W. Paul Reeve

History Blazer, August 1995

Hole-in-the-Rock

In 1879 when a group of Mormon pioneers began the now famous Hole-in-the-Rock expedition, the San Juan region of southeastern Utah was one of the most isolated parts of the United States. The rough and broken country is characterized by sheer walled cliffs, mesas, hills, washes, slickrock, cedar forests, and sand. Certainly the ruggedness of the country accounts for its colonization coming so late in the Mormon settlement effort. The Mormon hierarchy’s need to improve relations with the Indians, ensure Mormon control of the area, open new farmlands for cultivation, and build a springboard for future colonies to the east, south, and north provided the impetus behind church president John Taylor’s “call” for colonizing mission to the San Juan. Those who answered his plea demonstrated remarkable faith, courage, and devotion to the Mormon cause and persevered even when confronted with the challenges of southeastern Utah’s physical environment. They cut a wagon passage through two hundred miles of that inhospitable corner of the state and ultimately succeeded in establishing permanent communities in its remote expanses.

A total of 236 individuals from sixteen different southwestern Utah villages formed the mission. The majority were from three Iron County towns: Parowan, Paragonah, and Cedar City. Ignoring other lengthy, but well-established routes, leaders of the mission opted to try a “short cut” by way of Escalante that would take them through almost completely unexplored country. The biggest obstacle along the chosen course was the Colorado River, but according to a scouting report from the summer of 1879 it was passable. The scouts had discovered the Hole-in-the Rock, a narrow slit in the west wall of Glen Canyon. They reported that a road could be built through it leading down to the river. Based upon this recommendation the group began to gather in late November and early December at Forty Mile Spring about forty miles southeast of Escalante. In the meantime, exploring parties returned with negative reports concerning the terrain east of the Colorado, which looked extremely difficult for wagon travel. Unfortunately, snow had already blocked any return to their former homes, and so the group determined to forge ahead.

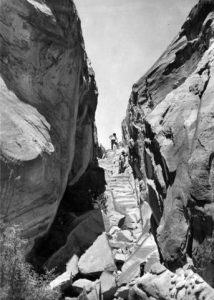

Although challenging, the first sixty-five miles of their journey proceeded with relatively minor difficulties. They formed a base camp at Fifty Mile Spring, about six miles from the Hole-in-the-Rock. From there approximately half of the expedition spent the next month and a half blasting a road through the very narrow crack to allow for the passage of wagons. At the bottom of the steep slope leading to the river the pioneers ingeniously rigged a crib which they piled with logs, brush, fill dirt, and rocks to serve as a “tacked-on” road bed for the outside wagon wheels. Finally the precarious road was completed, and on January 26, 1880, about forty wagons were taken through the Hole-in-the Rock. Elizabeth Morris Decker, in a letter to her parents, wrote a vivid account of the descent to the river: “If you ever come this way it will scare you to death to look down it. It is about a mile from the top down to the river and it is almost straight down, the cliffs on each side are five hundred ft. high and there is just room enough for a wagon to go down. It nearly scared me to death. The first wagon I saw go down they put the brake on and rough locked the hind wheels and had a big rope fastened to the wagon and about ten men holding back on it and then they went down like they would smash everything. I’ll never forget that day. When we was walking down Willie looked back and cried and asked me how we would get back home.”

Even with the Hole-in-the-Rock behind them the colonizers still faced many miles of rugged terrain–primarily solid slickrock and mountains cut by deep gulches—before reaching their destination. Decker described it as “…the roughest country you or anybody else ever seen; its nothing in the world but rocks and holes, hills and hollows. The mountains are just one solid rock as smooth as an apple.” Undaunted the determined pioneers cut dugways and blasted roads through the slickrock, cut a passable trail through the dense cedar forests, and when required made more cribbing for the outside wheels to pass over. Then on the north bank of the San Juan River the weary, hungry, and discouraged travelers faced yet another grueling trial: the solid rock wall of San Juan Hill. According to Charles Redd whose father, Lemuel H. Redd, Jr., drove a horse team up the hill, the steep, slick grade took its toll on the exhausted animals and men. Many of the horses went into “spasms and near-convulsions” as they battled for footholds on the upward climb. When it was all over “the worst stretches [on the hill] could be easily identified by the dried blood and matted hair from the forelegs of the struggling teams.”

The San Juan pioneers reached the present site of Bluff in April 1880 and set to work planting crops, digging ditches, and establishing a new community. Many challenges remained. The San Juan River frequently washed out their

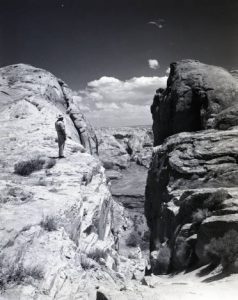

Tourist overlooking Hole-in-the-Rock area.

dams and ditches, and Indian hostilities posed a continual threat. Many of the original group abandoned the hard-won location, while those who stayed were often forced to seek outside employment to survive. Hardships aside, Bluff eventually spawned other colonies in the region, including Verdure, Monticello, and Blanding. These remote southeastern Utah communities owe the ultimate credit for their existence to a tenacious group of Hole-in-the Rock pioneers.

Sources: Allan Kent Powell, “The Hole-in-the Rock Trail a Century Later,” in San Juan County, Utah: People, Resources, and History, ed. Allan Kent Powell (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1983): David E. Miller, Hole-in-the-Rock: An Epic in the Colonization of the Great American West (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1966).