By Mark Karpinski, Elizabeth Karpinski, Jonathan Dugmore, Samantha Kirkley, and Garrett Webb

By the early 1900’s the United States coal industry housed between 70 and 80 percent of its workforce in company owned housing. Heiner, Utah was one of many coal company towns that emerged in Carbon and Emery counties as Utah rapidly industrialized and urbanized during the late 19th and early 20th century (Figure 1). Coal was critical to Utah’s development as the arid environment made wood supplies small, slow growing, and sparsely distributed. Fuel shortages had brought suffering to residents during the winter months and limited the region’s economic development. Early development attempts of local coal sources in Sanpete and Wasatch counties proved unsuccessful. By 1870, the Union Pacific (UP) was shipping coal to the Wasatch Front from its mines in southwestern Wyoming; however the railroad’s monopoly on coal supply and transportation caused discontent among Utah residents and industry. Reports from the northern and eastern side of the Wasatch Plateau described 23 feet thick coal seams with estimated reserves at 88 billion tons of bituminous coal exhibiting excellent coking qualities. The news prompted the Denver Rio Grande (DRG) to build west through the newly reported coal fields to Salt Lake City instead of south to El Paso, Texas. For Utah, the completion of the new railroad line in 1883 ignited a coal development boom brought on by the convergence of an abundant high quality local coal source and rail transportation able to haul the sufficient qualities needed along the Wasatch Front.

During the initial years of its development, the railroads controlled the majority of the Utah coal industry in Carbon and Emery countries. When Progressive-era trust busting broke the railroad’s monopoly on the coal industry, non-railroad corporate entities funded both locally and by eastern financiers rushed to open their own mines and towns. The company town of Heiner, Utah and its associated Panther Mine developed during out of this governmental opening of the Utah coal fields. Heiner, Utah was founded in 1909 when Frank M. Cameron and Sam C. Sherrell purchased two ranches totaling approximately 350 acres situated on the north side of Price Canyon. Their intention was to establish a coal mine focused on the Castle Gate B coal seam to serve the residential coal demands of Salt Lake City and western Utah. By April Cameron, Sherrell, and about 30 immigrant laborers had begun developing the mine and established the town site. The mine and town were named “Panther” after the adjacent canyon, but was renamed Carbon in 1913 due to the United States Post Office prohibition on naming towns after wild animals. By 1912, 20 miners are reported to have been producing four cars of coal per week and, that same year, Cameron sold the Panther Mine along with his other mines to W. G. Sharp’s Consolidated Fuel Company. In 1915 the recently incorporated United States Fuel Company (USFC), a subsidiary of the Salt Lake-based United States Smelting, Refining, and Mining Company, purchased the mine and town. The town at the time consisted of a two room school house and a series of boarding houses segregated by race. Compared to USFC’s Emery County mines of Hiawatha, Black Hawk, and Mohrland, Panther Mine was small in both annual tonnage produced and number of miners employed. A 1915 Utah State Mine Inspector Report lists Panther Mine as employing 30 miners to produce 44,571 short tons. The same report lists Hiawatha as employing 180 miners to produce 222,228 short tons; Black Hawk as employing 298 miner to produce 118,132 short tons; and Mohrland employing 284 miners to produce 264,510 short tons.

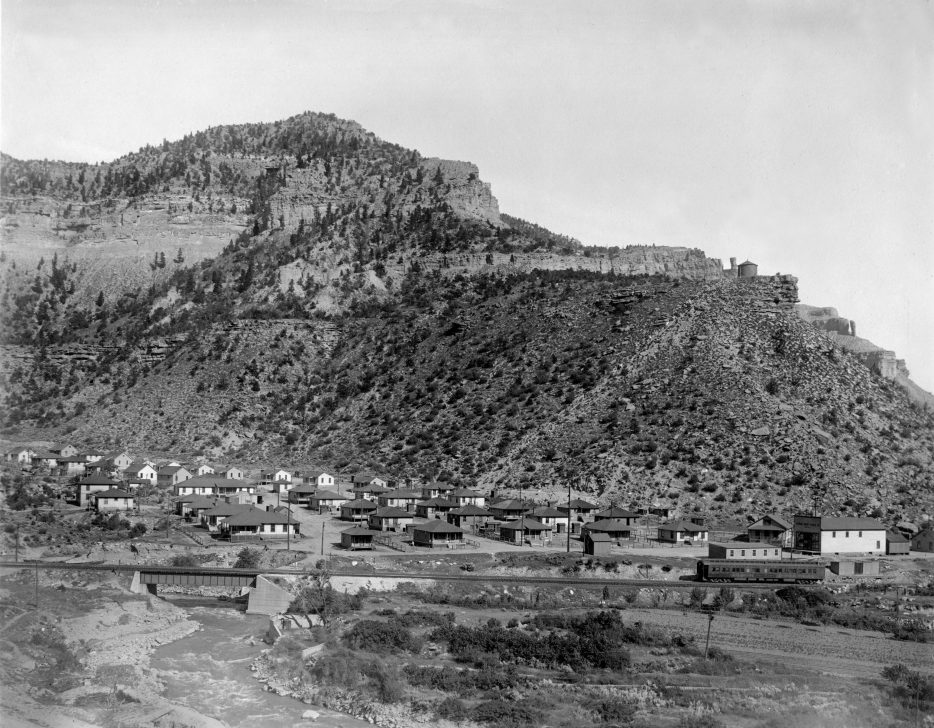

The town changed names to Heiner on October 18th 1918. It was named after Moroni Heiner, the vice president of USFC and longtime Utah-based mine developer and backer of progressive-era railroad trust busting. By 1919 the company was investing significantly into their company towns Heiner appears to have changed from a series of boarding houses to a planned community of single family homes (Figure 2). Heiner was laid out in a grid trending east to west up Panther Canyon. A four-room brick school house was built and the town got electricity, culinary water, a company store, and a post office. Heiner’s company store was the USFC’s subsidiary Carbon-Emery Stores Co., situated in the southwestern edge of town along the Denver-Rio Grande railroad. The Post Office was in the northwest edge of town also along the railroad. The change was partially fueled by the paternalistic business models of the day that attempted to provide goods and services to their work force in hopes of producing a more complaint and productive work force.

Heiner’s 1920 census lists 138 residents in the town. By 1930 the town’s population had increased to 316 individuals. Heiner had a large population non-working age children. The 1920 census records list 49 (34 percent of the total) residents were under the age of 16. The 1930 census had 133 (45 percent of the total population) of residents under the age of 16. The children represent the first generation of sub-16 year olds who were legally barred from mine work and who also had ready access to public education within their town. The two census reports show that the town’s population turned over 95 percent within covered 10 year period. Only three residents appear on both reports. At the time, miners tended to be a highly mobile workforce due to seasonal demands, individual mine conditions, and short-term regional and national market conditions. Pre-mechanized, underground room and pillar mining methods made for hard working conditions with constant safety issues. Inspection reports list Utah as having one of the highest injury/death to work hour’s ratios in the country during this period. Many miners only worked long enough to earn the money to establish themselves back in their home country and/or start businesses or purchase land in the U.S. Heiner’s turnover also can be due to blacklists developed in response to unionization efforts, especially from the region wide strike in 1922.

Immigrants arriving in the Utah coal fields during this period were part of what is referred to as the Third Wave. Third Wave immigrants were predominately from southeastern Europe, the Mediterranean, and Asia fleeing regional overpopulation; economic underdevelopment; little to no access to usable land; repressive government; and/or ethnic discrimination. Hiring agencies working in targeted nations, stationed outside major ports of entry, and/or in cities like Salt Lake City to recruit laborers for the coal fields. The hiring agencies varied from independent recruiters “selling” job opportunities to Padrones within immigrant communities that controlled access to wage labor in exchange for a percentage of the immigrant’s wages. Utah Padrones involved in staffing the coal industry included the Greek immigrant Leonidas G. Skliris (aka ‘Czar of the Greeks’) and the Japanese immigrant Daigoro Hashimoto whose store anchored Salt Lake City’s Japanese neighborhood. Heiner’s ethnic makeup included Euro-Americans, Italians, Greek, Austrian, Jugoslav, Japanese, and Czechoslovakian immigrants.

Heiner’s demographic makeup reflected Third Wave immigration; however coal company hiring practices intentionally managed the demographic makeup of their towns. Heiner’s foreign born population never exceeded 20 percent of the total population. Coal companies saw a diverse workforce as a divided work force that helped inhibit worker collective action and unionization efforts. Eighty percent of Heiner residents were U.S. born citizens with most of residents being from Utah. The town’s immigrant population was incredibly diverse for its size with 11 different countries of origin reported and six different languages spoken in the town in the 1930 census. In 1915 Heiner’s boarding houses were segregated by ethnicity; however no evidence of ethnic neighborhoods or subdivisions existed in the town after the company transitioned it into a planned community in the 1920’s. The three farmers listed as boarders in the 1920 census conducted on January 14 and 15 are reported as local Utahans. They likely represent regional farmers taking winter mining jobs to supplement income when the mines were busy and the farmers were not.

Daily life in Heiner was more reflective of the urban working class at the time than the surrounding rural agrarian and ranching communities of Utah. Companies built their towns so the miners could focus on mining and the families did not need practice self-sufficiency to the extent pioneers and homesteaders needed to even by the early 20th century. Most goods and services were purchased from the company store, traveling grocers, and in Helper or Price. Medical services were available in town, garbage services were provided, and education for non-working aged children was available. The rented company homes had electricity and culinary water. Rents ranged from $6 to $25 per month with most rents being either $8 or $11 per month. A 1928 article in the Salt Lake Mining Review by U.S. Smelting, Refining and Mining Vice President and General Manager Downie D. Muir Jr. states the company encouraged residential investment and community pride with yearly garden contests. Heiner resident Martin Perrero’s won best vegetable garden in 1929 (Figure 3). However, most residents did not garden for food and grew lawns and aesthetic landscaping. By 1930 Heiner had 47 miners in residence with additional workers of tipple men, unskilled laborers, a driver, carpenters, school staff, policemen, shoemaker, and a boilerman helper. Heiner was never organized as a municipal entity. Services and law enforcement was handled by company offices and the county sheriff’s office.

A 1929 company pamphlet by Otto Herres claimed their towns were “known in mining circles of the country for their excellence.” A government report on coal miner welfare to the American Institute of Mining Engineers included a description of the USFC mining town of Hiawatha. The town was reported a well planned community of high construction quality with a modern hospital, two churches, a bowling alley, pool hall, and a movie theater. The profits from the amusement facilities were re-invested in the community. The USFC even built and operated a modern dairy to supply milk, butter, and ice cream to the company towns of Hiawatha, Mohrland, and West Hiawatha. Heiner had no similar amusement establishments, hospital, churches, or facilities compared to the other USFC company towns. Heiner’s comparative small size and close proximity to Helper, Utah likely rendered the need for the company to invest in such facilities as unnecessary. Heiner did have a doctor’s office that was staffed by a nurse every day with frequent visits from the company doctor.

The coal industry would slowly decline throughout the 1920’s and the Great Depression brought the end of company towns like Heiner. In the early 1930s the USFC leased Panther mine to Frank Hennes, who continued mining operations with an eight man work force until the mine was closed in April 17, 1937. A 1933 letter from town resident Hugh McMillian to Utah Governor Henry H. Blood described the town as in poor condition with 15 empty and dilapidated houses. The letter’s author and five other families had been served with eviction notices by the company due to their inability to pay rent. By 1935 a Carbon County school census lists Heiner’s student enrollment at 69 pupils, down by half from 1930. The reasons for final closure of Heiner and the Panther Mine range from the coal seam becoming exhausted, coal quality dropping significantly, and/or market conditions making the mine uneconomical. In 1938, Heiner was abandoned by the USFC and the buildings were either dismantled or sold off. The four room school was sold and moved to Helper, Utah where it served as a Ward House for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints until its demolition and replacement in 1984. However, the end of company town’s like Heiner did not end Utah’s coal industry. The industry emerged in mid-20th century fundamentally different as automation significantly dropped the labor demand and the coal market shifted from residential/industrial applications to electrical generation in the power plants being constructed across the region. However, during its existence, Heiner housed people from across the country and world, including numerous immigrants, and influenced the 20th century development of Utah into a modern state.