Nancy D. Taniguchi

Beehive History 16

Striking coal miners, April 1904, Price, Utah, were arrested and placed in this compound with armed guards. Labor leader Charles DeMolli is seated in foreground.

Utah’s coal industry has had a long and colorful past. Long, because of the early need for coal as a fuel; colorful, due to the people and events associated with it. Utah coal mining has had far-reaching effects on the state and the nation. Especially around the turn of the century, coal was truly king.

The earliest white settlers of Utah, members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, quickly demanded coal to heat homes and run businesses when the sparse local timber was reserved for building. In desperation the 1854 territorial legislature offered a cash prize for the first usable coal deposits found within forty miles of Salt Lake City. Unfortunately, the first coal discovered in Utah was much too far away to win the money.

During the 1850s, 1860s, and 1870s settlers discovered coal in other parts of the territory, including Utah’s southwestern corner and in centrally located Sanpete County. These mines began to fuel iron foundries, but the foundries soon closed. After that local farmers used the coal from what they called “wagon mines” or “country banks.”

Early Coal Discoveries

In the early 1860s coal was found at Coalville, Summit County, twenty-five miles from Salt Lake City. The Mormons built a connecting railroad to the Coalville deposit. This line was coveted by the Union Pacific Railroad (UP), then laying the first transcontinental line across the United States. A few years after the UP entered Utah Territory in 1869 it bought the Coalville railroad (and others) and almost monopolized Utah’s coal supply.

Utah’s leaders objected strongly to this unfair business practice. Understandably, they were overjoyed when the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad (D&RGW or Rio Grande) extended its route across Utah from 1881 to 1883. Now, residents thought, the UP would have some competition! The Rio Grande, however, soon proved just as monopolistic in the southeastern part of the state as the Union Pacific was in the north.

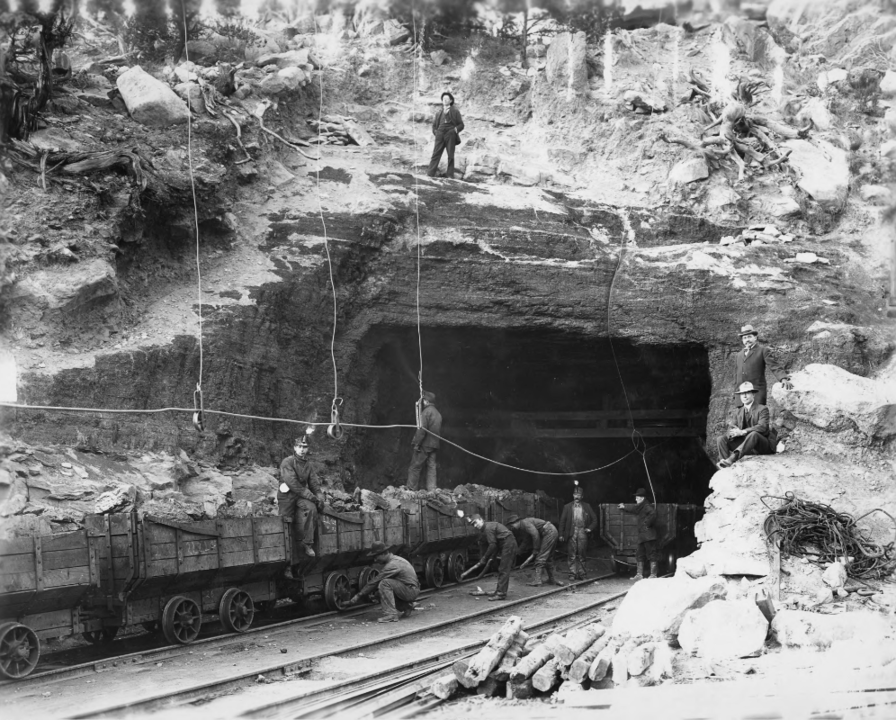

Coal mine in Cedar Canyon, Emery County.

The D&RGW was largely responsible for the development of Utah’s major coal belt, most of which lies in Carbon and Emery counties. In three quick steps the D&RGW surrounded most of this area’s commercial coal. First, in 1881 a Rio Grande geologist pinpointed a good deposit for locomotive fuel: the newly prospected Castle Gate Mine. Second, in 1882 the Rio Grande bought the Pleasant Valley Coal Company and Railroad, originally founded by a band of Sanpete Mormons in 1875. Third, the railroad got Sunnyside–the only Utah deposit of quality coking coal (used in smelting) in 1899.

To develop these mines the Rio Grande had to meet three major challenges. The first was labor. There were not enough settlers already in the area to man the mines. So the railroad hired labor agents to bring foreign immigrants to Utah to do this dangerous work. Lured by false promises of easy money, miners came from Italy, China, Finland, Greece, present-day Yugoslavia, Japan, and Mexico. Often brought in as strikebreakers, most of them remained and gave the area its distinctive ethnic mix.

Coal Miners’ Complaints

Company problems did not end with recruiting workers. The miners frequently complained about their working and living conditions. They complained about short weights (deliberate underweighing of coal), the basis for their pay. They did not like living in the company town and trading at the company store (where they had to pay high prices). They feared the dangerous working conditions that caused frequent injury and death. Most of all, they wanted a union to protect their rights.

Unidentified group of coal miners. In 1910 Utah coal mines employed 245 males between the ages of 10 and 20, 19 of whom were under age 16.

Many miners joined unions, mainly the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA). Because conditions were so bad–and company promises had been so rosy–union members sometimes went out on strike. The Winter Quarters miners were the first to walk out in 1883, a year after the D&RGW took control. In 1899 Sunnyside miners struck because their wages were dramatically lowered when development work ended and commercial mining began.

Miners’ concerns about dangerous working conditions led to other strikes. Their fears were justified when terrific explosions shook the Utah coal fields. The first such disaster, at Winter Quarters in 1900, killed 200 men and boys. A year later dangerous conditions remained, and miners struck without achieving any significant changes. In 1903–4 another strike was organized to try to gain the protection of a national union, the UMWA. It, too, was unsuccessful. A local

Rescue workers carry the body of one of the 200 miners killed in the Winter Quarters Mine explosion May 1, 1900.

strike shook Kenilworth, the first independent mine, in 1910. Utah’s coal miners joined another national strike in 1922, still fighting for recognition of their union. Utah strikers, driven out of company towns, set up tent cities outside company land. The mine owners mounted machine guns and searchlights on the mountainsides above the tent camps to keep an eye on the strikers. At least one of these machine-gun nests can still be seen today on the hill overlooking the Sunnyside tipple.

Coal mining at Independent Coal Co., Kenilworth, UT, Dec. 1, 1907.

The miners still lacked recognized union protection when an explosion rocked the Castle Gate Mine in 1924, killing 171. Ironically, Castle Gate was the first Utah mine to fire shots (explosives) electronically to blow coal off the walls so miners could load it into cars. The explosives were set off when all the miners were outside the mine. Even this safety measure had not prevented a disaster, so the miners kept demanding a union to improve their working conditions.

Union Recognition

Coal companies finally admitted organizers of the UMWA in 1933 after Congress passed the Wagner Act enforcing labor’s right to unionize. As miners escaped from company control, company towns shrank in size. Today, Hiawatha in southwestern Carbon County is the only full-fledged coal company town in Utah.

Coal loader, Carbon County

The Rio Grande’s domination of the early Utah coal industry was also challenged by federal investigators. Until the passage of the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920 United States law allowed people to buy coal land up to a maximum of 640 acres. The Rio Grande, like all other early coal developers, needed much more land (2,000–3,000 acres) for an efficient commercial mine. As a result, many early entrepreneurs got the land they needed by fraud. Agents of the federal government found out about this around 1905. Attorneys from the Justice Department prepared what they hoped would be the national “landmark” case for coal land fraud based on what they found in Utah. Prosecutions lasted from 1906 until 1932 when the last Utah coal land case was heard by the Supreme Court.

Coal cutting machine in one of the Carbon County mines.

The government was not as successful as it had hoped. The D&RGW hung on to its most profitable coal mines, as did independent developers who had also been brought to court. The case against one of these, Arthur A. Sweet, set a precedent in the U.S. Supreme Court that still stands. As a result of the Sweet case, states cannot claim coal land from the federal government at statehood. However, even federal court cases did little to break up already-established, large, commercial mines. Several huge, privately owned coal properties still exist as the legacy of this era.

Independent Operators

The third challenge faced by the turn-of the-century Rio Grande came from the new mines opened by independent developers. At first the D&RGW tried to squeeze them out by denying them railroad cars. Coal had to be moved in bulk, and before large trucks were introduced during World War II coal had to be carried on trains. Just when it looked like the D&RGW might be successful in monopolizing Utah’s richest coal belt, Congress passed the Hepburn Act of 1906. This law forced the railroad to treat its competitors more fairly. As a result, many new mines opened. The first, Kenilworth, began shipping coal over the Rio Grande tracks in 1906. Mormon businessman “Uncle” Jesse Knight began work in 1912 in the Spring Canyon District where several other developers followed in the period up through World War I.

UTAH BITUMINOUS COAL PRODUCTION — Selected Years

| Total | Tons | Value | |

| 1890 | 318,159 | $552,390 | |

| 1900 | 1,147,027 | $1,447,750 | |

| 1910 | 2,517,809 | $4,224,556 | |

| 1920 | 6,005,199 | $19,350,000 | |

| 1930 | 4,257,541 | $10,515,000 | |

| 1940 | 6,669,896 | $32,050,000 | |

| 1950 | 4,954,693 | $31,458,000 | |

| 1975 | 6,961,000 | $137,650,000 | |

| 1980 | 13,263,000 | $339,930,690 | |

| 1982 | 17,029,000 | $500,993,180 | |

| 1987 | 16,508,000 | $424,255,600 |

Average number of workers: 1920, 4,505; 1987, 2,544.

After World War I ended in 1918 all the coal mines—railroad and independent—faced the same problems, including that of labor (already described). A nationwide mining depression began in the 1920s. A few new mines, such as Columbia and Consumers, opened during this decade despite slow sales. The twenties depression in the coal industry deepened, however, as railroads switched to diesel fuel and homeowners to natural gas. Fewer mines opened in the thirties during the worldwide Great Depression. This downturn ended only when World War II pushed demands for Utah coal through the ceiling. Henry Kaiser then opened his mine near Sunnyside to help the war effort, and Horse Canyon opened a few miles east.

Coal mining, February 6, 1950, courtesy of the Salt Lake Tribune

Utah coal suffered again in the 1950s and 1960s. Then the combination of the original Clean Air Act of 1971 and the 1973–74 Arab oil embargo increased the demand for low-sulphur Utah coal. During the 1970s and 1980s energy companies bought several Utah coal mines. They use coal to generate electricity. Utah coal production reached an all-time high in the early 1980s, but it has sagged since then.

Partly to improve production, companies are using more and more machines to mine coal. Such equipment was originally blamed for the terrible Wilberg Mine Disaster of 1984, which killed 27 miners (including one woman). However, in 1990 a jury found the machine manufacturers free of blame and instead blamed mine operators.

Utah coal mining has brought a large, diverse number of people and a great deal of money to the state for more than a century. The industry still contributes to Utah’s wealth, although there are fewer jobs for miners than there used to be. It is still dangerous work but is gradually growing safer.

Endnotes

Dr. Taniguchi is assistant professor of history at California State University, Stanislaus. Philip F. Notarianni, “Copper, the King of the Oquirrh Mountains,” p. 18.