Curated in 1997 by Linda Thatcher

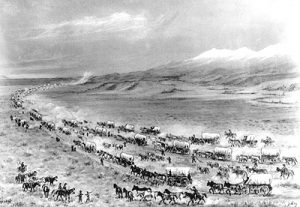

During the 1800s more than 500,000 emigrants crossed the Western plains hoping to find a new and better life for a variety of reasons. One of the largest groups to move west was the Mormons. From 1847 to 1868, 70,000 Mormon pioneers made the trek on foot, in wagon trains, or handcart companies to “Zion” (Salt Lake Valley) hoping to find a home where they could practice their religious beliefs without persecution. Those traveling to “Zion” came from a variety of backgrounds starting with the Saints that had been driven out of Nauvoo, to church members converted to Mormonism in England, Wales and Denmark.

In 1997 Utah and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints celebrated the Sesquentennial of the Mormon migration to honor the thousands of pioneers who made the trek to Utah. This photo exhibit was produced for the Sesquicentennial for schools and other interested groups to exhibit. The exhibit is presented here for those interested in the Mormon Trail to view.

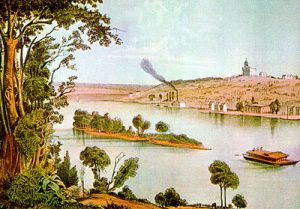

Nauvoo, Illinois. Color print by A. Henry Lewis.

By 1845 the Mormon population in and around Nauvoo, had grown to more than 11,000, making it one of the largest cities in Illinois. In September 1845 more than 200 Mormon homes and farm buildings were burned in an attempt to force the Mormons to leave the area. A move to the Far West had been discussed by LDS Church leaders as early as 1842, with Oregon, California, and Texas considered as potential destinations. In 1844 Joseph Smith obtained John C. Fremont’s map and report, which described the Great Salt Lake and its surrounding fertile valleys. Subsequently, the Rocky Mountains and the Great Basin became the prime candidates for settlement.

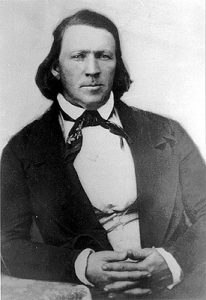

Brigham Young as he looked in about 1850

Under the leadership of Brigham Young the Mormons left Nauvoo earlier than planned because of the revocation of their city charter, growing rumors of U.S. government intervention, and fears that federal troops would march on the city. They left Nauvoo on February 4, 1846.

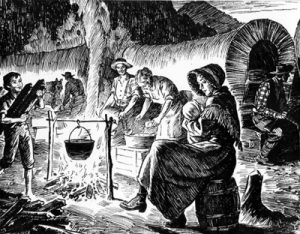

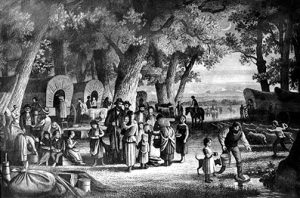

A Mormon camp in Iowa along the route to Winter Quarters after expulsion from Nauvoo in 1846.

After crossing the Mississippi River, the Mormons followed primitive territorial roads and Indian trails across Iowa. Their early departure exposed the pioneers to the worst winter elements. Heavy rains turned the rolling plains of southern Iowa into axle-deep mud. Furthermore, few pioneers carried adequate provisions for the trip. The weather, general unpreparedness, and lack of experience in moving such a large group of people, all contributed to the difficulties they endured. The Mormon migration came to be known for its preparedness, orderliness, discipline, safety, and effective organization, but that was later. The diaries written in those cold wagons during February and March yield a picture of confusion, disorder, and severe hardship. On March 27, 1846, Brigham Young issued instructions to organize the group into companies of 100s, 50s, and 10s.

A scene along the Mormon trail

The historic Mormon Trail developed in two stages: (1) from Sugar Creek across Iowa to Council Bluffs in the winter and spring of 1846, and (2) from Winter Quarters near Council Bluffs to the Rocky Mountains in the summer of 1847.

Camp at the end of the day

Brigham Young continued to exert his authority over the pioneers. On April 18, 1846, he laid out the daily routine of the camp: At five o’clock in the morning the bugle is to be sounded as a signal for every man to arise and attend prayers before he leaves his wagon. Then the people will engage in cooking, eating, feeding teams, etc., until seven o’clock, at which time the train is to move at the sound of the bugle. Each teamster is to keep beside his team with loaded gun in hand or within easy reach, while the extra men, observing the same rule regarding their weapons, are to walk by the side of the particular wagons to which they belong; and no man may leave his post without the permission of his officers. In case of an attack or any hostile demonstration by Indians, the wagons will travel in double file—the order of encampment to be in a circle. At half past eight each evening the bugles are to be sounded again, upon which signal all will hold prayers in their wagons, and be retired to rest by nine o’clock. Other rules included a noon rest for the animals. (The travelers were to have their dinner precooked to avoid the necessity of cooking at noon.) At night the wagons were drawn into a circle, and the animals grazed inside it where possible. When stock had to be staked out at night for feed, extra guards were posted.

All persons were to start together and keep together. A guard at the rear saw that nothing was left behind. Of course, even with strict discipline the realization of this ideal fell short at times.

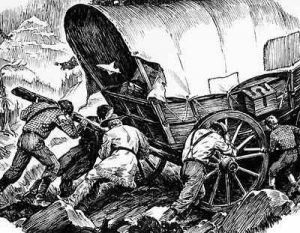

The trail over a steep mountain

Notwithstanding the better organization, it would be difficult to exaggerate the hardships of those first weeks on the trail. Sunrise temperatures were almost invariably below freezing until after April 15, 1846. Daytime temperatures rose enough to thaw the ground, and the heavily laden wagons became half-sunk in quagmires. Snowstorms continued through March. Rainstorms, sometimes lasting for days, pelted the wagon-dwellers much of April and May. Near Richardson’s Point, Iowa there was “one mud hole, six miles long.” Hosea Stout wrote on April 29, 1846, “This was an uncommonly wet rainy, muddy, miry disagreeable day. Very wet night last night the ground flooded in water[.]”

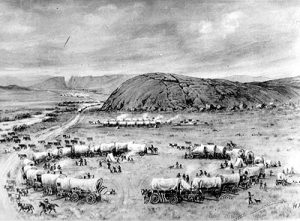

Crossing at Council Bluffs on the overland trail to the Far West. Frederick J. Piercy sketch

During the first stage of their journey in early June 1846 the camp moved on toward Council Bluffs, some 90 miles to the west, leaving behind enough people to improve and maintain Mount Pisgah for the benefit of future Saints going west. On June 13, the camp reached the Council Bluffs area at the Missouri River, and the first portion of the march was nearly over. In the Council Bluffs area the Mormons were not yet in the wilderness. In southern Iowa and eastern Nebraska between 1846 and 1853 the Mormons built at least fifty-five temporary and widely separated communities, farmed as much as 15,000 acres of land, and established three ferries. These numerous communities were established primarily to accommodate the thousands of Mormon emigrants, while they were waiting to cross either the Missouri River, or resting and preparing financially and physically to continue westward to Utah.

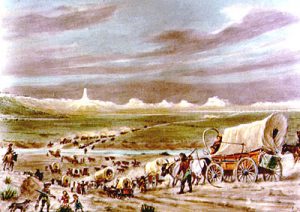

Covered wagon train scene in 1882

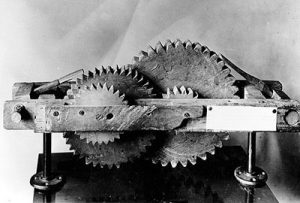

In early April 1847 the Mormon pioneers began the second stage of their trek west. Wagons began to trickle out of Winter Quarters in small groups. Near North Platte, Nebraska craftsmen devised a “roadometer” at the suggestion of William Clayton. Where it was first used is now known as the Odometer Start. Previously Clayton had kept track of distance by tying a red cloth to a wheel and counting the revolutions.

The roadometer was used by pioneers to measure the distance across the plains.

Camp along the trail

Life was hard on the trail. Women regularly began the trail day by getting up an hour or half an hour before the men to stoke the fire, heat the kettles of water to begin breakfast, milk the cow, etc. Cooking in the open was a new experience for most women. Two forked sticks were driven into the ground, a pole laid across, and the kettle swung upon it. Pots were continually falling into the fire, and families soon became accustomed to ashen crust on their food. After breakfast the women washed the tinware, stowed away the cooking equipment and food, and packed up while the men readied the wagons. After several hours on the road there was a brief stop at noon. Then the women brought out lunch usually prepared the night before. By evening everyone was ready to camp, where the work continued. The fire had to be kindled and water brought to camp. Men chopped wood, and children collected sagebrush, cottonwood twigs, or buffalo chips for the fire. Typical meals consisted of bacon, beans, cheese, boiled and mashed potatoes, dried fruit, homemade bread, biscuits, puddings. Some women even prepared preserves and jellies from wild berries and fruit gathered along the way. In the evening beds had to be made up, wagons cleaned out, and clothes mended or washed. Men fed and watered the livestock, mended harnesses, or repaired wagons in the evening; the work never ended for everyone on the trail.

Approaching Chimney Rock along the North Platte River in Nebraska. William Henry Jackson, 1929

One of the great landmarks on the emigrant trail was Chimney Rock in Nebraska, so named because its slender pillar rising above the bluffs resembled a giant chimney. The rock was shown on all early maps, and the Mormon pioneers were anxious to see it, both because of it fame and because it would give them a chance to check the accuracy of their maps. On May 22, 1847, Porter Rockwell rode into camp with some exciting news. He said he climbed atop a high bluff a mile distant and had seen Chimney Rock. But the emigrants did not reach the rock until May 26—where Orson Pratt estimated the height of the shaft at 260 feet.

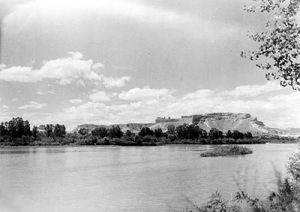

Scott’s Bluff from across the North Platte River

The trail across the Great Plains traversed hundreds of miles along the north side of the Platte and North Platte rivers. At Fort Laramie the Mormons crossed to the south side of the river, where they joined the Oregon Trail.

Fort Laramie, Wyoming, William Henry Jackson photograph

At Fort Laramie members of the Pioneer Company were halfway to their destination. From this point on, it was decided, they would follow the Oregon Trail. Terrain dictated the decision for the most part. They rented a flatboat for $15.00 and began ferrying their wagons across the river. They stayed at Fort Laramie for three days and obtained supplies at high prices—cotton and calico were a $1.00 per yard, flour was 254 a pound, a cow cost $15-$20 and a horse about $40. On June 4 started up the Oregon Trail, heading west and northwest, gaining in elevation over roads sometimes quite hilly. Making about 13 miles a day, their journey brought them on June 12 to where the Oregon Trail crossed the North Platte, 124 miles from Fort Laramie. Here (at present Casper) the Mormons remained six days, hunting and fishing and building rafts to ferry wagons. On the June 19 the pioneers’ company left the North Platte and rolled southwestward toward the Sweetwater River.

Independence Rock on the Mormon Trail by William Henry Jackson

On June 23 they reached Independence Rock, one of the most famous landmarks on the entire Mormon Trail. William Clayton wrote in his journal: “We can see a hugh pile of rocks to the southwest a few miles. We have supposed this to be the rock of Independent.” It is an oval-shaped outcrop of granite 1,900 feet long, 700 wide, and about 130 wide. Of the various stories regarding its name, the favorite is that some early trappers once celebrated the Fourth of July there. Mormons climbed it, danced on it, and painted and carved their names on it. The trail passed between the rock and the Sweetwater River in Wyoming.

Devil’s Gate, Sweet Water River, Rocky Mountains, 1869. Charles R. Savage, photographer

A few miles farther and the pioneers reached Devil’s Gate, another Oregon Trail landmark. The gate was a chasm 330 feet deep with the Sweetwater River running between the cliffs for about 200 yards. The pioneers camped a short distance beyond Devil’s Gate and many of them walked back to get a better view. Thomas Bullock called it “a romantic spot.”

South Pass, Wyoming, by William Henry Jackson

On June 26 the pioneers marched into the 25-mile-wide plain that is South Pass (which made the wagon trek west possible) near the Continental Divide-where waters west of the summit flow into the Pacific Ocean. The ascent on the broad plain is so gradual that many of the travelers crossed the Continental Divide without being aware of it since the Pass is 7,700 feet high, the pioneers sometimes enjoyed a snowball fight. On June 28 the company met Jim Bridger, on his way to Fort Laramie, who spent the night with them. Bridger gave a long account of the country around the Great Salt Lake. Bridger felt that one disadvantage to settling in the region was the cold nights. William Clayton reported: “He thinks Utah Lake is the best country in the vicinity of Salt Lake and the country is still better the farther south we go until reaching the desert about 200 miles south of Utah Lake.”

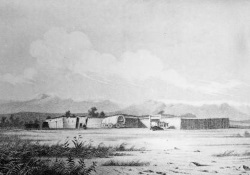

Fort Bridger, Wyoming, by William Henry Jackson

On July 7 the pioneers made it their goal to reach Fort Bridger-not because the trading post was important to them but because it marked the beginning of the last leg of their long trek. The structure was built in 1842 by Jim Bridger and opened as a trading post the next year by Bridger and his partner, Louis Vasquez. It was the second permanent settlement in Wyoming. The fort did business in the fur trade with trappers, mountain men, and Indians. As emigrants moved along the Oregon Trail, the post acquired many new customers. Having reached Fort Bridger the Mormon pioneers decided to “stay a day here and set some tires,” as well as rest their animals and do some shopping. Prices at Fort Bridger were higher than they had found at other trading places along the trail. Shirts cost $6.00, pants $6.00, and dressed animal skins $3.00 each.

Emigrant train in Echo Canyon on the way to Salt Lake City in 1867. The poles were used by the Transcontinental Telegraph, completed in the fall of 1861

On July 16 the pioneers reached “a narrow revine” Echo Canyon and attempts to travel along the bottom proved to be a struggle. Occasionally teams had to be doubled to get over obstacles. The company penetrated farther into the canyon. As they did, “the mountains seem to increase in height and come so near together as too barely leave room for a crooked road,” according to William Clayton. The wagons exited Echo Canyon and moved to near what is now Henefer. Ahead lay 36 miles of rugged mountains that taxed the strength of the pioneers and their teams.

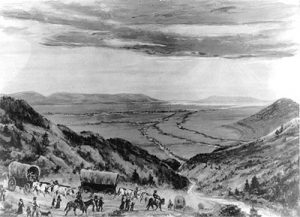

Painting by William Henry Jackson depicting the pioneers first view of the Salt Lake Valley in 1847

Orson Pratt’s advance guard was some distance in front of the main body, trying to improve the trail. Pratt and Erastus Snow were the first to enter the Salt Lake Valley on July 21, 1847, and a larger group followed on July 22, 1847. Thomas Bullock caught his first full view of the valley on July 22 and shouted “hurra, hurra, hurra, there’s my home at last.”

Hafen Brigham Young’s First View of the Valley. Artist John Hafen’s painting of the Mormon pioneers first view of the Salt Lake Valley

Brigham Young had fallen sick with “mountain fever” and was bringing up the rear with eight wagons. He was among the last to enter the valley, but his arrival July 24 made it official. Traveling six miles through Emigration Canyon “we came in full view of the great valley or basin,” according to Wilford Woodruff. “A land of promise, held in reserve by the hand of God for a resting place of the saints,” he thought, and declared this moment “an important day in the history of my life and the history of the church.” Young, still feeling weak, “expressed his full satisfaction in the appearance of the valley as a resting place for the saints and said he was amply repaid for the journey,” Woodruff later wrote. Nothing was mentioned in Woodruff’s journal at the time about Brigham’s having said, “This is the place.” Thirty-three years later, in recalling the 1847 event, Woodruff said that Young, looking over the expanse below, saw the future glory of the valley and said: “It is enough. This is the right place, drive on.”

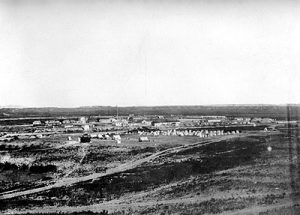

View of Salt Lake City in 1853, sketched by Frederick J. Piercy. This is one of the earliest views of Salt Lake City

At once the settlers began building their new empire. They diverted water from City Creek, planted crops, planned and laid out their city, and built homes. Brigham Young immediately set aside several acres for the Mormon Temple. Many early visitors were impressed with the layout of the city and commented on its clean, neat appearance. By 1850 there were 11,380 people living in Utah, and one visitor described Salt Lake in 1850 as “a large garden laid out in regular squares.” Mark Twain noted the clean streams that trickled through town. Mormons continued to arrive during the remaining weeks of summer and fall, and approximately 1,650 people spent that first winter in the valley. After organizing the settlement, Brigham Young and many members of the pioneer party made the return trip to Winter Quarters to be with their families and to help organize the next spring’s migration to the valley.