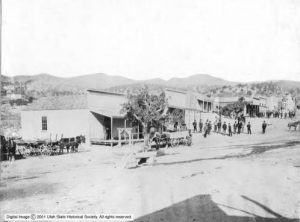

Frisco, Beaver County, ca. 1880, with silver mills and smelters on hill behind town.

Miriam B. Murphy

History Blazer, January 1996

The story of the Horn Silver Mine, one of the great producers in Utah and American mining history, reads like pulp fiction: Two prospectors casually discover a rich ore body, a bankrupt financier promotes the venture, the boomtown of Frisco becomes one of the wildest mining camps in the West with a murder or two every evening, a tough lawman who shoots on sight begins to clean up the town, after producing millions the huge mine collapses, and Frisco becomes another ghost town.

It all started in September 1875 when prospectors James Ryan and Samuel Hawkes, who were working a galena mine in the San Francisco Mining District of Beaver County, tested a huge outcropping they passed each day. They found a solid ore body and immediately staked a claim to it. The two men decided to sell the claim rather than work it, fearing perhaps that the ore body was not as large as it appeared. By the late 1870s the new owners had extracted 25,000 tons of ore with a high silver content. The town of Frisco had sprouted up near the mine, some 17 miles west of Milford. But developing a mine in that remote area, some 175 miles from the nearest railhead, required more financial muscle than was locally available.

Enter Jay Cooke, the financial genius who had come up with the idea of selling federal bonds to pay for the Civil War. In 1870 he was reportedly the richest man in America and the nation’s leading banker. By 1873 he was broke. The Franco-Prussian War and the Panic of 1873 had dealt a fatal blow to his promotion of bonds to construct the Northern Pacific Railroad. Even his mansion near Philadelphia had been taken by creditors. Cooke had never been interested in mining investments, but a friend convinced him to take a look at the Horn Silver Mine in far-off Utah. Following a complicated series of events “Cooke induced the owners to bond the property to him in consideration of his promise to give them railroad connections.” Cooke did not have a dime to put into the venture, but he still had his genius for organizing and promoting. He was able to convince the mine owners and the LDS church to each provide a quarter of the capital needed. The remaining half was guaranteed by Wall Street financier Jay Gould. Within a few years Cooke was again rich, selling his shares in the Horn for an estimated $1 million. Exit Jay Cooke.

By 1879 the United States Annual Mining Review and Stock Ledger was calling the Horn “unquestionably the richest silver mine in the world now being worked.” Frisco fairly buzzed with activity. Two smelters processed ore from the mine, and the company had developed a number of other needed facilities, including charcoal kilns, an iron reflux mine, a telegraph line to Beaver, and several stores in Frisco. Still, smelting on site was difficult and expensive due to the scarcity of fuel, water, and iron ore. With the completion of the Utah Southern Railroad Extension to Frisco on June 23, 1880, ore could be shipped to the Francklyn smelter near Murray, Utah, for processing. During its peak years some 150 tons of ore a day were sent to the Salt Lake Valley for smelting. By 1885 the Horn had produced more than $13 million and paid its shareholders $4 million in dividends. Some of its ore averaged 70 to 200 ounces of silver per ton.

The town of Frisco quickly became a center of vice and crime. Like many a boomtown in the West its streets were lined with saloons (21 according to one count), gambling dens, and houses of prostitution. One writer called it “Dodge City, Tombstone, Sodom and Gomorrah all rolled into one,” noting that murders occurred so often that city officials contracted to have a wagon pick up the bodies and take them to boothill for burial. Eventually Frisco’s reputation had become so tarnished that Marshal Pearson from Pioche, Nevada, was hired to clean up the town. He allegedly told the lawless elements that he did not intend to make arrests. Instead, he planned to shoot on sight anyone he saw breaking the law. He supposedly killed six outlaws on his first night in town.

Then, on the morning of February 12, 1885, after the night shift had come to the surface, the day crew was told to wait because tremors were shaking the ground, and the Horn had experienced several cave-ins previously. Within minutes a massive cave-in closed the main shaft and collapsed tunnels down to the seventh level, shutting off the richest part of the mine. The cave-in was felt as far away as Milford where some windows were reportedly broken. Rain and snow had recently soaked the ground and added tremendous weight to the supporting timbers in the tunnels below. Additionally, the operators, in their hurry to take wealth from the mine as quickly as possible, had not adequately timbered the maze of tunnels. Fortunately, the cave-in occurred between shifts and no one was killed.

In less than a year the Horn was producing again on a limited scale. By 1891 quarterly dividends averaged $50,000, and the “Horn was still one of eight leading silver mines in the United States which, collectively, had produced more than half of the nation’s total silver production value.” The Horn had recovered and continued to produce varying amounts of silver and other metals for a succession of owners for another six or seven decades. But the cave-in had doomed infamous Frisco, once home to several thousand residents and a thriving place of commerce–some of which was even legal.

Sources: Leonard J. Arrington and Wayne K. Hinton, “The Horn Silver Bonanza” in The American West: A Reorientation, ed. Gene M. Gressley (Laramie: University of Wyoming, 1966); Harold O. Weight, “When the Horn Silver Caved,” Westways, February 1952; George A. Horton, Jr., “An Early History of Milford” (M.S. thesis, Brigham Young University, 1957); George A. Thompson, Some Dreams Die: Utah’s Ghost Towns and Lost Treasures (Salt Lake City: Dream Garden Press, 1982)