Sharon S. Arnold

History Blazer, August 1995

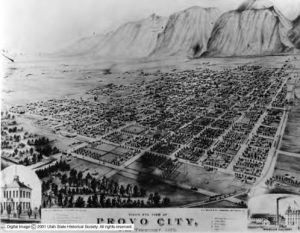

Bird’s eye view of Provo, Utah in 1878. Notable landmarks of the city were the Utah County courthouse and the woolen factory.

The Golden Spike was barely driven when pioneer leaders chose a likely site for a large factory. With the coming of the transcontinental railroad, the massive machinery needed to start large-scale manufacturing could be shipped to the territory, and local products could be sold from coast to coast.

LDS church leaders had a specific plan in mind: Sheep thrived on Utah’s landscape, and wool had been successfully processed in several small frontier towns. In addition, a mill site on the Provo River was available that could provide both water and power for wool-making. Provo’s residents were invited to cooperate in the enterprise by donating labor, materials, or cash in exchange for stock in the planned enterprise. With their support, Brigham Young, Abraham O. Smoot, and a handful of other leaders formed the Timpanogos Manufacturing Association, parent company of the Provo Woolen Mills.

Skilled builders from all over the territory helped the Provo settlers in the grand construction project. Material was mostly donated, and when resources ran short the city of Provo gave wheat for the workmen, and Utah County sold the courthouse, just east of the factory block, to the new corporation in exchange for stock. The cash for the machinery, which was ordered from Philadelphia, came from Brigham Young (then president of the company), the LDS church, and private individuals.

The resulting plant on the Provo mill run was remarkable. It occupied a block near the center of Provo city, with four buildings housing equipment that employed about 150 workers. Many of the first workers were recent immigrants who had learned their skills in British textile mills. Later, the Provo factory hired young women to run the looms. The mill operated for ten months of the year. Power came from several turbine wheels. Beginning in 1890 surplus power was sold to the city for street lights.

The main building of blue limestone was four stories high and had a turreted stairwell and a tin mansard roof. The first floor and most of the second floor housed looms. “Mules”–spinning mechanisms–occupied the third floor and the balance of the second. On the fourth floor were carding machines.

Two other two-story buildings of adobe were connected to the main building with covered railways. In one, the fleece was sorted, washed, and sometimes dyed before it was laid out to dry on wide platforms in the yard. The washing or scouring of the wool was an especially important process because the fleece contained natural wax and salt and foreign matter–dust, burrs, and mud–that amounted to 80 percent of the weight of the fleece. All of this had to be removed without damaging the soft wool.

The second adobe building was used for finishing. Here, cloth was checked for quality, washed again, fulled, and sheared in. In fulling, woolen cloth was moistened, heated, and pressed to shrink and thicken it. A final pressing in the finishing room made it smooth and glossy, or, in the case of blankets, another finishing machine raised a furry nap.

A third small adobe building, on the factory block next to the building where the wool was sorted, was also used for dyeing.

The fortunes of the mill ebbed and flowed. At first, it produced a full range of woolen fabrics that were loyally bought by Latter-day Saints. The cloth was extremely durable but not as finely finished as imported fabrics. Later, however, the factory specialized in heavier woolens: blankets, shawls, yarns, flannels, and doeskins. About one-third of these were exported, mostly to nearby states. Hart, Schaffner and Marx, a well-known men’s clothing firm, was an important customer. The Provo mills also made the carpet for the St. George Temple. In 1897 John C. Cutler and Brothers of Salt Lake, agents for the Provo mills, sold men’s suits for $7.50. Heber J. Grant told an LDS conference audience in 1910: “With one or two exceptions, I never wore a suit of clothes that was not made of cloth manufactured at Provo.”

In 1902 Reed Smoot, who had been the factory’s energetic and imaginative superintendent for several years, was elected to the U.S. Senate. This, combined with the problems of old machinery and increased competition from eastern mills, brought business to a halt. Machinery whirred into production once again in 1910 when Jesse N. Knight’s mining money bought the mill as an investment. It continued to operate until 1932, though its primary role in Utah’s history was long since played out, for decades earlier, major industry and commerce had become firmly established in the territory.

See Sharon S. Arnold, “The First Large Factory in Utah,” Beehive History 6 (1980).