Miriam B. Murphy

History Blazer, February 1996

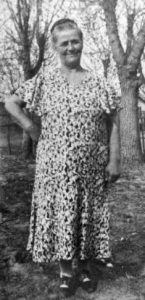

Mrs. Nick Mageras (“Magerou”), midwife to two generations of Greek, Italian, and Slav women in the Magna-Midvale-Tooele area. She was renowned for her folk cures. This photo was used in the book, “The Peoples of Utah” (1976). Digital Image (c) 2008 Utah State Historical Society.

She was the matriarch of the first Greek immigrant families to settle in Midvale, Bingham, and Magna. Most of the men worked in the copper mine and the smelters. Georgia Lathouris Mageras—called Magerou after her marriage—was the midwife who delivered their offspring and provided many other medical services to the community.

She was born in a small village in Greece in the late 1860s. As a child she often took food to her father and brothers who were caring for the family’s goats in mountain pastures beyond the village. One day a woman in labor called to her for help. Following the woman’s instructions, the girl, who was only 14, delivered the baby and thus began her long career as a midwife. Later, Nikos Mageras came to her village to build a bridge and asked to marry her even though her family was too poor to provide the traditional dowry. With Greece in financial and political turmoil at the turn of the century, Nikos left for America in 1902, hoping to earn enough money to send for his growing family. Not until 1909 did Magerou and their children arrive in Utah where Nikos had discovered he had a brother and several cousins working for the Utah Copper Company in Bingham. The family settled in Snaketown west of Magna.

As the young men of the community married picture brides from their native land, Magerou’s services as a midwife were in demand. According to historian Helen Z. Papanikolas, “not only Greek, but Italian, Austrian, and Slavic women called Magerou at all hours. They preferred her to the company doctors.” In all her years of presiding over the birth of children she never lost a mother or a baby. If a birth presented unusual difficulties, however, she insisted on sending for a doctor.

One component of her success was cleanliness. There was no excuse for a home or a person to be dirty, she said, when water and soap were so easily obtained in America. Papanikolas described her at work: “Magerou took care of her women patients with the efficiency of a contemporary obstetrician. While olive oil and baby blankets were kept warm in coal stove ovens, she boiled cloths, kept water hot, cut her fingernails, scrubbed her arms and hands well, and after observing American doctors using alcohol and rubber gloves, she added these to her accoutrements….Small though she was, her voice carried through the neighborhoods, exhorting, shouting, ‘Scream! Push! You’ve got a baby in there, not a pea in a pod!’ Once the baby was born, Magerou gave her entire time to the newly delivered mother….From the backyard she chose the plumpest chicken, simmered broth, stood over the mother forcing her to wash and to dress in a clean house dress, combed her long hair, and twisted it into a knot. For the first time in her life, the woman knew what it was to be pampered.” Husbands, used to ruling the roost, became errand boys running to the store to get whatever the midwife said was needed.

The early 1920s were the busiest for Magerou not only as a midwife but also as a healer because the immigrants, new to American ways, still relied on folk cures, especially for dispelling the Evil Eye, a common complaint not recognized by most doctors. If a child suddenly became lethargic, had an unexpected high fever or whined and cried for no apparent reason, mothers suspected that “someone with the Evil Eye had looked on the child with envy.” Magerou might use three pinches of incense (burned in homes on Saturday to purify them for the Sabbath) or three drops of holy water. Three was a holy number symbolizing the Trinity. She recited the Lord’s Prayer during her ministrations to the ailing.

She treated pneumonia and bronchitis with drinks of hot red wine and powdered cloves or tea and whiskey and mustard plasters applied to the chest, back, and soles of the feet. “Bleeding was a favorite remedy…she used… for almost every ailment, especially infections. In America there was no need to search in ponds for leeches; drugstores sold them.” She was renowned for curing backaches and setting bones. She made a cast from a mixture of powdered resin, egg whites, and clean sheared wool. “Two men owed their legs to her. A Greek baker in Garfield had mashed his knee; the surgeon decided to amputate. The baker left the doctor’s office and went to Magerou. She used her remedies and ‘in a week the baker was walking about.’ A justice of the peace had crushed his leg at Mercur and sought the midwife’s help rather than submit to an amputation. Again she was able to save a leg.”

Over the years the Mageras family moved several times: to Murray, Tooele, and back to Magna. Wherever she lived patients sought her out, some traveling great distances for help. She worked until her late seventies. Her husband died in 1946, and she died in 1950 at the age of 83. She had lived through many difficult times and tumultuous events. The immigrant generation of Greeks and other southern Europeans faced discrimination in their daily lives, including attacks by the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s and venomous editorials in newspapers. Through it all Magerou “had faith in time’s solution to problems. The many pictures of her show a smiling, serene woman appearing much younger than she was. . . . She was stoic over the deaths of her own infants and family reverses. She endured without knowing that she did. The feast days of her church gave her life order and happiness.” She remains a symbol of the color and uniqueness of Greek immigrant life in Utah.

Source: Helen Zeese Papanikolas, “Magerou, the Greek Midwife,” Utah Historical Quarterly 39 (Winter 1970).