfowl Refuge. Continuing southwestward, they suffered a setback just north of present-day Milford. Frightened by a scuffle between Don Juan and his servant Simon Lucero and increasingly homesick as the party moved away from Utah Valley, Jose Maria deserted in the early morning of October 5. Later that same day, a heavy snowstorm imprisoned the party in camp. After the storm abated, they pressed on, sloshing through the snow and mud with great difficulty.

Recognizing that an early winter boded ill for their expedition, Dominguez and Escalante proposed to return to Santa Fe by way of the Havasupai and Hopi villages in northern Arizona. However, Miera and two others in the party dissented, so midway between Milford and Cedar City, the padres agreed to leave the expedition’s fate in God’s hands by casting lots. After God dictated a return to Santa Fe, the party faced the added problem of recrossing the Colorado River. Stymied by the rugged walls of the Grand Canyon, they eventually found a crossing somewhat north of the Arizona border on a trail now covered by Lake Powell’s Padre Bay. Crossing much farther east than they had anticipated, the party pressed on to Oraibi instead of first reaching Havasupai. Once again in familiar territory, they arrived in Santa Fe on January 2, 1777, after a journey of more than 1,700 miles.

The results of the Dominguez-Escalante expedition were virtually all unintended. In spite of the padres’ glowing description of Utah Valley, Utah remained on the northern fringes of the Spanish and Mexican Empires,

Escalante Expedition Marker Spanish Fork, Utah 1922

unsettled by these Hispanic peoples. After the missionaries had returned, however, traders benefited from the trails they and Rivera had discovered. The German geographer Alexander Von Humboldt later found the Dominguez-Escalante journal. Publishing references to it, Humboldt left out Dominguez’s name in the process, and he drew a map based on Miera’s.

Humboldt’s work came to the attention of American path marker John C. Fremont. He commented on the padres’ journal in his report of the 1843-44 expedition that took him to Utah. Fremont also named the Spanish Fork River in honor of the Hispanic explorers. From Fremont’s writings, the Mormons who read the report knew of the Spanish explorations.