W. Paul Reeve

History Blazer, March 1995

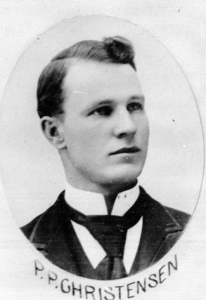

Parley Christensen

The short-lived farmer-labor party met in a poorly ventilated convention hall over a four-day period in mid-July 1920 to hammer out a political platform and to choose a candidate for president of the United States. By the end of the convention, delegates had adopted a platform that called for radical governmental reforms and nominated Parley P. Christensen, a Salt Lake City lawyer, as their presidential hopeful. Christensen, an unlikely candidate from politically unimportant Utah, traveled to Chicago to serve as joint chairman of the convention and returned home as Utah’s first ever presidential candidate.

Christensen was born in Weston, Idaho, on July 19, 1869. About a year later his family moved to Utah where he received his early education before attending Cornell University. He was awarded his law degree in 1897 and in September of the same year passed the Utah Bar and began a law practice in Salt Lake City. Prior to his presidential nomination Christensen had served in a variety of public positions, including principal of the Grantsville city schools, city attorney of Grantsville, Tooele County school superintendent, secretary of the Utah Constitutional Convention in 1895, Salt Lake County attorney, and representative in the Utah Legislature. He had previously worked in the Republican, Democratic, and Bull-Moose political camps before joining the Farmer-Labor party.

Represented at the Chicago convention were at least nineteen diverse groups seeking to unite into a new political movement. Due to the wide spectrum of ideas held by the delegates tempers often flared, and the convention frequently erupted with rowdy and colorful demonstrations. Even choosing a name for the new party proved challenging and when the platform was finally adopted several factions bolted, claiming their views were not adequately represented. In his position as chairman, Christensen’s commanding personality often emerged from the chaos to establish order and help resolve conflict.

After four tedious days of political wrangling, balloting for the party’s presidential candidate began. By far the most popular name among the delegates was that of Robert M. La Follette, the progressive, reform-minded senator from Wisconsin. Senator La Follette, however, found the Farmer-Labor platform too extreme to suit even his advanced notions of reform; he declined nomination, leaving the field open for lesser-known candidates. On the first ballot Dudley Field Malone, a lawyer from New York, and Christensen, the Utahn, emerged as the top contenders. One more ballot was all that Christensen needed to solidify his support and secure his party’s nomination.

In his brief acceptance speech Christensen affirmed his devotion to the party platform saying: “Every fiber in my system sounds in harmony with [it] and I can stand on it firmly and without equivocation.” The platform to which he readily espoused himself was built upon nine planks that critics claimed smacked of communism. Among other things, it called for equal suffrage for all, democratic control of industries, public ownership of all public utilities and natural resources, the right of all workers to strike, a maximum standard eight-hour work day, and the withdrawal of the United States from “the dictatorship” it exercised over the Philippines, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and Hawaii. Christensen promised if elected he would “go to the limit to see that every one of the planks is enacted into law.”

On July 23 Christensen returned to Utah and was met in Ogden by a committee of railroad shopmen who escorted him to a platform where he spoke to nearly 200 waiting railroad workers. He then traveled to Salt Lake where at eight o’clock that evening supporters held a parade down Main Street in which the city’s various labor organizations participated. Upon arriving at the City and County Building, Christensen delivered a speech declaring the Farmer-Labor platform a “one hundred percent American effort to restore to the people the right to govern themselves and to participate as freemen in the management of their economic and political affairs. . . . The first thing to be done after I am elected president,” he proclaimed, “will be to move the capital from Wall Street to Washington, where the constitution placed it.”

After spending a week in Salt Lake, Christensen left for New York where he began an extensive speaking campaign leading up to the election. When the votes were tallied Warren G. Harding had won a lopsided victory, and Christensen had finished a distant fourth behind James M. Cox, the Democrat, and Eugene V. Debs, the Socialist. Even in his home state Utah’s first presidential candidate failed to attract much support. He did manage to beat Debs by over a thousand votes in Utah but still finished third, garnering only a meager 3 percent of the vote.

Sources: Gaylon L. Caldwell, “Utah’s First Presidential Candidate,” Utah Historical Quarterly 28 (1960): 328–41; Salt Lake Tribune, July 15, 23, 1920; Deseret News, July 15, 23, 1920.