Yvette D. Ison

History Blazer, June 1995

Fanny Brooks

As the first Jewish family to settle in pioneer Utah, Isabella and Julius Brooks and their children had a lot of adjustments to make when they arrived in Salt Lake City in 1864. But the initial awkwardness soon wore away as the Brooks family became accepted members of the Salt Lake community. Isabella, commonly called Fanny, was largely responsible for her family’s growing prominence in the city. Outspoken and energetic, she ran a boarding house and millinery shop and added a personal touch to her customer service.

Like many immigrants, Fanny had left her home in Germany to find wealth and adventure in America. In 1853, when Julius Brooks returned to his native village after a trip to the United States, his stories of life abroad impressed many of the villagers–most of all 15-year-old Fanny. Determined to accompany him on his next voyage, Fanny approached Julius and eventually won his hand in marriage. The newlyweds boarded a ship to New York City that same year. Fanny later told her children that she entertained the immigrants on the boat with French and German folksongs that she played on her guitar.

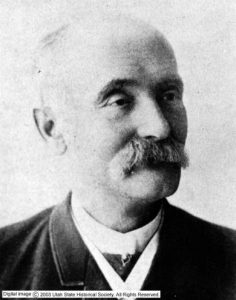

Julius Gerson Brooks

During the next ten years Julius and Fanny traveled throughout the United States. Hearing of business opportunities in the West, they joined a 14-wagon train leaving Illinois on its way to Utah in 1854. On arrival in Salt Lake City, the Brookses stayed with other immigrant parties at Haymarket Square. Their initial stay in Utah was short. After several months the Brookses moved on to California and opened a store in Marysville. Always on the move, the family left after a year and tried new business ventures in San Francisco, Portland, Boise, and small towns along the way. By the time they returned to Salt Lake City they had a family of four children and many stories about life on the road. Tired and travel-worn, they decided to set up a permanent residence in downtown Salt Lake City.

The small adobe house at Third South and Main Street where the Brookses lived was one of the noisiest spots in town. The home was sandwiched between the stables of the Pony Express Company and a gambling saloon. But they quickly adjusted to the unusual environment. Fanny made breakfast for the bull-whackers from a nearby camp. The children became involved in neighborhood activities and even attended an LDS Sunday School until the first Jewish synagogue was built in 1875. Eveline, the oldest daughter, recalled playing jump-rope with Brigham Young’s children.

As the family settled into the community, Fanny decided to establish a boarding house. Julius expanded the dining room to seat up to forty people at a time. The business was successful but soon became threatened by political events in the city. In 1868 Brigham Young announced an anti-gentile edict in which he forbade Mormons from doing business with non-Mormons. Mormon merchants were advised to place an all-seeing-eye sign with the legend “Holiness to the Lord” above their store entrance to indicate their religious affiliation. Non-Mormon merchants quickly began to sell out and leave town.

Angry and unwilling to just pack up and leave, Fanny Brooks demanded a personal interview with Brigham Young. When they met she expressed her concern about leaving a city where she had devoted so much time and effort to its betterment. In response, Young explained that some of the non-Mormon merchants had come to Salt Lake with the aim of running the town. He realized that Fanny and her family were an exception to the rule and promised that she could continue to board Mormon customers in her home. From that day on, the church leader remained friendly with the Brookses and supportive of their Jewish faith. As a symbol of his good will he offered to donate land for a Jewish cemetery in 1869.

Encouraged by the success of the boarding house, Fanny decided to open a millinery shop. Julius purchased the merchandise for the store, and Fanny managed the accounts and ran the store. Julius hired Hiram Parson as a clerk because he knew that his family of seven children was very poor. Fanny adopted an attitude of service. She treated customers well because she knew that personal attention would encourage them to come back. Her daughter Eveline recounted a story that demonstrates her mother’s professional approach. On one occasion, a lady fussed around the store, unable to find a suitable hat. Julius responded to her by saying, “My dear lady, if I had hats to make ugly ladies look pretty, I would be a millionaire and live in New York.” The woman was insulted and about to leave the store when Fanny returned from an errand. She assured the customer that her husband had not been serious and then sold her three hats with the promise that she looked lovely in each.

The Brookses did well with the millinery business. According to Eveline, by the end of the second year the family had earned $40,000 from the shop. In 1879 Julius constructed an elegant European-style shopping mall called the Brooks Arcade. Julius and Fanny spent most of their later years traveling in Europe and visiting relatives and friends. In 1885 Julius died in San Remo, Italy. Fanny continued to run her millinery shop in Salt Lake City. As her health deteriorated, however, she made more frequent trips to her home town of Wiesbaden, Germany. She died there on August 21, 1901, leaving behind a unique legacy as a skilled and determined businesswoman and an active Jewish citizen in the early history of Salt Lake City. Both Julius and Fanny Brooks are buried in the Jewish section of the Salt Lake City Cemetery.

See: Annegret S. Ogden, ed., Frontier Reminiscences of Eveline Brooks Auerbach (Berkeley: Friends of the Bancroft Library, University of California, 1994); Jack Goodman, “Jews in Zion,” in Helen Z. Papanikolas, ed. The Peoples of Utah (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1976); Leon L. Watters, The Pioneer Jews of Utah (New York, 1952).