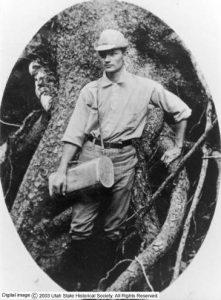

The first range ecologist, he was the father of range management.

The first range ecologist, he was the father of range management.

Arthur William Sampson’s list of “firsts” is impressive: first person in America to be called a range ecologist, first to promote deferred and rotational grazing strategies, first to develop usable concepts of indicator species and plant succession for evaluating range condition, first to write a college text on range management, first range ecologist hired by the Forest Service, and first director of what is now called the Intermountain Research Station.

Sampson’s initial goal as a range scientist was to develop practical range evaluation methods that everyday range managers could use. His indicator species concept helped to fulfill that goal. He described four stages of plant succession on ranges that indicated, roughly, excellent, good, fair, and poor range conditions. His specific studies of the reaction of lands to grazing led to range management techniques that combat range deterioration and promote restoration.

Basic principles of range management now taken for granted came from the early research of Sampson and James T. Jardine, the first director of the Forest Service’s Office of Grazing Studies, created in 1910. They include using the kind of livestock best adapted to the range, grazing proper numbers, grazing in proper season, and good distribution of livestock.

Sampson was born in Nebraska on March 27, 1884. He studied botany and plant ecology at the University of Nebraska, receiving a B.S. degree in 1906 and an M.A. degree in 1907. He then joined the Forest Service as a plant ecologist and began research on overgrazing in the Blue Mountains of Oregon. His observations were keen and led to the first of his more than 200 scientific publications just one year after he joined the Forest Service.

In 1912, at Jardine’s request, Sampson became the first director of the Utah Experiment Station, soon renamed the Great Basin Experiment Station. Located in the Manti National Forest near Ephraim, it was the beginning of what today is the Intermountain Research Station headquartered in Ogden.

Devastating spring floods, year-around erosion, and periodic mudflows that damaged or destroyed communities and ruined lands had plagued the West for decades. Sampson’s mission was to study the relationship between these disasters and overgrazing. He built several exclosures in Ephraim Canyon and adjacent drainages on the east side of the Wasatch Plateau. Log fences kept domestic livestock and most wildlife off these areas so that Sampson and two generations of scientists after him could study what happens to soil and plants when there is no grazing. From these exclosures scientists have access today to some 80 years of accumulated data.

Sampson’s studies covered three broad areas: production of maximum  forage through artificial and natural reseeding; utilization of forests by livestock without undue damage to plant reproduction and watershed conditions; and securing the greatest grazing efficiency per unit, including herding methods, water development, and poisonous plant studies.

forage through artificial and natural reseeding; utilization of forests by livestock without undue damage to plant reproduction and watershed conditions; and securing the greatest grazing efficiency per unit, including herding methods, water development, and poisonous plant studies.

Sammy, as he was called, was almost as avid a sportsman as he was a scientist. In college he trained as a wrestler and long-distance runner. As a graduate student he had the weekly job of hiking seven miles, including a 3,000-foot elevation gain, up a mountain to change the record sheet on temperature recording instruments, and he once broke a record for sprinting to the summit of Pikes Peak. In Utah he boxed under the name “The Utah Kid.” Later, he pitched horseshoes with his students at UC Berkeley.

Sampson headed the Great Basin Station until 1922. During those years he also completed a doctoral degree at George Washington University in 1917. In 1922 he left the Forest Service to teach at the University of California at Berkeley where he started the first range management courses and wrote four textbooks. Range and Pasture Management (1923) earned him the title “father of range management” because it was the first comprehensive text on that subject. During his long and distinguished scientific career Sampson received many awards from forestry, range, and ecological organizations. He retired in 1951 but continued his research. He died in 1967.