Julie Osborne

Beehive History 22

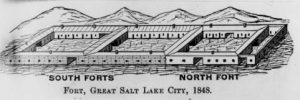

Pioneer Square. A sketch showing layout of Great Salt Lake Fort, or “the old Fort” consisting of the north and south forts. Digital Image © 2008 Utah State Historical Society.

After traveling many long weeks in wagons or pushing handcarts to their land of Zion, the Mormon pioneers first stopped at what became known as the Old Pioneer Fort–later Pioneer Park. There they met with others, rested, and learned of their ultimate destination before moving on to establish homes. Does this mean that Pioneer Park could be compared to Ellis Island? Perhaps it is not a national symbol, but it is important in the story of Mormon settlement. A Daughters of Utah Pioneers (DUP) pamphlet proclaims: “What Plymouth is to New England, the Old Fort is to the Great West.” The fort was a focal point of early Mormon activity, and the present park continues to reflect the city’s patterns of growth.

The building of the fort began a week after the arrival of the first immigrants in July 1847. Following the Mormon pattern for colonization that consisted of central planning and collective labor, the settlers formed groups to work for the common good. For example, one group began farming 35 acres. Another located the site for a temple and laid out a city of 135 ten-acre blocks. Each block was divided into eight lots (1.25 acres each). One block was selected for a fort or stockade of log cabins. The pioneers would live inside the fort until they could build permanent structures on their city lots. A large group began to build log cabins and an adobe wall around the fort. Within a month there were 29 log houses 8 to 9 feet high, 16 feet long, and 14 feet wide. In the fall of 1848 two additional ten-acre blocks were added to the fort. There were 450 log cabins, and the adobe wall around the fort was complete.

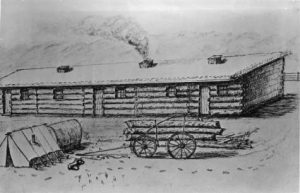

Pioneer Square. Sketch of typical dwelling at the “Old Fort” built by Brigham Young. The fort was completed in December of 1847. Used in Founding of Utah, Levi Edgar Young. Nicholas G. Morgan, donor. Digital Image © 2008 Utah State Historical Society.

Clara Decker Young, one of the first to move into the fort, was one of three women with the first group of pioneers. She felt relieved and satisfied when they reached their destination. The valley did not look so dreary to her as to the other women who felt desolate and lonely in the emptiness of the Great Basin with its lack of trees. Clara recalled the building of the houses within the fort and described “some crude contrivance for sawing lumber”–most likely a pit saw, commonly used to saw logs before sawmills were built. (It is a two-man operation using a large whipsaw with one man down in the pit and the other on top.) They made puncheon floors for the fort cabins of logs split in the middle and placed with the rounded sides down. Fireplaces for cooking and heating had chimneys of adobe brick (made in the adobe yard near the fort) and clay hearths.

The first homes were built along the east side of the fort for church leaders. The pioneers assumed that they had settled in a dry climate and used clay for plaster and piled dirt atop log and bark roofs. When the spring rains of 1848 came they caused considerable problems. The clay plaster could not stand exposure to rain and quickly melted. Historical accounts speak of the need to protect women and children indoors from the rain and mud with umbrellas while they were cooking and/or sleeping. Bread and other foods were gathered into the center of the rooms and protected with buffalo skins. Another serious problem plagued the fort dwellers–mice. One account says that frequently 50 or 60 had to be caught at night before the family could sleep.

Much of the furniture inside the homes was hand-made in Utah. Pioneer wagons carried few items of furniture. Bedsteads were built in a corner with the cabin walls forming two of the sides. Rails or poles formed the other two sides. Pegs were driven into the walls and the rails, and then heavy cord was wound tightly between the pegs to create a webbing on which to lay the mattress. Furniture often served several purposes. For example, a chest could be used as a table.

Community activities, including meetings of all kinds and even dances, were held in the fort’s log cabins. The home of Heber C. Kimball, consisting of five rooms built on the east side of the fort in August 1847, was the site of most civic and legislative meetings. On December 9, 1848, some 50 leaders met there to consider petitioning Congress for a state or territorial government. The first elections were held in an adobe school constructed inside the fort. Public meetings were often held near the liberty pole in the center of the fort.

Seventeen-year-old Mary Jane Dilworth held the first school classes in October 1847 in a small tent outside the fort. In January 1848 Julian Moses began teaching school in his log house inside the fort. In November 1848 a school was completed just east of the northwest corner of the fort. In a letter to the Deseret News dated August 10, 1888, Oliver B. Huntington, who taught school from November 1848 through February 1849, told about the school and the fort. The houses were built as part of the fort wall with portholes for defense on the outside walls. Usually, a cabin had a six-light (pane) window opening to the inside of the fort. The roofs were made of poles or split logs laid close together and covered with bark. “Such was the general makeup of ‘the first schoolroom,’ with an immense quantity of dirt piled on the flat roof as probable protection from the rain,” Huntington wrote. The 30-by-40-foot room where he taught had a hardened clay floor. The window opening was large enough for six panes of 8-by-10-inch glass, but glass and milled lumber for a sash were not available, and so thin cotton cloth that had been oiled was tacked to the primitive window frame. Writing tables, seats, and benches consisted of pieces of a wagon box laid on trestles, and a stove heated the school. The books on hand were inadequate for preparing pioneer children for life in the wilds, but education was still an important part of the early settlers’ lives.

The building of the fort and the laying out of Salt Lake City probably gave the pioneers a sense of security and inspired feelings of accomplishment. Although the fort no longer remains, the significance of the site and the beginning of Mormon settlement in the West has not been overlooked or forgotten. For two decades the fort was a center of city activity. Then the site became a campground for newly arrived immigrants. After 1890 it was used as a playground, and on July 24, 1898, the location was dedicated as Pioneer Park–one of 5 city parks. By 1900 there would be 9 parks in Utah’s capital city and a decade later 17.

The popularity of city parks was influenced by local and national trends. In 1906 women and men in Utah, like Progressives throughout the United States, embraced the ideals of the City Beautiful movement. They believed that the construction of parks and boulevards, combined with good urban planning, would improve the quality of life for city dwellers. In 1908 the Parks and Playgrounds Association was organized in an effort to improve existing playgrounds and open new facilities. In 1913 the Salt Lake City Commission created the Civic Planning and Art Commission to coordinate efforts to create a City Beautiful by proposing and implementing a 20-year plan to beautify Salt Lake City with boulevards, parks, playgrounds, street parking, and cleanup. In the 1920s a citywide beautification plan was adopted. These beautification efforts during the early 20th century were significant in the development of Salt Lake City. They also helped to keep Pioneer Park alive despite shifting population and land-use patterns during the 1920s-50s.

East side of the old fort in Pioneer Park Square. Digital Image © 2008 Utah State Historical Society.

During 1948-55 city officials explored other uses for Pioneer Park, such as turning it into a larger complex that would include a golf course or even selling it because of financial problems. Commissioner L. C. Romney tried to justify these options by noting that “recreational use of the park has dropped off in recent years, largely because the surrounding area is industrialized.” Still, many Utahns objected to any change in the park’s status. The Sons of Utah Pioneers and Daughters of Utah Pioneers were the most vocal in opposing those plans. Gaylen S. Young, a grandson of Brigham Young, also protested the sale of Pioneer Park, pointing out that the city, when soliciting the property from his father in 1889, had promised to preserve it as a public park. Others joined the chorus of those opposed to changing the park. Utah State Historical Society executive secretary A. R. Mortensen told the Salt Lake Tribune:

“Sure, it’s down by the tracks on the so-called wrong side of town, but so what? Here’s where it all began. The first settlement, the first houses, the first government, the first division of the city into its ecclesiastical wards, the reorganization of the First Presidency of the LDS Church, and a host of other firsts took place right here, not on the Temple Block, not on the old Eighth Ward Square, not on the old Union Square, but right here on the old Pioneer Square.”

City officials heard and accepted the outcry against selling the property or changing the park to a golf course, and Pioneer Park has remained to this day a city park.

In 1955 the Sons of Utah Pioneers Memorial Foundation created an elaborate plan for Pioneer Park, including a reproduction of the old Salt Lake Theatre, a model of the first schoolhouse, a museum, a log wall, and replicas of the original log cabins. Nothing came of this plan, but the idea of a replica of the fort surfaced again in 1971 as one of several projects under consideration by state officials. They wanted to replace the deteriorating areas west of downtown Salt Lake City with new residential areas, shopping centers, a concert hall, and museums. The Old Pioneer Fort Site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972.

In 1990 a Deseret News writer recounted the many attempts “to treat Pioneer Park as a monument to the founding of Utah and the settlement of the West,” but fear of violence, real or perceived, kept many away from the park. Its location near facilities such as the bus station, the Rescue Mission, the Salvation Army, and men’s and women’s shelters has made the park a natural congregating place for transients. Pioneer Park and its nearby amenities are known all over the country, drawing many vagrants to the city.

Plans for the revitalization of Pioneer Park and the west side of Salt Lake City’s downtown area seem to resurface about every 20 years. In the mid-1990s actual progress has been made to return portions of this industrialized area to residential use. Condominiums, apartments, and hotels have replaced weed-strewn vacant lots and deteriorating buildings. The city’s efforts to keep the park free from drugs and violence continue, and new activities such as the farmers’ market on summer weekends are attracting families to the area.

The place where people first came when arriving in Utah to find a new home was the area now called Pioneer Park. Something about this site continues to draw to it people who are seeking to find their way. Perhaps the efforts to regain the use of the park as a wholesome and safe place to congregate will reach fruition in the near future.