Miriam B. Murphy

History Blazer, October 1995

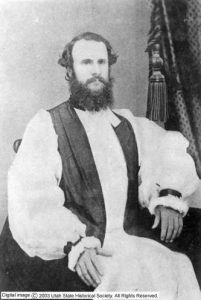

Daniel S. Tuttle was the first Episcopal Bishop of Utah and influential in starting the St. Mark’s grammar school, St. Mark’s Hospital.

May 5, 1867, is a date of special significance for Utah Episcopalians. On that date the first Episcopal service was held in Independence Hall in Salt Lake City.

The Right Reverend Daniel S. Tuttle had been elected Episcopal missionary bishop of Montana, with jurisdiction over Utah and Idaho, in October of 1866. He had been four months short of 30, the minimum age for consecration, and while waiting until that time he recruited missionaries to work with him in the West. His trailbreakers, the Reverend George W. Foote, Bishop Tuttle’s brother-in-law, and the Reverend Thomas W. Haskins, a deacon directly out of seminary, preceded the bishop to Utah by two months.

A cordial welcome greeted the two Episcopal clergymen. Warren Hussey, a Salt Lake banker, had written to Bishop Tuttle in March of 1867 offering financial and moral support, saying “There is no other church in operation here now but the Mormon. The Catholics will be here during spring or summer, and probably the Methodists; and the first here will get most support.” The Sunday School that had been organized by the Reverend Norman McLeod, the Congregationalist chaplain at Camp Douglas, was meeting in Independence Hall under the lay guidance of Major Charles H. Hempstead, the district attorney. McLeod remained in the East after the murder of Dr. J. King Robinson, who had likewise been associated with the Sunday School, and Hempstead lost no time in turning the “Union Sunday School” over to the Episcopalians. About 40 to 60 students attended this school, and under the Episcopal clergy the number steadily rose.

In later years Haskins described his first few days in Utah in a letter. He recalled that the Saturday, May 4, issue of the Union Vedette, the Fort Douglas newspaper, reported the arrival of the two clergymen and the time and place of the first service. That evening, Mrs. J. F. Hamilton, wife of an army doctor, rehearsed the music on the Mason & Hamlin organ at the Hussey’s boardinghouse. Haskins remembered that “the service was conducted without break or omission, as quietly and orderly as it would have been in New York,” and that this opening service keynoted the position and policy of the Episcopal church in relation to the Mormons. He reported this policy as that of “neither antagonizing nor directly assaulting Mormon theology or practice, but planting and maintaining a positive good.”

Early in the week after the first service, an organizing meeting was held in the banking house of Hussey, Dahler & Company. On the committee then appointed were a Roman Catholic, a Methodist (Mr. Hussey, who was later confirmed in the Episcopal church and was the first senior warden at St. Mark’s Parish), and an apostate Mormon (Thomas D. Brown). Among the first contributors and regular attendants to the Episcopal services were Jews in the community. Evening adult instruction classes began immediately, and on his arrival Bishop Tuttle found 11 persons awaiting confirmation, a thriving Sunday School, and an operating grammar school of 16 students. Within a week the latter number had risen to 35.

Immediately upon their arrival, Foote and Haskins were besieged by demands from non-Mormons and Mormons alike for a grammar school, and on July 1 the two clergymen opened the first non-Mormon day school in Utah in a rented adobe building located on Main Street between Second and Third South streets. Board partitions created one room for primary students and another for the grammar department. The curriculum was the basic “three R’s” taught in a free atmosphere that attracted students from the entire community without regard for religion.

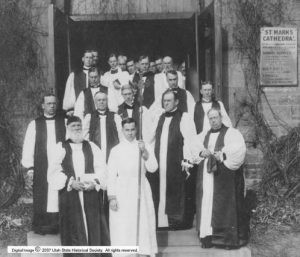

Image shows the men attending a meeting of the Bishops of Province of the Pacific at St. Mark’s Cathedral in 1917. This meeting was held to honor Bishop Tuttle (front left) for 50 years of work in Utah.

Haskins was the first headmaster of St. Mark’s School and taught several hours a day. He wrote that, “The Episcopal Church considers education as the chief handmaid of religion.” Bishop Tuttle seconded this sentiment, adding that, “In Utah, especially, schools were the backbone of our missionary work.” But primarily, the Episcopal schools filled a vacuum in education, where no free public schools were to exist until 1890.

St. Mark’s School expanded into two rented storerooms, then into Independence Hall, and finally in 1873 into its own frame building at about 141 East First South. Episcopal schools were opened from 1870 to 1886 at Ogden, Logan, Plain City, Corinne, and Layton. These functioned until statehood in 1896, when all of the schools had closed, with the exception of Rowland Hall, the girls’ school in Salt Lake City. Tuttle reported that during 1886 some 763 students attended the schools.

Episcopalians take pride in the fact that their church brought the first non-Mormon continuous religious services to Utah and concurrently helped light the lamp of learning and enlightenment in Zion.

See: James W. Beless, Jr., “Daniel S. Tuttle, Missionary Bishop of Utah,” Utah Historical Quarterly 27 (1959).