Miriam B. Murphy

History Blazer, October 1995

Drawing from Harpers’ Weekly showing telegraph operators on work

On May 24, 1844, the message “What hath God wrought” was sent by telegraph from Baltimore, Maryland, to the Capitol in Washington, D.C. A new era in long-distance communications had begun. Within a few years local companies were busily stringing the “talking wire” between many cities and towns.

In 1861 the Pacific Telegraph Company made plans to complete a telegraph line from Omaha, Nebraska, to California. The Overland Telegraph Company agreed to build the western portion of the line to Salt Lake City while Pacific built the line from Omaha to the Utah capital. The two companies completed their work in October 1861. President Abraham Lincoln, Brigham Young, and other officials sent the first messages over the new transcontinental line.

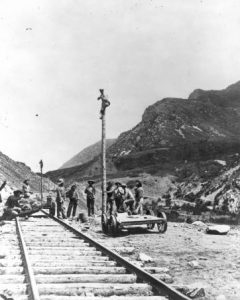

Building telegraph lines in Weber Canyon

Most of Utah’s early settlements lay north or south of Salt Lake City. Because the new telegraph line ran generally east to west across Utah, it did little to improve communications within the territory. So, Brigham Young and others decided to build the Deseret Telegraph to connect the outlying Utah towns with Salt Lake City. The difficulty of obtaining supplies during the Civil War delayed the building of the Deseret Telegraph until 1866. But before any wire was strung a call went out for young men from every town to come to Salt Lake City on December 15, 1865, to attend a telegraphy school. William A. C. Bryan of Nephi was one of those who signed up for the class taught by telegraph operator John C. Clowes.

Telegraphy fascinated William Bryan. Once he even climbed a telegraph pole hoping to “see” a message “fly” by on the wire. His curiosity unsatisfied, he followed the wires to the telegraph office in Salt Lake. Instead of flying messages the operators showed the boy batteries, keys, sounders, relays, switches, registers, and tape punched with Morse Code dots and dashes. No wonder he was eager to learn more.

As segments of the Deseret Telegraph line were completed, students from the telegraphy school took charge of operations in the various settlements. William Bryan ran the telegraph office in his hometown of Nephi–but not for long. Years later he remembered why so many young women learned telegraphy: “There was not much commercial business, and the line did not pay its way. All of the operators were men, and some of them had families to support….President Young called upon all of the men and boy operators to teach the art to young ladies, as he thought it probable that they could give more economical service, so we told the girls to put on their bonnets and come to see us.”

Four young women of Nephi took up the job with enthusiasm: Elizabeth Claridge, Belle Parks, Hetty Grace, and Mary Ellen Love. As Mary Ellen recalled: “We girls had a happy, busy time that summer and enjoyed our study and practice of telegraphy…in the fall we were assigned to take charge of different offices….we… [kept] in touch with each other by making use of the privilege of chatting over the line after business hours…. President Young’s policy was to place the girls in safer situations and send the boys out to the overland mail stations, mining camps, etc.”

Belle Parks, later the wife of William Bryan, took over the Nephi telegraph office. Elizabeth was sent to Mona, Hetty to Round Valley (present-day Holden), and Mary Ellen to Fountain Green.

Belle remained the telegraph operator at Nephi for a long time. Since some small-town telegraph “offices” were in homes, women like Belle could go about their usual housework in between answering the call of the telegraph. Some of them earned a little money for themselves or their families by providing this vital communications service.

Elizabeth, who was just 15 when she learned telegraphy, saved enough money from her small salary to buy a few clothes. She was a skilled operator with a great organizational ability. In 1870 Erastus Snow brought her from the Muddy River settlements in Nevada to take charge of the telegraph office in St. George.

William Bryan became a telegraph operator west of Salt Lake City on the Wells Fargo mail line. He also accompanied Brigham Young as his private operator when the pioneer leader made his tours of the distant settlements. Then, as now, knowing the news of the day was important, and the telegraph provided services now rendered by telephone, radio, and television. William remembered his trips with Brigham Young: “The President always wanted the news of the day,…every day;…and while on the road from place to place, his secretary in Salt Lake City would read and compile the news from the papers, and such local news as might be desirable for the President, and when I would cut in with my telegraph apparatus and give my signal to the Salt Lake office, my pen would begin sweeping over the paper like magic, copying the news….Often the President stopped at places where there was no telegraph office. At such places I would cut the wires and establish my office;…anywhere….” Anywhere was once on top of a wood pile at Scipio in a snowstorm!

Telegraphy may have lacked the daring challenges of the Pony Express and the glamour and big salaries of television, but to the young men and women of Utah who became telegraph operators it was an exciting new field—a scientific wonder as amazing in its way as a computer microchip or a communications satellite. Most important of all, the telegraph revolutionized communications. News that had sometimes taken months to reach Utah took only a few minutes on the telegraph. Business, politics, jobs, home, and family were all affected by the speed with which messages and news could be sent.

See: Miriam B. Murphy, “The Telegraph Comes to Utah,” Beehive History 8 (1982)