Deborah Blake

Utah History Encyclopedia, 1994

On 10 May 1869 from Promontory Summit northwest of Ogden, Utah, a single telegraphed word, “done,” signaled to the nation the completion of the first transcontinental railroad. Railroad crews of the Union Pacific, 8,000 to 10,000 Irish, German, and Italian immigrants, had pushed west from Omaha, Nebraska. At Promontory they met crews of the Central Pacific, which had included over 10,000 Chinese laborers, who had built the line east from Sacramento, California.

On 10 May 1869 from Promontory Summit northwest of Ogden, Utah, a single telegraphed word, “done,” signaled to the nation the completion of the first transcontinental railroad. Railroad crews of the Union Pacific, 8,000 to 10,000 Irish, German, and Italian immigrants, had pushed west from Omaha, Nebraska. At Promontory they met crews of the Central Pacific, which had included over 10,000 Chinese laborers, who had built the line east from Sacramento, California.

Actually, the construction crews built several miles of track parallel to each other. The federal legislation chartering the transcontinental project had not provided that the tracks join. There was nothing to prevent each line from continuing to build and thus increase the subsidies it might receive from the federal government. Therefore, Congress acted to set the meeting point at Promontory.

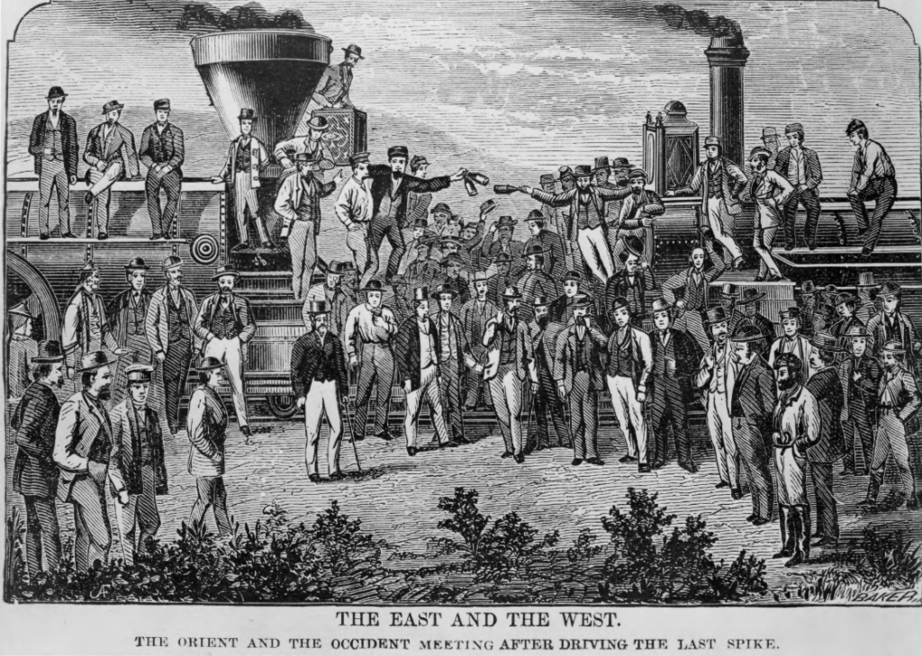

The ceremony that day to mark the completion of the last set of ties and spikes was somewhat disorganized. The crowd pressed so close to the engines that reporters could not see or hear much of what was actually said, which accounts for many discrepancies in the various accounts.

Union Pacific Railroad under construction, Promontory Point, May 10, 1869

Union Pacific’s No. 119 and Central Pacific’s “Jupiter” engines lined up facing each other on the tracks, separated only by the width of one rail. Leland Stanford, one of the “Big Four” of the Central Pacific, had brought four ceremonial spikes. The famed “Golden Spike” was presented by David Hewes, a San Francisco construction magnate. It was engraved with the names of the Central Pacific directors, special sentiments appropriate to the occasion, and, on the head, the notation “the Last Spike.” A second golden spike was presented by the San Francisco News Letter. A silver spike was Nevada’s contribution, and a spike blended of iron, silver, and gold represented Arizona. These spikes were dropped into a pre-bored laurelwood tie during the ceremony. No spike represented Utah, and Mormon church leaders were conspicuous by their absence.

At 12:47 P.M. the actual last spike—an ordinary iron spike—was driven into a regular tie. Both spike and sledge were wired to send the sound of the strikes over the wire to the nation. However, Stanford and Thomas Durant from the Union Pacific both missed the spike. Still, telegraph operator Shilling clicked three dots over the wire: “done.” Meanwhile, with an unwired sledge, construction supervisors James H. Strobridge and Samuel R. Reed took turns driving the last spike.

For several weeks Promontory continued to be a town of tents and crude shacks. The land speculators, petty merchants, saloon keepers, gamblers, and prostitutes who had followed these tent cities stayed only as long as there were workers to entice. But, unlike many of these “hell on wheels” camps, Promontory never became the site of a permanent city.

In 1901 the Central Pacific steam engine “Jupiter” was scrapped for iron. The Union Pacific’s No. 119 was scrapped two years later. The 1903–04 construction of the Lucin Cutoff siphoned most of the traffic from Promontory’s “Old Line.” The last tie of laurel was destroyed in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. One of the supporting ties had been used as a roof beam in a barn that Edgar Stone, the fireman on the Jupiter, had built in North Ogden. Only the “Last Spike” remained—ensconced at Stanford University.

In 1942 the old rails over the 123-mile Promontory Summit line were salvaged for war efforts in ceremonies marking the “Undriving of the Golden Spike.” Artifact hunters picked over the area for ties and materials. The event of the completing of the transcontinental railroad, which some historians had compared in significance to the Declaration of Independence, seemed to fade from public consciousness.

However, a memorial marker of the “Last Spike” had been placed along the

Copy of an old woodcut showing juncture of first transcontinental rail line at Promontory, Utah, May 10, 1869. Central Pacific’s “Jupiter” at left, and U.P.’s No. 119. The woodcut appeared in Crofutt’s “New Overland Tourist Guide Book” 1878-79.

right-of-way in 1943, and in the years after World War II local residents began marking the event. In the 1948 reenactment of the driving of the last spike, miniature locomotives were furnished by the Southern Pacific. In 1951 a monument to the event was dedicated and placed in front of the Union Station in Ogden. In 1957 Congress established a seven-acre tract as the Golden Spike National Historic Site. Bernice Gibbs Anderson of Corinne organized the National Golden Spike Society in 1959 to promote the site. In 1965 Congress enlarged the site to encompass 2,176 acres and be administered by the National Park Service. That same year Weber County extended the highway from 12th Street to Promontory, which made access to the site easier.

The enthusiasm to mark the centennial of the transcontinental railroad grew during the next few years. Searches were made for old engines, a commission to plan the reenactment was organized, the Golden Spike Monument was moved 150 feet to the northwest, and the National Park Service began the reconstruction of the two railroad grades, the lines of track, and two telegraph lines, as well as switches and siding connections.

This is the pulling of the golden spike by L. P. Hopkins, left, division superintendent, Southern Pacific Railroad, Herbert B. Maw, Governor of Utah and E. C. Schmidt, assistant to the president of the Union Pacific Railroad. Digital Image © 2008 Utah State Historical Society.

The engines used in the 1969 ceremonies were modified to resemble the originals. From 1970 to 1980 the annual reenactment used two vintage locomotives on loan from Nevada. But, in 1980, with water from Liberty Island in New York Harbor and Fort Point in San Francisco Bay, two replica steamers constructed by Chadwell O’Connor Engineering Laboratories of Costa Mesa, California, were dedicated. Built with $1.5 million in federal funds, these were the first steam engines constructed in the United States in twenty-five years. They now run daily from May to August and from Christmas to New Year’s Day. Park Service personnel at the Golden Spike Information Center, also dedicated in 1980, can direct visitors to walking and driving tours along the old grades, as well as to photo and other exhibits celebrating the transcontinental railroad.

See: Utah Historical Quarterly (Winter 1969).