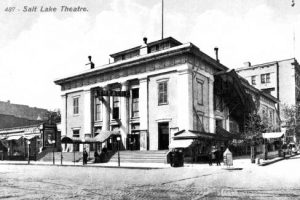

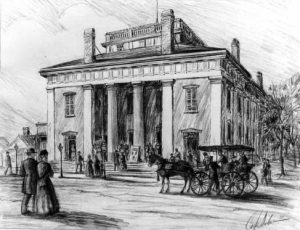

The Salt Lake Theatre was erected in 1861–62 at a cost of more than $100,000. William H. Folsom was the architect. The building was torn down in 1928

Ronald W. Walker

Utah History Encyclopedia, 1994

Public buildings often speak beyond themselves, suggesting the aspirations and activities of the people who occupied them, and few nineteenth-century Utah structures tell as important a story as the Salt Lake Theatre. Built in 1861 on the northwest corner of State Street and First South Street in Salt Lake City, it survived two-thirds of a century before it was razed in 1928. During this time, its activities charted early Utah cultural ideals as effectively as could a scholarly dissertation. There were manifold subplots as well. The Old Playhouse told of tension between Mormon and non-Mormon and of the assimilation of Eastern tastes and culture within the territory. Serving other functions, it also revealed the style of pioneer socials, and later of turn-of-the-century politics. Finally, efforts to save the Theatre disclosed the strain between historical preservation and modernity. In short, the Salt Lake Theatre embodied Utah’s early cultural, social, and political history.

From the beginning, the Salt Lake Theatre was a community expression, something like a medieval cathedral. Brigham Young himself announced the project and vigorously pursued its completion. At the time, Salt Lake City was a frontier outpost of 12,000 people. The telegraph had recently established rapid communication with the wider world, but no transcontinental railroad yet existed to freight supplies and facilitate construction of the building. Yet, before building an enlarged meeting hall for worship or completing the much delayed, religiously important Salt Lake Temple, the settlers erected the theatre, easily the largest and most imposing building in the community.

Part of the explanation lay with Young himself, who reportedly once

William West’s Minstrels. About March 10, 1901

declared if placed upon a cannibal island and charged with bringing civilization, he would construct a theatre. But part goes to the Mormons themselves. From Nauvoo days they had enjoyed drama, and on reaching Utah they staged productions at H. E. Bowring’s makeshift playhouse and at the Social Hall. Neither was adequate.

“To name all who took part in the building of the theatre would be an impossible task,” one historian, George D. Pyper, suggested, “for nearly every family residing in Great Salt Lake City at the time was represented.” Principals included Hiram B. Clawson, general supervisor; William H. Folsom, main architect; E. L.T. Harrison, interior designer; Alexander Gillespie, Henry Grow, Joseph Schofield, and Joseph A. Young, foremen; and George M. Ottinger, Henry Maiben, and William Morris, scenery painters.

Salt Lake Theatre

By modern standards the Salt Lake Theatre was not large. Its outer dimensions were 80 by 144 feet; its capacity was estimated at 1,500. In later years it was ill served by accumulated clutter: a distracting marquee, obstructing telephone lines, and an iron-grate stairway attached to its eastern wall. At first, however, its exterior lines were chaste. Two simple Doric columns commanded the entrance, which had an inviting space of thirty-two by twenty feet. The remainder of the facade was distinguished by simple lines and by the chalky white plaster that seemed magical at nightfall. In contrast, the interior, particularly after an 1873 renovation, strove for elegance. It was fashioned in the style of a European opera house with a commodious parquet and four ascending circles. Two boxes overlooked the sloping and unusually spacious stage. Farther to the rear, the theatre had ample dressing, rehearsal, and storage rooms that few American or European playhouses at the time could equal.

From the first, the Salt Lake Theatre aimed to provide “proper” drama in an uplifting atmosphere. When U. S. Army cavalrymen threatened decorum, their attendance was temporarily forbidden; if on-stage realism became too stark, it was suspended. Even too vociferous an audience might draw from Brigham Young a watchful look. Plays ranged from Shakespeare to more common didactic melodrama. At the beginning, “home” or stock companies, often supported by a professional actor or actress in a main role, formed productions. But the emphasis later shifted to touring stage companies, with little local participation.

There was scarcely a luminary of the American stage who did not make an appearance: Maude Adams; P. T. Barnum; Drew, Ethyl, John, and Lionel Barrymore; Sarah Bernhardt; Edwin Booth; Billie Burke; “Buffalo Bill” Cody; Fanny Davenport; John Drew; Eddie Foy, Charles and Daniel Froham; Al Jolson; Lillian Russell; Dewitt Talmage; and scores besides.

There were also miscellaneous events. George Francis Train, Oscar Wilde,

Salt Lake Theatre (exact date unknown; sometime after 1896)

and the phrenologist Dr. Orson Fowler lectured. Japanese musclemen and sleight-of-hand magicians performed. Symptomatic of Utah’s abandonment of the theocratic ideal of single-party government, in the 1900s the Salt Lake Theatre hosted Democratic and Republican caucuses and conventions, and in the process cradled the state’s modern political campaigning. There were socials, too. The dress circle curved in a perfect semicircle to allow the placing of a movable floor over the parquet seats. Once positioned, the flooring permitted everything from children’s parties to grand balls in the most extravagant style. Over the years there were formal balls in celebration of the Mormon Battalion, the Pioneers, and American Independence; state or military occasions for the territory’s officialdom; and benefit dances for city firemen, the Deseret Hospital, or Jewish charity. Fifteen hundred men and women might attend, with a many as 200 dancers on the floor at once.

The Salt Lake Theatre’s financial history was checkered at best. It was probably rescued from insolvency in the 1880s when a fire razed the rival Walker Opera House. But receipts never did much more than meet expenses. By the first decade of the twentieth century, things were bleak. Vaudeville, motion pictures, and the leisure-use automobile took customers from the seats. The situation was made still more difficult by plays staged by touring troupes. Mormon general authorities, who either formally or informally had controlled the theatre from the start, were increasingly offended by what they viewed as deteriorating dramatic standards.

As Utah’s economy struggled in the depressed 1920s, Mormon church president Heber J. Grant announced his intention to close the building. For Grant, who had attended productions from his youth and once had owned the building as a trust for the church, the decision was troubling but necessary. For other Utahns, however, the announcement was a violation of pioneer heritage. Throughout 1928 the controversy went on, with the Daughters of the Utah Pioneers especially active to trying to retain the building. Suggestions that the theater be refurbished, transformed into a museum, or moved to a less valuable location were each rejected. Neither local nor state authorities were willing to preserve it.

However, the building proved an obdurate foe to the wreckers. Its large, red-pine structural timbers were sound, and the building remained unusually tightly fitted. Such pioneer workmanship, combined with the structure’s bastion-like walls, meant that several more months of demolition than planned were required. At the time of its demise, the Salt Lake Theatre was nationally regarded as one of three or four great historic American stages.

See: George D. Pyper, The Romance of an Old Playhouse (1928); Horace G. Whitney, “The Story of the Salt Lake Theatre,” Improvement Era 18 (April–July 1915); Ronald W. Walker and Alexander M. Starr, “Shattering the Vase: The Razing of the Old Salt Lake Theatre,” Utah Historical Quarterly 57 (winter 1989).