John S. McCormick

Utah History Encyclopedia, 1994

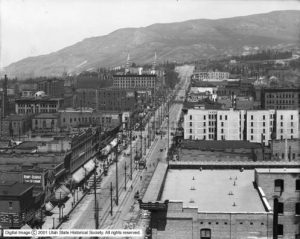

Main Street SLC looking north

The settlement of Salt Lake City was not typical in many ways of the westward movement of settlers and pioneers in the United States. The people who founded the city in 1847 were Mormons, members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. They did not come as individuals acting on their own, but as a well-organized, centrally directed group; and they came for a religious purpose, to establish a religious utopia in the wilderness, which they called the Kingdom of God on Earth. Like the Puritan founders of Massachusetts more than 200 years earlier, Mormons considered themselves on a mission from God, having been sent into the wilderness to establish a model society.

In many ways the history of Salt Lake is the story of that effort: its initial success; its movement away from the original ideas in the face of intense political, economic, and social pressure from the outside; and its increasing, but never complete, assimilation into the mainstream of American life. Its history has been the story of many peoples and of unsteady progress, and it was formed from a process of conflict—a conflict of ideas and values, of economic and political systems, of peoples with different cultural backgrounds, needs, and ambitions.

For about a generation after its founding, Salt Lake City was very much the kind of society its founders intended. A grand experiment in centralized planning and cooperative imagination, it was a relatively self-sufficient, egalitarian, and homogeneous society based mainly on irrigation agriculture and village industry. Religion infused almost every impulse, making it difficult to draw a line between religious and secular activities. A counterculture that differed in fundamental ways from its contemporary American society, it was close-knit, cohesive, and unified, a closely-woven fabric with only a few broken threads. The hand of the Mormon church was ever present and ever active.

The extent of early Mormon pioneer unity can be, and often is, overstated. Even so, for the first few years of settlement, it was Salt Lake’s most striking feature. Gradually at first, however, and then more rapidly, the city began to change. The completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 and the subsequent spread of a network of rails throughout the territory ended the area’s geographic isolation. Its economy became more diversified and integrated into the national picture. Mining and smelting became leading industries. A business district, for which there was no provision in the original city plan, began to emerge in Salt Lake City. A working-class ghetto took shape in the area near and west of the railroad tracks. Urban services developed in much the same time and manner as in other cities in the United States, and by the beginning of the twentieth century Salt Lake was for its time a modern city. Main Street was a maze of wires and poles; an electric streetcar system served 10,000 people a day. There were full-time police and fire departments, four daily newspapers, ten cigar factories, and a well-established red-light district in the central business district. The population became increasingly diverse. In 1870 more than 90 percent of Salt Lake’s 12,000 residents were Mormons. In the next twenty years the non-Mormon population grew two to three times as rapidly as did the Mormon population. By 1890 half of the city’s 45,000 residents were non-Mormons; and there was also increasing variety among them, as a portion of the flood of twenty million immigrants who came to the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries found its way to Utah.

As Salt Lake changed, and in particular as the population became increasingly diverse, conflict developed between Mormons and non-Mormons. During its second generation, that was the city’s most striking feature, just as earlier the degree of unity was most conspicuous; Salt Lake became a battleground between those who were part of the new and embraced it and those who were part of the old and sought to hold on to that. Local politics featured neither of the national political parties and few national issues. Instead, there were local parties—the Mormon church’s People’s party, and an anti-Mormon Liberal party—and during elections people essentially voted for or against the Mormon church. Separate Mormon and Gentile (non-Mormon) residential neighborhoods developed. While many Mormons engaged in agricultural pursuits, few Gentiles owned farms. Two school systems operated: a predominantly Mormon public one and a mainly non-Mormon private one. Fraternal and commercial organizations did not cross religious lines. Sometimes Mormons and non-Mormons even celebrated national holidays like the Fourth of July separately.

Conflict began to moderate after 1890 when, as a result of intense pressure from the federal government, particularly in the form of the Edmunds Act of 1882 and the Edmunds-Tucker Act of 1887, Mormon leaders decided to begin a process of accommodation to the larger society and endeavor to conform to national economic, political, and social norms. In 1890 Mormon church President Wilford Woodruff issued the Manifesto, which proclaimed an end to the further performance of plural marriages. A year later, the church dissolved its People’s party and divided the Mormon people between the Democratic and Republican parties. Following that, non-Mormons disbanded their Liberal party. During the next several years, the church abandoned its efforts to establish a self-sufficient, communitarian economy. It sold most church-owned businesses to private individuals and operated those it kept as income-producing ventures rather than as shared community enterprises.

These actions simply accelerated developments of the previous twenty years, and the next two or three decades were a watershed in Salt Lake’s history. The balance shifted during those years. By the 1920s, as Dale Morgan says, the city no longer offered the alternative to Babylon it once had, and the modern city had essentially emerged. The process has continued to the present, with Salt Lake City increasingly reflecting national patterns.

Since Utah became urbanized at about the same rate as the United States as a whole, Salt Lake faced the problems of urbanization and industrialization at the same time they were surfacing elsewhere, and it responded in similar ways. During the Progressive Era, for example, it established a regulated vice district on the west side, undertook a city beautification program, adopted the commission form of government in 1911, and that same year elected a socialist, Henry Lawrence, as city commissioner. The city languished through the 1920s, as the depressed conditions of mining and agriculture affected its prosperity. The Great Depression of the 1930s hit harder in Utah than it did in the nation as a whole. Salt Lake correspondingly suffered, making clear its close relationship with the world around it and its vulnerability to the fluctuations of the national economy; and New Deal programs were correspondingly important in both city and state.

World War II brought local prosperity as war industries proliferated along the Wasatch Front. In the post-war period defense industries remained important, and by the early 1960s Utah had the most defense-oriented economy in the nation. It has remained in the top ten ever since. During the 1950s a number of important capital improvement projects were undertaken, including a new airport terminal, improved parks and recreational facilities, upgraded storm sewers, and construction of the city’s first water-treatment plants. As a move to the suburbs began, the city’s population grew slowly, increasing by only 4 percent through the 1950s. Racial discrimination was still one of Salt Lake’s most serious problems. The real power in the city lay with a group of three men (though it is difficult to get specific information detailing their activities): David O. McKay, president of the Mormon church; Gus Backman, executive secretary of the Salt Lake City Chamber of Commerce; and John Fitzpatrick (and after his death in 1960, his successor, John H. Gallivan), publisher of the Salt Lake Tribune—representing, respectively, the city’s Mormon, inactive Mormon, and non-Mormon communities. The triumvirate continued to function through the 1960s.

Features of the period since 1960 include further enhancement of the city as the communications, financial, and industrial center of the Intermountain West; a declining population within the actual city boundaries (down fourteen percent between 1960 and 1980); the movement of both people and businesses to the suburbs as the valley population continues to increase; some decaying residential neighborhoods and a deteriorating downtown business district and the effort to deal with those conditions; the development of a post-industrial economy; and the rise to national prominence the Utah Jazz professional basketball team and of such cultural organizations as the Utah Symphony and Ballet West. The city’s population in 1990 was 159,936.

Yet through all of this, Salt Lake has never become a typical American city; it remains unique. The Mormon church is a dominant force, Mormonism is still its most conspicuous feature, and deep division between Mormons and non-Mormons continues, particularly on the social and cultural levels. There is still much to Nels Anderson’s observation in 1927 that Salt Lake is “a city of two selves,” a city with a “double personality.” As Dale Morgan observed more than forty years ago, Salt Lake is a “a strange town,” a place “with an obstinant character all its own.” That continues to be true.

See: Thomas G. Alexander and James B. Allen, Mormons and Gentiles: A History of Salt Lake City (1984); Robert Gottlieb and Peter Wiley, Empires in the Sun: The Rise of the New American West (1982); John S. McCormick, The Historic Buildings of Downtown Salt Lake City (1982); John S. McCormick, Salt Lake City, The Gathering Place: An Illustrated History (1980); and Dale L. Morgan, “Salt Lake City, City of the Saints,” in Ray B. West, ed., Rocky Mountain Cities (1949).