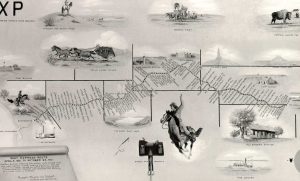

Pony Express Map

Jeffrey D. Nichols

History Blazer, January 1995

One of the most colorful, if brief, chapters in western history was the Pony Express, which carried the Overland Mail from St. Joseph, Missouri, to San Francisco, California, from April 1860 until October 1861. Utah Territory occupied a central position along the route, and many Utahns played a role as trailblazers, riders, agents, and station managers.

Mail service from East to West had presented a problem for decades, since the settled areas of the Midwest and California were separated by a vast stretch of sparse white settlement, sometimes hostile native inhabitants, treacherous weather, and inhospitable terrain. George Chorpenning and Absalom Woodward were awarded the first Overland Mail contract between Sacramento and Salt Lake City in 1851. Since their riders often delivered the mail by mule, wags dubbed this service the “jackass mail.” Plagued by Indian attacks (including the massacre of Woodward and his party) and financial troubles, Chorpenning had his contract annulled in 1860.

The Utah War of 1857-58 led indirectly to the establishment of the Pony Express. The freighting firm of Russell, Majors, & Waddell held the contract to supply three million pounds of material to Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston’s army. During the course of that strange conflict the company suffered major losses of equipment and livestock from Mormon militia attacks and harsh weather. William H. Russell failed to get the War Department to reimburse his firm for claimed losses of nearly half a million dollars. In order to save his company Russell proposed to launch a high-speed mail service across the “Central Route” between Missouri and California, expecting that the government would reward the firm with a lucrative subsidy.

Russell spent about $100,000 to launch the new service, which required hundreds of horses, riders, stations, station managers, and support services such as feed and blacksmithing. A. B. Miller, a company representative in Salt Lake City, advertised for 200 horses; some of those he obtained were mustangs captured near Kimball’s Junction and on Antelope Island. The greatest need, though, was for riders. The company called for young, light, brave, sober, God-fearing boys and men to carry the mail in grueling relays of 75 to 100 miles at a time at a full gallop across some of the West’s most brutal terrain. Many Utahns served as express riders, including Mormon pioneer and Nauvoo Legion major Howard Egan, who had helped blaze much of the original Central Overland Trail, and his sons Howard Ranson Egan and Richard Erastus Egan.

The riders and station managers endured many hardships, including a Paiute uprising that disrupted service for a month. Express rider Elijah “Nick” Wilson of Grantsville, Utah, was nearly killed by an arrow to the head near Spring Valley Station in Nevada. The Pony Express generally provided excellent service, covering the 1,966-mile one-way distance in ten days or less. It was always financially troubled, however; some of Russell’s shady dealings came to light, and he was forced to resign. The company, operating in the red as much as $1,000 a day, lost its contract to a competitor. The real threat, however, was technological. In October 1861 the Pacific Telegraph was completed at Salt Lake City, and messages could be relayed almost instantaneously. The Pony Express became obsolete overnight.