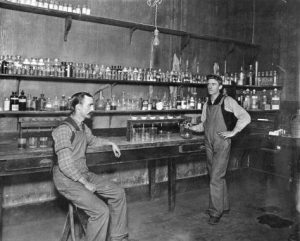

Ontario Mine employees, Park City

Philip F. Notarianni

Utah History Encyclopedia, 1994

Mining for metals, coal, hydrocarbons, and minerals was a vital aspect of Utah’s economic, industrial, political, and social growth and development. The mining industry has touched all aspects of life in Utah and has contributed greatly to the state’s history.

Mormon gold miners participated in the initial discovery of gold in California, and gold dust imported from California between 1848 and 1851 to Utah was processed by Mormon pioneers. But Brigham Young discouraged his people from searching for precious metals because he feared not only the loss of critical manpower to the goldfields but also that mining would distract Mormons from agricultural pursuits and would attract non-Mormons, or Gentiles.

Although early leaders of the Mormon church placed a higher value on agricultural development than on mining for the precious metals, Brigham Young did recognize the need for iron, a metal that was costly to import by wagon from the East. In 1850 Young issued a “call” for an “iron mission” to southern Utah (Iron County), but after four years this effort was abandoned. In the 1860s church leaders encouraged lead and silver mining around Minersville. Brigham Young’s resistance to precious-metal mining began to break down with the coming of the railroad, and Mormons came to dominate the prospecting of such ores in many areas until the economic collapse of the mid-1870s. In the 1880s and 1890s, the decades after Brigham Young’s death in 1877, a number of church leaders including John Taylor, George Q. Cannon, and Joseph F. Smith, became involved in the ownership of silver mines.

The beginnings of commercial mining in Utah are traced to Colonel Patrick E. Connor and his California and Nevada Volunteers who arrived in the Salt Lake Valley in October 1862. Many of these soldiers were experienced prospectors and, with Connor’s blessing and prompting, they searched the nearby Wasatch and Oquirrh mountains for gold and silver. In 1863 the first formal claims were located in the Bingham Canyon area, and this spurred further exploration.

Discoveries soon followed in Tooele County and in Little Cottonwood Canyon (1864). With the development of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 came the transportation network necessary to elevate Utah’s mining efforts from small-scale activity to larger commercial enterprises. Other early mining areas included the Big Cottonwood, Park City, and Tintic districts, along with the West Mountain District, which encompassed the entire Oquirrh mountain range. Mining activity in these regions grew through the 1880s, but, as surface deposits dwindled, the need to mine for mineral sources at depths far beneath the surface necessitated larger amounts of capital, and individual efforts generally gave way to corporate interests. Between 1871 and 1873 the British invested heavily in Utah mining ventures, the most noted being the Emma Mine in Little Cottonwood Canyon, which was rocked with scandal involving unscrupulous mining promotion.

After the Panic of 1893 and the subsequent depression had ended, mining in Utah burgeoned. By 1912, 88 mining districts were listed for the state (between the years 1899 and 1928 the Salt Lake Mining Review listed some 122 districts). Production figures, in terms of total value compiled to 1917, illustrate the successful mining of gold, silver, copper, lead, and zinc in Utah’s three leading mining districts:

Bingham (1865-1917) $419,699,686

Park City (1870-1917) $169,814,024

Tintic (1869-1917) $180,401,804

Other districts listed included Big and Little Cottonwood ($25,722,533), American Fork ($3,895,050), Piute County ($3,679,143), Carbonate ($478,122), Mt. Nebo ($190,762), and West Tintic ($139,018).

Essential to the rapid increase in mine production was the further expansion of transportation facilities, including the competition between the Union Pacific and the Denver and Rio Grande Western railroads, which fostered the completion of spur lines and narrow-gauge district lines. Also essential was the development of mills and smelters needed to make the shipping of ores and concentrates a profitable enterprise. Custom mills and smelters virtually sprang up near many mines, beginning in the 1870s and continuing to the turn of the century. Most of these operations proved ephemeral, lasting only long enough to treat the grades of ore for which they were built. Of more importance was the construction of large smelting plants in the Salt Lake Valley. The erection of these facilities also commenced in the 1870s. In Murray, the Germania and the Hanauer plants functioned into the 1890s. They were purchased by the American Smelting and Refining Company (ASARCO) in 1899. ASARCO also purchased the Mingo smelter, built in Sandy in 1878. By 1902, ASARCO had begun operations treating lead-silver ores in its large plant in Murray.

The Midvale area became another key smelting region. In 1873 the Sheridan Hill smelter was built at West Jordan to treat ores from the Neptune Mine. The Galena smelter, constructed in 1873, treated ores from the Galena and Old Jordan mines at Bingham. It later became known as the Old Jordan Smelting Works. In 1899 the United States Mining Company—later the United States Smelting, Refining, and Mining Company (USSRMCO)—was organized, and in 1902 it completed its large smelter at Midvale. The ASARCO and USSRMCO plants, together with the International Smelting and Refining Company operation in Tooele, became giants on both a state and regional level in the consolidation of the smelting industry.

Utah’s major mining areas were West Mountain (Bingham), Park City, and the Tintic District. Park City flourished with the Ontario, Silver King, Daly-West, Daly-Judge, and Silver King Consolidated mines, among others. From these holdings came mining millionaires such as David Keith, Thomas Kearns, John Judge, and Susanna Emery Holmes (known as the Silver Queen). This newly acquired mining wealth substantially helped to change Salt Lake City’s economic base and its agrarian, rural village character. Palatial mansions began to line South Temple (Brigham Street).

Ontario Mines assay office, Park City, 1900

Samuel Newhouse, mining entrepreneur of the West Mountain and Beaver County (Newhouse) areas in the 1910s, engineered the construction of what was planned as the “Wall Street of the West.” His Exchange Place development on Main Street in Salt Lake City, highlighted by the gateway formed by the Boston and Newhouse buildings, ran perpendicular to the Federal building and signified the presence of non-Mormon influence in the city. The Salt Lake Stock and Mining Exchange (founded in 1908) was located there. Salt Lake City became a regional center for foodstuffs as well as mining implements and machinery. With growth came secondary and tertiary businesses.

Metal mining also sparked population growth in Utah. In addition to introducing new industries and technology, a large amount of labor was needed to work in the mines, mills, and smelters. Mining companies sought this labor at a time when southern and eastern Europeans as well as Japanese were immigrating into the United States as part of the mass migration of the period from the 1890s to the 1920s. The social dynamics associated with immigrant peoples, their interactions, and the communities they formed were crucial accompaniments to mining and as such cannot be separated from the industry itself.

Northern Europeans, such as the Irish, Welsh, and Cornish, arrived in the metal towns first, followed by southern and eastern Europeans, Japanese, and Mexicans. The Chinese, finished with the business of railroad building after 1869, funneled into mining towns such as Park City, where memories of China Town and China Bridge still continue. Mining and smelter towns alike contained varying degrees of ethnic diversity, producing tensions and labor strife. Nativism–antiforeign sentiment, bigotry, and racism–existed in Utah, and erupted most evidently in metal-and coal-mining regions. Unionism attracted these “new immigrants,” as it did others with grievances. Strikes and labor-management relations were an important part of Utah’s industrial history—the celebrated local trial and execution of Joe Hill and the growth locally of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) are but two examples.

Metal mining in Utah, as in other locales, reacted to the vagaries of the economy. Upswings and downturns created periods of optimism and pessimism. The Great Depression of the 1930s affected the industry greatly, causing production to plummet. However, World War II caused the demand for metals to rise, rejuvenating the industry.

Uranium, the “wonder mineral” that became a giant in the 1950s, had been sought in earlier days. The quest for uranium and accompanying minerals has historical roots in Utah, and the industry of the late 1950s and 1960s rested upon prior experience in the fields of prospecting, mining, and processing. The earliest users of uranium ore in Utah were Native Americans who used it for paints. Initial Utah uranium mining began in the 1870s and 1880s on a small scale, with ore shipped to France and Germany in 1884 for use in the forming of salts and oxides as colorants for ceramics and dyes, in the manufacture of glass and pottery, and as aids in photography and steel plating. By 1898 radium had been isolated from the mineral, and carnotite had been found and identified. Radium became known as a “wonder drug.”

The eastern and southeastern regions near the basin margins of the Green, Grand, and Colorado rivers in Utah contain deposits of uranium. In 1898 the Welsh-Lofftus Uranium and Rare Metals Company operated in Richardson, Grand County. The San Rafael deposits were found about fifteen miles southwest of the Green River; and in 1904 ore was located in Wayne County, southeast of the San Rafael Swell. Other areas where uranium was found were west of the La Sal Mountains, south of Richardson, at Mill Creek, north of Moab, at Cold Creek (twenty miles north of Price), and at Temple Mountain.

Market demands grew for vanadium and radium, which are found in uranium. By 1906 nearly 200 tons of uranium were mined annually in Colorado and Utah. World War I sharpened the demand, as vanadium was used as a steel-hardening agent, and radium found a use as an illumination agent for watch faces, compasses, gunsights, and airplane dials. Nearly all the known deposits were located in the United States, and the market demand was high.

Shifting trends affected and altered Utah’s uranium industry. Production slowed during the 1921-22 depression. Of more permanent significance were the rich ore finds of radium in the Belgian Congo in 1923, and of vanadium in Peru. These countries came to dominate the market. Between 1923 and 1940 the production of uranium in Utah and the West proved negligible. However, during the Cold War period of the 1950s and 1960s uranium again reigned as a “wonder metal.” The uranium strikes of the 1950s created another “bonanza” period in Utah mining. Charles (Charlie) Steen reigned as the most well known of the uranium bonanza kings. His palatial home in Moab exemplified this newfound wealth; but Steen’s fortunes also were affected by the economic downturns of the industry.

Gilsonite, a lightweight, glossy black, bituminous asphaltite, is the primary hydrocarbon mined in Utah. It has been mined commercially only in northeastern Utah, where it occurs south of Vernal and Roosevelt in parallel vertical veins that cut across the Uinta Basin. It is believed to be a solid residue of petroleum, and was initially named uintaite in 1885 by W.P. Blako. The mineral was later named in honor of Samuel H. Gilson, a Salt Laker who brought it into prominence for commercial uses such as in paints and varnishes, and in other building products.

Gilsonite has been produced since the 1880s, and in 1886 claims were filed by Gilson, Burt Seaboldt, and others. Seaboldt experimented with the substance and observed that it was resistant to acids and moisture. He succeeded in having his mining claims removed from the Uintah Reservation. In 1888 the Gilsonite Manufacturing Company was organized in Salt Lake City. Reportedly, at that time some 3,000 tons of Gilsonite were shipped to Price and sold for $80.00 a ton. In 1889 the company sold out to the Gilson Asphaltum Company of Missouri, and by 1900 the Gilson Asphaltum Company of New Jersey had acquired the property.

As with metals and coal mining, efficient transportation proved necessary to the commercial development of Gilsonite. The Uintah Railway Company was begun in 1903 by the Barber Asphalt Paving Company. The Barber Company was owned by the General Asphalt Company, which was itself owned by the Gilson Asphaltum Company. In 1902 the Barber Company began the development of the Black Dragon vein, and in 1904 the Uintah Railway completed its fifty-three-mile narrow-gauge railroad to the mines. The line ran across the Book Cliffs from Dragon, Utah, to Mack, Colorado, where it connected with the Denver and Rio Grande Western main line. Wagon freighting costs in 1900 were reported to be from $10.00 to $15.00 per ton to carry the ore to the railhead, with rail costs at $10.00 per ton to Chicago or St. Louis. In 1911, the railway was extended to Watson, then four miles southwest to the Gilsonite mine at Rainbow. A wagon road called the Uintah Toll Road was built to carry freight and passengers over the sixty miles between Vernal, Fort Duchesne, and Dragon.

Ontario Mines The Shaft

Mining the vertical fissures of Gilsonite was difficult, as the veins were often quite narrow. Pick and shovel were the most useful mining tools. Ore would then be hoisted from the shafts. In the early days, veins were worked on a rising slope to permit the ore to roll back down the slope. When a sufficient amount had been loosened, the mineral would be loaded by hand into a burlap bag holding about 200 pounds. This method limited the depth of these operations to about 100 feet.

Uintah and Duchesne counties produced the principal Gilsonite mines—Dragon, Rainbow, Watson, Little Emma, Bonanza, and Little Bonanza were among them. In Duchesne County, the Parriette Mine (closed in 1900 because of an explosion) was located near Parriette Bench. In 1935 the main operation had been moved to Bonanza and ore was trucked to Craig, Colorado. This resulted in the eventual abandonment of the Uintah Railway.

Production figures illustrate the growth of the Gilsonite industry: 1904 (2,977 tons), 1905 (10,916 tons), 1929 (54,987 tons), and 1961 (470,000 tons). A new development plan in the 1950s by the American Gilsonite Company, successor to the Barber Asphalt Company, produced the increase in production to the 1961 level.

Other hydrocarbons found in eastern Utah which were sometimes mined on a small scale included kerogen (in the oil shales of the Green River formation), bituminous sandstone, wurlitzite (“elaterite” or mineral rubber), bituminous limestones, ozokerite (mineral wax), nigrite, and tabbyite.

The process of Utah’s settlement and growth necessitated a search for building materials including stone and limestone (used for mortar). Thus, quarries and lime kilns were found near many Utah cities and towns. Lime also became important commercially. The Utah Lime and Stone Company in Tooele County is recognized as among the oldest such commercial operations in Utah. Its plant at Dolomite prepared and sacked hydrated lime. Limestone was used in Utah’s sugar industry, where it was calcinated at the sugar refinery to obtain lime and carbon dioxide.

Red sandstone and white oolitic limestone (found in Sanpete County) were popular building materials. Fort Douglas in Salt Lake City utilized red sandstone found in nearby Red Butte Canyon. In Sanpete County, the quarries near the Manti LDS Temple attest to the use of the oolitic limestone in the temple itself. The Salt Lake LDS Temple and the Utah State Capitol Building were constructed of granite from Little Cottonwood Canyon.

Early quarries were generally developed by individuals and communities, with the stone quarried as it was needed. Stone was a popular building material in nineteenth-century Utah, especially after the initial settlement, when more permanent materials became desirable. Most of the masons involved in stonework were European: Danes and Swedes who had settled in Manti and Spring City, English in Heber City and Midway; and Italians and Greeks in Carbon County. Spring City in Sanpete County was built almost exclusively of stone—the light, cream-colored oolitic limestone quarried in the hills west of town. As brick became more available, the use of stone declined.

See: Utah Historical Quarterly 31 (1963); Herbert F. Kretchman, The Story of Gilsonite (1957); Ruth Winder Robertson, This Is Alta (1972); Richard W. Sadler, “The Impact of Mining on Salt Lake City,” Utah Historical Quarterly 47 (1979); Gary L. Shumway, “Uranium Mining on the Colorado Plateau,” in Allan Kent Powell, ed., San Juan County, Utah: People, Resources, and History (1983); George A. Thompson and Fraser Buck, Treasure Mountain Home, A Centennial History of Park City, Utah (1963).