Becky Bartholomew

History Blazer, December 1995

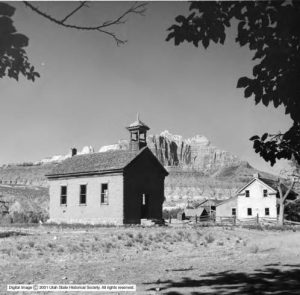

Grafton, Utah

What distinguished (or at least used to) a Mormon village from other western towns? According to Richard Francaviglia in his book The Mormon Landscape, a primary element was domestic architecture—house design. In contrast to the smaller, hip-roofed, frame houses that dominated the rest of the West, large and sturdy brick houses were the traditional architecture of Mormon towns. The brick might be fired or adobe, red or yellow, but the floor plan was almost uniformly symmetric, of the central-hall type called the Nauvoo style. They were Old Worldly in feel and usually boasted a gabled room with chimney at either end. Many also sported two front doors–seen by some observers as a sign of polygamists, although Francaviglia states that double doors were common in the East during the mid-1800s.

Even smaller Mormon pioneer houses had this strong if simple English appearance because of neo-Grecian cornices making heavy roof lines. It was not until about 1900 that Victorian-style houses began to be built by wealthier families. These homes had more complex floor plans, hipped roofs, and ornate bay windows, cornices, and porches.

Another uniquely Mormon town feature is the strict north-south grid with the LDS chapel as the focal point, the unusually wide streets (as much as 88 feet), and city blocks divided into four lots of about an acre each with a house on each corner. While many lots were later subdivided and the wide road shoulders left unused, many rural Utah towns retain a wide open feel. Dominating this spaciousness is the LDS chapel. Pioneer chapels were often sited in the central public square, appropriate to their function as the secular and religious focus of the community. Those built since 1950 almost uniformly boast rambling wings and tall steeples but no crosses or other conventional religious symbols. Buildings of other denominations are seldom seen. In some towns a separate Relief Society hall or bishop’s storehouse remains from pioneer days.

Rural scene from “In and Around Salt Lake City.” A farmer, woman, and two children are standing on a country dirt road. Behind them are trees, mountains, and a fence. 1889

“One more unpainted, crooked element in an already cluttered landscape” is how Francaviglia describes Mormon fences. Because the one-acre city lots were mini-farms with many uses, much fencing was needed–fences often built out of a medley of whatever materials and woods were available, including cedar, juniper, and even wagon wheels.

A few decades ago piped and pressurized irrigation systems replaced pioneer irrigation systems. Now even the empty ditches are disappearing as culinary and sewer upgrades require excavation and fill. But the ditches were once omnipresent, flowing along every street and byway, with diversion gates that directed a main stream into private orchard, garden, or pasture. Guillotine-like headgates controlled the larger channels. All were once a source of endless recreation for children. The ditches furnished the lifeblood to settlements entirely dependent on mountain snowpack for survival.

Poplar planting was so widespread in early Utah that the ubiquitous olive green trees still line irrigation ponds and canals. Along with steeples, the poplars direct the eye toward heaven, helping to form the basic horizontal/vertical composition of a Mormon landscape.

Francaviglia lists other elements of the Mormon townscape: the simple rectangular barn with pitched roof and adjoining shed on one or both sides; open hay barns, “usually the most dilapidated structure in the farmyard”–leaning at a slight angle or even propped up by hay; weathered granaries; inner-city corrals and woodpiles; the distinctive Mormon hay derrick; the protective barrier of mountains behind almost every Utah town.

Those weed-ridden road shoulders, unpainted barns, and rustic fences create a genteel shabbiness that sometimes inspires beautification committees to urge residents to mow their weeds and paint their houses and fences. Other Utahns—including many an artist—hope the villages will never change. But Utah’s rural landscape is changing, as new brick rectangles replace the adobe houses. In time it will be gone except for those buildings preserved by a few loving keepers.

Source: Richard V. Francaviglia, The Mormon Landscape: Existence, Creation, and Perception of a Unique Image in the American West (New York: AMS Press, 1978).