The Peoples of Utah, ed. by Helen Z. Papanikolas, © 1976

“The Utes, Southern Paiutes, and Goshiutes,” pp. 27–59″

by Floyd A. O’Neil

“….. teach ’em to speak Ute. And don’t let them ever forget how we’re supposed to live, who we are, where we came from.”…Connor Chapoose

Confined on reservations, no longer free to range over the mountains and deserts of their lands in the incessant quest for food, the hard-pressed Utes never completely forgot how they were supposed to live, who they were, and where they came from. The elders handed this knowledge down to them in family tepees, during tribal ceremonies, and in the everyday practice of religion and acknowledgment of their myths. They knew that once their lands had stretched as far east to what is now the city of Denver, as far west to the Great Salt Lake Desert, and from northern Colorado and northern Utah south to the New Mexico pueblos. In these lands of mountains and deserts, the Utes were assured of ample food. The White River band of Indians hunted and fished in the Colorado Rockies and the Uintas during the summers while their women gathered seeds and berries. Buffalo meat was sliced thinly and dried; bones and marrow were boiled and ground into a gelatinous food; seeds were crushed into flour; and berries were dried, with part of the harvest pounded into dried meat (pemmican) and stored to be eaten in wintertime. The desert Indians ingeniously gathered myriad kinds of seeds and cacti to augment the large and small animals that were their main source of food. Not all of the Ute bands, however, were so fortunate as the Utes of the Utah Lake area who had an abundance of trout available as well as berries, seeds, roots, venison, and fowl; but as with most Indian tribes, they well understood the uses of the earth.

The shelters for the largest portion of the tribe were tepees, but brush and willow houses that were easily heated by an open fire were used as well. These structures were also cool in summer. One family might build several, depending on where they chose to live during that portion of the year: one at a fishing camp in winter, another near the place where seeds were gathered in July, another for the gathering of wild berries and fruits in August and September, and yet another in the pine forests where the women could gather the nuts and men could hunt in late summer and fail.

Their myths, together with their traditions, told the Utes how they were “supposed to live.” It was far from the stereotype of Indians as an aimlessly roaming people ruled by primitive whims, ruthless to their women, children, and enemies. The Utes used their territory with systematic efficiency for the gathering of food and for the comfort of the season. Economics determined that they live in small bands of probably fewer than two hundred people, except for the large encampment at Utah Lake. This allowed them to maintain their food supply without endangering the size of herds, the grasses, or plants on which they subsisted.

Long before white contact, the Ute people believed in the immortality of the soul. They believed in a Creator God, Senawahv, and other lesser gods?a God of Blood, healer of the sick; a God of Weather, controller of thunder and lightning; a God of War; and a God of Peace. The Ute people believed in the pervasive power of Senawahv who fought and won over evil forces, and therefore their view of life and afterlife was essentially optimistic. None of the religions of the people from the European continent has ever been successful in altering this view among the Ute people.

The religion of the Ute people has always been highly individualistic in its application. Group rituals were not common, although two celebrations, the Bear Dance and the Sun Dance, have remained important to the present day. The religion was dominated by shamans (medicine men), people possessing special powers. Persons sought through the shaman the power of the supernatural to help them gain good health, courage, ability in the hunt, and defense of the groups. The practices of the shamans were not alike, nor were they formalized systems. Each shaman acted, sang, and used items which were different for each occasion and each manifestation of power. Some items used regularly by the shamans were eagle feathers, eagle bones, fetish bags, and certain medicinal plants. In performing their acts, especially in healing, the shamans often used songs and prayer to assist them. The practice of using shamans’ services has increased in some of the Ute communities in the recent past.

The family was the center of Indian life and loyalty to it was the fabric of existence. The family included not only the immediate members as in European cultures, but extended to uncles, cousins, and maternal and paternal grandparents. Grandparents were extremely important for their judgment and for their intimate involvement in the rearing of children.

The honors extended to the aged were many–first to be served, seated in honored spots, and accorded special respect by the children. Work was expected of all, with the exception of small children. Prowess in hunting and defending the people was admired in men. In women, integrity, the ability to gather foods, prepare them, and the tanning and sewing of leather for clothing were admired traits. The woman who could feed, clothe, and shelter her family well was extended prestige. Babies were welcomed; theirkhans (“cradle boards”) were decorated with beaded flowers and rosettes in blue for girls and often butterflies and rosettes in red for hays. The aromatic smooth inner bark of cedar was shredded for use as diapers.

The songs and stories of the people were the entertainment and the learning systems of the Utes. An infinite number of stories were told, some for moral instruction, some of bravery, some illustrative of the foolish acts of men, while others were of lyrical beauty describing nature as the handiwork of God. The stories and songs provided a milieu for nearly every act: birth, reaching manhood or womanhood, going to war, marriage, or death. Each storyteller and singer of songs had his own style and variation of which he was proud.

Surrounded by a large family, a plentiful earth ruled over by a beneficent God, the Ute child grew to maturity in a world where he felt himself an integral and welcome part.

Beyond the family, leadership was shared by many people rather than a “leader” in the commonly held sense of the word. Leaders were chosen from time to time to perform duties such as to lead a war party in defense of the Ute domain, or to lead the hunt for food. The most common form of leadership was simply respect for the wisdom of the elders of the tribe who assembled and came to decisions concerning matters. Following European contact, persons who were chosen to perform certain duties for the tribe were assumed by outsiders to be chiefs or rulers. They were not. They were respected members of the tribe performing certain functions.

Women, too, were given leadership roles. Chipeta, the wife of Ouray of the Uncompahgre band, is one of the celebrated women in the history of Colorado and Utah. John Wesley Powell was impressed with chief Tsau-wi-ats’s wife and wrote in his journal:

His wife, “The Bishop,” as she is called, is a very garrulous old woman; she exerts a great influence, and is much revered. She is the only Indian woman I have known to occupy a place in the council ring.1

This ordered life began to change, imperceptibly, with the coming of the first Europeans into their territory. The Utes received many goods of great value from the Spanish: metal points for arrows, metal cooking pots, mirrors, guns, and most important, the horse. They enjoyed an additional advantage: since the northward thrust of the Spanish empire stopped at the edge of Ute territory, they, unlike the Pueblo people, did not endure Spanish and Mexican administration.2 The advantages of trade were also broadened. Even though the Utes had traded at Taos and other pueblos for generations prior to the arrival of the Spanish, their wealth now grew with the Europeans’ increased demand for meat and hides that were bartered at Taos.

Although the Spanish drive to the north stopped at Abiquiu in the Chama Valley, its influence was felt much farther. Some trips were made into Ute country: in 1765 the Rivera expedition to the Uncompahgre River in Colorado; the Dominguez-Escalante journey mostly through Ute country in 1776; the Arze-Garcia expedition of 1813; and many journeys to Ute country by one Maestas who was interpreter and legal officer on the northern frontier for Spain and later Mexico. These and other incursions were but momentary, however, and the integrity of Ute territory was maintained.

In the 1820s, when the Santa Fe Trail from Missouri to New Mexico was opened, some of the people who came to New Mexico were men interested in fur trapping. From Santa Fe and Taos the trappers moved northward into Ute country to gather the furs from the mountains the Utes called home.3 Also coming from Missouri were trappers who moved directly into Ute country from the east and north. Those who came from Missouri up the Platte River route into Ute country became legendary figures in the early history of the West: William Henry Ashley, Jedediah Smith, Jim Bridger, Thomas Fitzpatrick, and Thomas L. (Pegleg) Smith, to name a few.

The trappers who came from Taos and Santa Fe also left their mark on the land: Antoine Robidoux, Etienne Provost, Denis Julien, and the elusive Duchaine. Elderly Utes of today recall hearing about them: “. . . my mother [said] Chambeau Reed? had his first trading post at Whiterocks. ? He traded calico, beads, knives, and stuff like that to the Indians, and buckskin and furs.”4

During the time of the fur trappers, a commercial route of lasting import was opened through Ute country in the early 1830s: more than half of the Old Spanish Trail from Santa Fe to Los Angeles led through Ute lands, with an additional portion through Paiute lands in Utah.5 During the 1820s to the 1840s, the Utes began experiencing an increasing number of intruders who sought their resources. In the 1830s the Missouri French fur traders working from Taos opened two trading posts in Ute country, one m the Uinta Basin and one on the Uncompahgre River in Colorado.

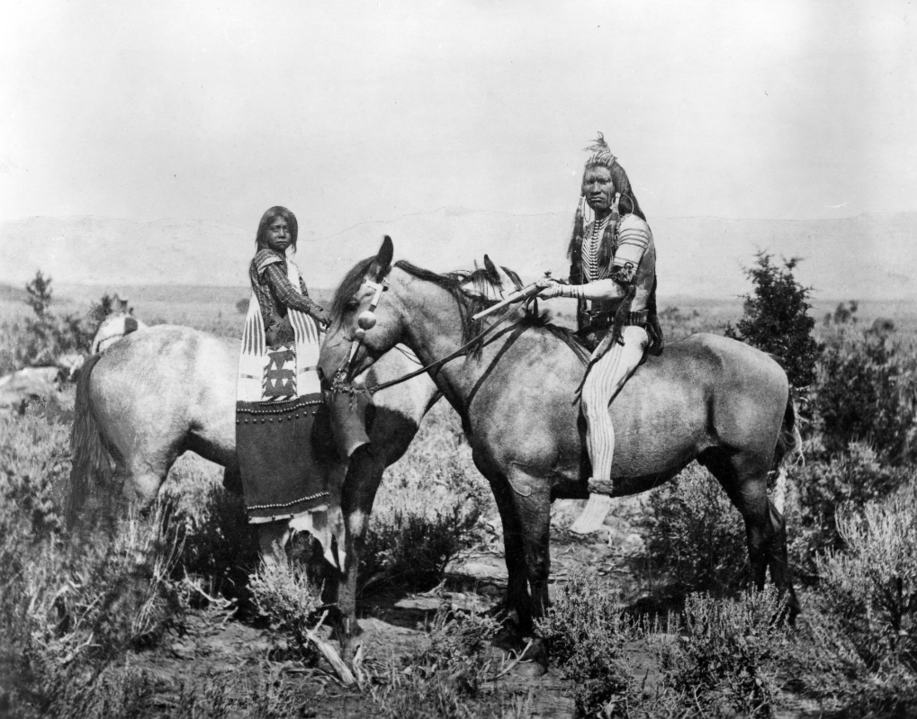

A Ute warrior and his bride in the Uinta Valley, ca. 1873

Then, in the 1840s, two events changed Ute life forever. The first was the rapid defeat of the Spanish-speaking people to the south. The Mexican War altered the powerful force with whom the Utes had traded and made treaties. Secondly, the Mormons arrived in Ute borderlands and began a rapid dispersion of their people into the most fertile areas of the western fringe of Ute lands. Game, wild berries, and roots that Utes depended on for food became depleted. The pioneers hunted the game for themselves and they uprooted the roots and fruit-bearing bushes to cultivate fields.

The Americans moved rapidly. In the first decade following the Mexican War, they defeated the Ute bands who opposed them, founded Fort Massachusetts in southern Colorado, placed a military force on the northern border with two forts in Wyoming, and started the occupation of the lands in Colorado.

In all of this, the Utes remained remarkably peaceful. Only the Walker War in Utah and some raiding on the northern New Mexico-southern Colorado border by the Utes were exceptions. These breaches were experienced only after great provocation.

For the Utes, the occupation of the lands was troublesome on the eastern front, troublesome in the south, but fraught with disaster in Utah. By the winter of 1856 starvation had begun.6 Brigham Young said, soon after the Mormons settled in the Salt Lake Valley:

When we came here, they could catch fish in great abundance in the lake in the season thereof, and live upon them pretty much through the summer. But now their game has gone and they are left to starve. It is our duty to feed. . . these poor ignorant Indians; we are living on their possessions and in their homeland.7

Although some charity was given, the settlers ignored the basis for Indian raids that “Indians… rapidly reduced to a point of starvation followed nature’s law which predicates that a hungry man always goes in search of food and will follow the course which promises the most speedy relief.”8 Instead, most settlers looked on the Indians as mere thieves. A Deseret News article was typical of this attitude:

The Indians in and about Cache Valley are represented as being considerably inclined of late to be saucy and belligerent in their deportment, and have committed some depredations and threaten to do more. They are reported to be unusually fond of beef, which if they cannot get in one way, they will take in another.9

Inadequate federal response to the Indian agent’s appeals for food and funds coupled with the dramatic rise in Utah’s population spelled trouble. The Indian farms in central Utah, which had been started in the 1850s, were closed by agent Benjamin Davies and all furnishings sold to feed the starving Utes. The agent at the time described them as being in a “state of nakedness and starvation, destitute and dying of want.” 10 Even the conservative historian Bancroft observed, “The natives had no alternative but to steal or starve; the white man was in possession of their pastures; game was rapidly disappearing, in the depth of winter they were starving and almost unclad.. . .” 11 The Utes increased their raids on cattle and other livestock of the Mormon settlers. The answer in Utah to this situation was expected: the populace demanded the removal of the Indians.

The location was anticipated to be the Uinta River Valley. Before the designation was made, however, the Mormons explored it to see if they wanted it for themselves. They rejected the areas as too poor for white settlement.12 It took only six weeks after the Mormon rejection of the area for Indian Affairs officials to persuade President Abraham Lincoln to set it aside as a home for the starving Utes, October 3, 1861. But Congress was slow to ratify Lincoln’s designation; not until May 5, 1864, did the confirmation come, and by then many Utes had died of starvation. Federal responsibility was not fulfilled for several reasons: Congress was penurious, cabinet officials did not grasp the problems, and the energies of the federal government were directed toward survival in the Civil War. The problem was so great that the occasional charity given by settlers and institutional efforts were unequal to a solution.

The Mormon settlers pressed to have the Indians removed. Naturally, the Indians resisted leaving the areas of Provo, Spanish Fork, and Sanpete for the bitter cold of winter and the small food supply of the Uinta Basin. Indian resistance gathered behind a new leader named Black Hawk, a man recently raised from obscurity. By 1865, when the Civil War had ended and the United States government could direct its officers to settle the Indian question in Utah, the Black Hawk War had reached serious proportions. It was to be the largest and costliest war in Utah history. The Mormon settlers were forced to abandon entire counties, build forts, and raise and maintain a levee of troops in the Nauvoo Legion. Because the conflict was mainly over raids on livestock herds, the guerrilla nature of the fighting was a war of attrition on both sides.

In the long run, the technical ability, the supplies, and the superior numbers of the whites made the outcome an. inevitable Indian defeat. In 1865 a hope for peace came when 0. H. Irish offered a relatively good treaty to the Utes to induce them to move. Brigham Young was at the treaty negotiations and urged the Utes to leave. But Congress never ratified the treaty, and the native people felt betrayed. This failure by Congress added fuel to the resistance which was already afire across the territory of Utah.

After another series of raids the Utes were defeated, and Black Hawk was replaced by a man who recommended peace–Tabby-to-Kwana (“Child of the Sun”). He led the reluctant and defeated Utes to the Uinta Basin; there they found almost no preparations had been made for their coming. As the raids renewed, Brigham Young gathered up about seventy-five head of cattle and had them driven to the new reservation. The act helped to stop the raiding.

Within the boundaries of their new, inhospitable domain, the quality of Ute life changed. Symbolic of the whole was the replacement of wild game, berries, and roots with a weekly government ration issued for each family.

A typical allotment was as follows:

| Bean coffee | 2 lbs. | Bulk soap | 1/2 lb. |

| Bulk lard | 2 lbs. | Sugar | 2lbs. |

| Salt bacon | 2 lbs. | Salt | 1/2 lbs. |

| Flour | 10 lbs. | Fresh beef | 10 lbs. |

| Navy beans | 2 lbs. |

13

As Frank Beckwith said in his small treasure, Indian Joe, the Utes traded their ancestral lands for “beef, sugar, and a blanket.”14

The first Indian agents were disappointed with their situation and refused to stay. In 1871 John J. Critchlow came to the Uintah Reservation and for the next decade moved with relentless energy to make the reservation a home for the Utes and to induce them to farm. He founded a sawmill, invited traders to come from Kentucky to open trading posts, increased the size of the cattle herds, established a day school, broke new lands for agricultural pursuits, and distributed supplies carefully until the agency could be nearer to self-supporting. The Utes came to trust him and were in far better condition when he left than when he took up his labors there.

Most of the Utes from central Utah became firmly planted in their new home, although a few small groups remained on the fringes of Mormon towns.15 But barely a decade of troubled peace was allowed to the Utah Utes when events again radically altered their situation. The Utes in Colorado had been given a treaty in 1868 in which they held about one-third of western Colorado. Then gold was discovered in southwestern Colorado, and the government renegotiated for a quadrangle of land in the San Juan Mountains for the gold and other minerals there. The Utes were reluctant, but the pressures on the United States government were so great that their giving up of this land was inevitable. The “Bruno Cession” occurred in 1873.16

The increased population and power of Colorado Territory were recognized by the federal officials, and statehood was granted in 1876. The citizens of this new state were unwilling to accept the idea that nearly one-third of their territory was still Indian reservation. A demand that “the Utes must go” soon developed into a statewide movement.17

That opportunity came in 1879. The Utes of the White River band had been dissatisfied with the effort of their agent to get them to farm. The agent, Nathan C. Meeker, was a figure of national reputation who had been a writer, journalist, and Socialist experimenter. He was a friend of Horace Greeley and had named a Socialist community in Colorado after him. When the Greeley colony failed, Meeker decided to reform and remake the Utes into farmers after his design. He ordered them to sell their beloved ponies and began to plow up their pasture to plant crops. The Utes fired on the plowman. Instead of negotiating with his wards, Meeker sent for troops. The Utes warned that if the soldiers came on the reservation, war would ensue; the White Rivers were known to be more warlike than other Ute bands.

The detachment from Fort Steele, Wyoming, under the command of Maj. Thomas Thornburg moved close to the White River Agency. The Utes attacked under their powerful leaders: Captain Jack, Douglas, Chief Johnson, Atchee, and Sow-a-wick. In the battle, Major Thornburg was killed and his troops surrounded. The Utes moved back to the agency where they killed twelve people, including Nathan Meeker. A second force was then sent to relieve Thornburg’s trapped men. At that time a leader of the neighboring band of Utes, Ouray, intervened and persuaded the White River Utes that the whites had too many soldiers to resist. Peace was restored, captives returned, and officials descended upon the scene for the inevitable readjustment.18

“The Utes must go!” the crowd demanded. The White Rivers were forced to leave Colorado and take up residence on the Uintah Reservation in Utah. Ouray, who had long befriended the whites and who had mediated to stop the battle with Thornburg’s troops, was similarly punished. Ouray (“Arrow”) spoke four languages: Ute, Apache, Spanish, and some English. As a result of his linguistic ability, he had been chosen as a negotiator in dealing with the white men, who immediately began referring to him as “chief.” (Later he assumed a more important role in tribal affairs internally because many of the tribal interests at that time involved dealing with outsiders. Ouray has been given far more importance in histories written by whites than the Ute people assign to him.) He and his Uncompahgre band were forced from their homes to the Utah lands. Ouray died before the exodus began and Sapavanaro and Guero replaced him. Around these new leaders was a group of strong men, capable of leading: Billy, Wass, Peak, Curecante, McCook, Cohoe, Chavanaux, Red Moon, Unca Sam, Alhandra, Wyasket, and Ar-reep.

Sapavanaro and Guero rode with military personnel out of the home they had always known, out of Colorado toward the Uintah Agency to search for a place to put more than one thousand Utes.19 The military men selected the Uncompahgre Reserve by simply riding down the White River to the Green River. The river valleys into which the Uncompahgres were to be sent were but narrow ribbons of green through an expanse of poor desert land almost bare of vegetation. The choice was made hastily and without any real knowledge of the country.

Rather than move there, the Utes attempted to negotiate with the army–to no avail. Capt. James Parker of the Fourth Cavalry reported:

After a debate lasting several hours they sent for Mackenzie. They proposed a compromise. They said they had concluded they must go, but first they had wished to go back to their camp and talk with their old men. “No,” said Mackenzie. “If you have not moved by nine o’clock tomorrow morning, I will be at your camp and make you move.”

The next morning, shortly after sunrise, we saw a thrilling and pitiful sight. The whole Ute nation on horseback and on foot was streaming by. As they passed our camps their gait broke into a run. Sheep were abandoned, blankets and personal possessions strewn along the road, women and children were loudly wailing.

…It was inevitable that they should move, and better then, than after a fruitless and bloody struggle. They should think, too, that the land was lost beyond recovery.

…As we pushed the Indians onward, we permitted the whites to follow, and in three days the rich lands of the Uncompahgre were all occupied, towns were being laid out and lots being sold at high prices.20

The Uncompahgres were moved from the high San Juan Mountains of Colorado, the “Switzerland of America,” to their desert. The shock embittered them. Little had been done to found an agency at Ouray, and so it was decided that extra efforts–a new military post–would be needed to keep the Utes on their new reservation. To guard the Indians, Fort Thornburg was founded across the river while the new agency was being constructed. The Utes had received what was to be their permanent home. The location of the fort was seen to be a threat to the peace of the area, and it was moved to a site near the mouth of Ashley Creek Canyon. There it existed for three short years and was abandoned in 1884.

Almost from the day of the founding of the Uncompahgre Reserve the agents there complained bitterly of the location. One agent described the land as

extremely rugged and fearfully riven, being pinnacled with mountains, crags, and cliffs and torn with canons, arroyos, and ravines…. a wild and ragged desolation, valuable for nothing unless it shall be found to contain mineral deposits.21

As poverty and starvation deepened, the Utes began to return to Colorado to hunt, causing a great outcry. In addition, they would not send their children to school or adapt to what Secretary of War L.Q.C. Lamar called “civilized pursuits.” 22 Using this as a pretext, Lamar ordered Fort Duchesne to be founded in September 1886. The Utes were angered at the arrival of troops but decided that resistance was useless.

In 1886, with the new fort in existence, the Uintah Agency and the Ouray Agency were combined and the agent moved to Fort Duchesne. From that day to this it has been known as the Uintah-Ouray Agency. Yet, only one year after the founding of Fort Duchesne and the consolidation of the agencies, Congress passed the Dawes Act designed to break up the reservations and to make Indians into individuals farmers. The Uintah-Ouray Reservation had hardly been founded when the dismantling began. Additionally, a hydrocarbon mineral called gilsonite was discovered in the northeastern corner of the reservation, and powerful new voices were added to demands that the Indian people be removed from that spot. In the early 1890s a large portion of the Uncompahgre band was allowed to take up farmlands along the Uinta and Duchesne rivers in the old Uinta Valley reservation.

Some of the new lands given the Uncompahgres were lost to white settlers by 1898, and seven years later, despite loud protests and threats by the Utes, the bulk of the reservation was opened by Congress to white settlement in 1905. Under Red Cap’s leadership, with the assistance of two other White River Utes, Mosisco and Appah, nearly four hundred Utes traveled from Utah to South Dakota hoping to make an alliance with the Sioux to war on the United States. But the harsh memories of Wounded Knee and the total poverty of the Sioux made the entire venture hopeless. Two years later, even more ragged, they returned home, escorted by the United States Army, to face their fate as reservation Indians surrounded by whites.23

The white settlers were never satisfied with the Indian land given them. They wanted more of it, for they could get the water shares necessary for cultivation while the Indians could not. The Pahvants at Kanosh, for example, were entitled to 120 shares of water for their 3,200 acres but for all their efforts were never able to get more than 20.

When the Ibapah Indians met in the Capitol Building of Utah this spring with the assistant Attorney General, seeking their rights, complaining about encroachments by whites on their farms, their water rights, their hunting, they referred to a specific treaty, “Indians remember it?but white men forgot it. . .

A white woman storekeeper at Kanosh was drawing gas for my car; I inquired: “Are the Indians making their farms pay” “No, and never will. Why don’t they give that land to us who want it, and go to the reservation and let the Government take care of ’em? Why they’ve even got 3,200 acres! We could do something with that!”

(Yes, 20 shares of water, and 3,000 acres of mountain tops. . .) 24

The Indians continued to be the dispossessed in all areas of life: property, education, and employment. The old saying “the only good Indian is a dead one” dogged Indians throughout their poverty-blighted lives. During the Great Depression they were refused WPA work. Their children were neglected in schools, their culture arrogantly dismissed. Struggling to keep their pride in being Indian, they have tenaciously held on to their culture and their religion.

However, since the arrival of the Europeans, Christian churches of the Episcopal, Catholic, and Latter-day Saints faiths have won converts. A further influence, the Native American church, was brought to the Uintah-Ouray Reservation in the early years of the twentieth century. This “peyote” church has had a strong effect on the Utes and is renewing its strength after some decline during the quarter century after 1940.

The ancient rituals continue to be held; the oldest is the Bear Dance in spring, at about the time bears leave hibernation. The dance takes place within a large circle made from willows and brush. All ages join in. The music comes from native instruments or modified ones using modem materials. The men and women form separate lines, face each other, and move back and forth in unison to the rhythm of the drums and the singing. The singers are usually women. But the Bear Dance is more than just a dance. It is a festival, a time of great socializing; card playing, hand games, and courting are carried on. Feasting and visiting last into the night.

The ritual having the greatest influence on the present-day Utes is the Sun Dance. This important celebration was introduced by tribes from farther north about 1890. The dance is an elaborate ceremony associated with gaining power or regeneration. It lasts for four days and nights, and the dancers neither drink nor eat during this time. The ceremony is a combination of ancient Indian and Christian symbolism. A permanent site for the Sun Dance has been established near Whiterocks, Utah. A twenty-acre plot holds the ceremonial edifice as well as providing room for the scores of tribal members who camp at the site. The dates of these summer dances vary, but July is more often the time for the event than June or August.

Since the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, the tribe has held periodic elections. Two members of each of the three bands are elected to govern the tribe. The elected committee then chooses a chairman who serves as the executive officer of the Utes. Women have also served on the Tribal Business Committee which has governed the tribe since 1936.

The present condition of the Utes of Utah is by and large far better than the condition of most other American Indian tribes, especially in economic pursuits. They own a substantial reservation with income derived from oil and natural gas leasing, from an impressive cattle industry, a furniture factory, and a major tourist facility called Bottle Hollow Resort. Great strides have recently been taken by the tribe in providing houses for their members. Several housing complexes have been completed in the past decade, and the standard of living has sustained a sharp upward trend.

In education, many of the Ute students are enrolled in the public schools of the Uintah and Duchesne school districts. However, many families prefer to send their children to all-Indian boarding schools provided by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, such as the Intermountain School at Brigham City, Utah; the Stewart School at Carson City, Nevada; Haskell in Kansas; and the Institute of American Indian Arts at Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Education, economic stability, social and legal justice, and the maintenance of the Ute culture remain as basic challenges to the Tribal Business Committee and the Ute citizenry at large.

The Southern Paiutes

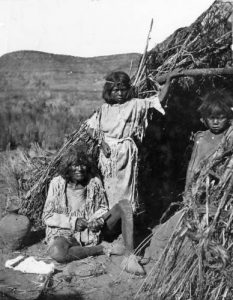

Paiute woman and children

In Spring and Summer the Pahutes lived in the valleys of the red mountains where they planted corn, beans, and grass seeds. In Fall they harvested, held a feast to thank their gods Tabats and Shinob for their bounty, and lived in mountain caves during Winter. The rains and snows diminished. Seeds, corn, beans, and grass plants withered for want of water. The bountiful animals, deer and elk; the smaller ones, squirrels, rabbits, chipmunks; the wild fowl fled. The starving Pahutes called their gods for food. Shinob answered, “You should have as much sense as the animals and birds. The country is large and somewhere there is always food. If you follow the animals and the birds they will lead you to it…

From that day to this the Pahutes have been a nomadic people. Leaving their homes in the caves, they have followed the game from high land to low and gathered in gratitude the foods which the gods distribute every year over the face of tu-weap, the earth.25

The country that the god Shinob told the Shoshonean Paiutes about was large, encompassing extensive parts of southern Utah, northern Arizona, southern Nevada, and southeastern California. Throughout it, the Paiutes hunted, gathered, and farmed small plots. They organized themselves loosely into bands of several families, each of which controlled a definite territory. There was little or no tribal organization, although several bands or band members might temporarily join together for a certain project. The Paiutes were slow to acquire and effectively use horses. (When they did come into possession of one, they usually killed and ate it.) As a result they became victims of the Utes who raided them on horseback and captured their women and children as slaves, either for themselves or to be sold to the New Mexican Spanish settlements.

Some Paiutes who lived southeast of the Colorado River visited the Spanish settlements before 1776, but the central body of Paiutes living on the tributaries of the Virgin River -first encountered white men when the Dominguez-Escalante expedition crossed their lands on their return to Santa Fe. Father Escalante wrote of coming upon women who were gathering seeds and were

so frightened that they could not even speak.... we saw other Indians who were running away…. We did our best to know what kind of people those were who already planted corn…26

In the interim between the Escalante expedition and the beginning of commercial traffic on the Spanish Trail, the Spanish began to take a more active role in the slave trade, penetrating deep into Ute country to buy Paiute slaves. The successful establishment of the Spanish Trail that ran directly through the heart of Paiute country made the slave trade an important part of Spanish-Indian relations. In 1843 Thomas J. Farnham wrote of the slaves:

These poor creatures are hunted in the spring of the year, when weak and helpless… and when taken, are fattened, carried to Santa Fe and sold as slaves.

To elude capture the Indians carried water with them and avoided springs.27

Although the Paiutes partially retreated from the areas the whites had invaded, the aggressiveness of American trappers and explorers who began to enter the area in the 1820s forced the relations between Paiutes and whites to a low point. This was the condition when the Mormons arrived in Utah. The Paiutes experienced the usual displacement from their best hunting and gathering lands. Grazing animals, timbering, and cultivation drastically cut their food supply.

One of the first outer settlements established by the Mormons was located at Parowan, well within Paiute territory. By that time, the Paiutes had attained the reputation of being hostile, but the Mormons were able to establish peaceful and secure relations with them because they provided a buffer against Ute and Spanish raids, supplied trade that increased material wealth, and introduced productive fanning methods.

The Mormons came from a religious culture that emphasized a special role for Indians (the Lamanites of the Book of Mormon), and the Paiutes were an easily controlled group upon which these beliefs could be practiced. One of the earliest, largest, and most successful Indian missionary efforts was called the Southern Indian Mission established at Fort Harmony, south of Cedar City in 1854.

Missionary work, principally by Jacob Hamblin and Howard Egan, kept confrontations from becoming serious. John Wesley Powell records in his journal:

This man, Hamblin, speaks their language well, and has a great influence over all the Indians in the region round about. He is a silent, reserved man, and when he speaks, it is in a slow, quiet way, that inspires awe… . When he finishes a measured sentence, the chief repeats it and they all give a solemn grunt….

Then their chief replies [to Powell]: “Your talk is good, and we believe what you say. We believe in Jacob…… When you are hungry, you may have our game. You may gather our sweet fruits. We will show you the springs, and you may drink; the water is good .. We are very poor. Look at our women and children; they are naked. We have no horses; we climb the rocks, and our feet are sore. We live among the rocks, and they yield little food and many thorns. When the cold moons come, our children are hungry. We have not much to give; you must not think us mean…. We love our country; we know not other lands. We hear other lands are better; we do not know. The pines sing, and we are glad. Our children play in the warm sand; we hear them sing, and are glad. The seeds ripen, and we have to eat, and we are glad. We do not want their good lands; we want our rocks, and the great mountains where our fathers lived…28

In addition to converting the Indians to Mormonism, the Mormons also sought to end the New Mexican slave trade. This came about in 1852 through an act of the Utah territorial legislature that substituted indentured servitude for slavery, a system that was in practice limited to Mormons. The slave trade decimated the Paiute population; the Mormon version of servitude continued the process. Although generally treated well, the Paiutes who lived in Mormon houses were torn between two cultures. They rarely married, but those who married whites had children who most often considered themselves whites. Hence, the Paiute population declined further. The diseases which the whites brought with them continued the process of shrinking the Paiute population, and by the 1890s it was difficult to find any survivors at all of a majority of the original Paiute bands.

Although Paiutes continued to have skirmishes with travelers on the Spanish Trail and occasionally even with Mormon settlers, their dwindling population usually came under domination of the white settlement nearest them. The establishment of the first Southern Paiute Agency at Saint Thomas in 1869 and also the Moapa Indian Reservation in 1873 resulted from tensions between the Nevada Paiutes and miners when mineral discoveries were made in Meadow Valley and Pahranagat Valley in the late 1 860s and early 1870s.

The problem then arose of removing all the Southern Paiutes to a reservation in accordance with current government policy. In 1865 a few Utah Paiutes had signed a treaty relinquishing southern Utah in return for their removal to the Ute reservation in the Uinta Basin. This treaty had never been ratified, but, nevertheless, it became the basis of government policy. John Wesley Powell and George W. Ingalls were sent to the area to determine Paiute status. In 1873 they recommended that all of the Southern Paiutes be removed to Moapa. This policy was continued for the next decade. Either through lack of interest or forgetfulness, the government neglected the Indians for many years.

With lack of supervision and aid, the Moapa reservation sank into corruption and neglect. Occasional government inspections found the reservation almost totally abandoned by the Paiutes who had become an integral part of the local white economy by providing a cheap labor force. Jacob Hamblin wrote to Major Powell in 1880 of the Paiutes’

destitute situation….The watering places are all occupied by white man. The grass that product mutch seed is all et out. The sunflowere seed is all destroyed in fact thare is nothing for them to depend upon but beg or starve.. .. I assisted them some this last season to put in some corn and squash. They got nothing on account of the drouth. They are now living on cactus fruit and no pine nuts this season.29

In 1891 the government provided a reservation for the Southern Paiutes in an area cut through by the Santa Clara River. This location had historically supported one of the largest segments of Paiute population. However, this reservation did not provide for the Tonoquint or Paroosit Paiutes who had once farmed its bottom-lands. It did provide for the remainder of the Shivwits Paiutes who lived deep in the Arizona Strip on the Shivwits Plateau near the Grand Canyon. There were not enough living members of the other bands to even perpetuate their names.

In the early part of the twentieth century a partial attempt was made by the government to regain control over Indian affairs at Moapa. Land was acquired at Las Vegas for an Indian colony, and the Moapa Agency was temporarily moved there in 1912. Other Paiute reservations were established: the Kaibab Reservation in northern Arizona in 1907, the Koosharem Reservation in central Utah in 1928, and the Indian Peaks Reservation in western Utah in 1915.

A colony of Paiutes had existed at Cedar City since the Mormons first settled there in 1851. The government twice offered to buy land for these Indians, but the local residents replied that they would provide the land.

The twentieth century has not changed the relative economic standing of the Paiutes significantly. The Indians who work are still mainly limited to manual labor; most depend on welfare to some degree for sustenance. Only on the Moapa and Kaibab reservations has there been much success in establishing a healthy economic community. The United States government has also largely continued its traditional role of ignoring the Indians and their problems. This practice had its logical conclusion in 1957 when the Southern Paiutes of Utah had their special trustee relationship with the government terminated. They had become the victims of a government policy advocating immediate Indian integration into the general American culture and economy. Although the Paiutes had been judged unready for such termination by preparatory reports, they were one of the first tribes to go through the process. Of the Utah Paiutes, only the Cedar City band escaped this fate, probably because they did not own any land.

The Southern Paiute land claims decision of 1965, a controversial case that was settled out of court without even the normal determination of date of taking or territorial boundaries, partially repaid the Paiutes for the land they had lost. However, money could never begin to restore the Paiutes’ lives, peace, and pride that had been gradually but relentlessly destroyed in the face of white advancement into their territory.

For all their adversity, the Paiutes can still say as did the old chief to Major Powell: “We love our country; we know not other lands.” Federal and state training programs have been unsuccessful because they require relocation that threatens close family ties. Still, the native language is heard less today. Fewer religious beliefs are retained, but herbs for medicine and berries and pine nuts for food are still gathered. Summertime is also visiting time, as it has always been, and families travel long distances to attend rodeos and Ute Sun Dances and Bear Dances. But many Paiutes no longer know that when their people were as free as the eagle, their costumes were adorned with its feathers. Now turkey feathers are used. “The young, they go away to school. They forget. They need to spend more time with their elders, learning, listening. They talk about their heritage but they don’t want to take the time to really feel it.” 30

The Gosiutes

Early travelers through Gosiute country, southwest of the Great Salt Lake, were appalled at the small tribe’s miserable existence and amazed that human beings could survive in that desolate country of alkaline earth and sagebrush. Mark Twain wrote:

we came across the wretchedest type of mankind… I refer to the Goshoot Indians… [who] have no villages, and no gatherings together into strictly defined tribal communities–a people whose only shelter is a rag cast on a bush to keep off a portion of the snow, and yet who inhabit one of the most rocky, wintry; repulsive wastes that our country or any other can exhibit.31

Capt. J. H. Simpson, exploring the Great Basin in 1859, was repelled by the Gosiute food of crickets and ants, rats and other small animals; their scrawny nakedness; and their dogged clinging to life. They illustrated, he said, the theory that man’s terrain is “intimately connected with [his] development….” 32

The Gosiutes had no horses; their shelters in the summer heat and winter cold were made of piled-up sagebrush called wickiups. They used twine to bind juniper and sage, as well as rabbit skins, to make blankets. Moccasins were a prized rarity. Explorers thought of the Gosiutes as near-animals and were surprised when they showed human emotions.

These Indians appear worse in condition than the meanest of the animal creation. Their garment is only a rabbit-skin cape… and the children go naked. It is refreshing, however,. . . to see the mother studiously careful of her little one, by causing it to nestle under her rabbit-skin mantle.33

The same explorer gave bread to

a very old woman, bent over with infirmities . . . and the most lean, wretched-looking object it has ever been my lot to see. . . . [Although the old woman] was famished, it was very touching to see her deal out her bread, first to the little child at her side, and then only after the others had come up and got their share, to take the small balance for herself.34

With hunger a constant, the Gosiute birthrate was low, keeping the tribe at several hundred in number. They survived through the ingenious use of the desert wasteland.35 Their entire lives were devoted to the search for food, leaving hardly any time for ceremonies. Only the round dance was known, a sideways shuffling to the beat of a drum, an invocation to make grass seeds grow; at infrequent times it was also a social. dance. Because they were constantly moving in their food search, their possessions were few: baskets to collect seeds, knives and flint scrapers to skin and dress the small animals, and grinding stone for crushing seeds. Except for communal animal hunts, each family moved alone in its gathering of food, and this made solidarity and tribal development impossible.

The Gosiutes exploited the desert to its fullest. They used eighty-one species of wild vegetables: forty-seven gave seeds, twelve berries, eight roots, and twelve greens. The most important food was the pine nut. Large quantities were stored because it was not an annual crop, and when it failed starvation neared. A good crop meant a good winter.

It was in winter when seed gathering could not be done that the Gosiutes huddled in their sagebrush wickiups and told their myths.36 Summer was not the proper time for telling myths; it was even dangerous to do so. Hawks and coyotes were actors in many of the myths. Coyote was feared and even when starving, the Gosiutes would not eat its flesh. It was a quarrel between hawk and coyote on a large mountain that formed the mountains of Gosiute land. In anger hawk flew high, then swooped down on the mountain and clawed it, breaking off the top and scattering it into smaller mountains. Besides animal myths, there were stories of “Little Man” who gave shamans power and “Water Baby” who cried at night but disappeared by day. In the winter, also, a few simple games were played: hoop and pole game, hand game, and races.

In the harsh life of the Gosiutes, communal hunts were exciting events. The most common game pursued was the black-tailed rabbit. Hunts for antelope were not held yearly because they greatly reduced the herds. Preparation for an antelope drive brought several families together to erect mile-long, V-shaped traps of stone and sagebrush under the medicine man’s direction. Twenty miles away from the mouth of the trap, hunters stationed themselves and slowly converged toward it. Antelope would run from the hunters toward the trap. They would then be enclosed in the small end where a few at a time would be taken out, killed, the meat dried, and the skins tanned.

This barren, simple Gosiute life was destined to change when Capt. Howard Stansbury, surveying for the Corps of Topographic Engineers, built an adobe house in Tooele Valley. Timbering began nearby and a mill was built. By 1853 there were farms surrounding the townsite of Tooele and the cycle began: settlers invading Indian regions and uprooting the land to make farms; their cattle, sheep, and horses eating the grasses that the Indians needed for seeds; and the Indians retaliating by raiding the settler’s livestock.37

An incident during these first years when whites began crossing Gosiute lands has become legendary. Capt. Absolom Woodward’s company of ten men had camped in Ibapah land (“Deep Water” or “Deep Creek”) near a cluster of Gosiute wickiups. Four soldiers were later discovered killed, food for scavengers, and the mail they were transporting strewn over their bodies. Rumors that the killings were not senseless acts of the Gosiutes but motivated by revenge continued for decades. An amateur historian, James P. Sharp, attempted for years to learn the truth behind the rumors, but the Indians would tell him nothing. He had his opportunity when an old Indian, Antelope Jake, came to ask him for work. Sharp knew that Antelope Jake was said to be one of the men who had killed the soldiers and hired him as a sheepherder. While gaining his confidence, Sharp found that Antelope Jake was fond of canned tomatoes. Taking four cans with him, he visited Jake’s sheep camp and displayed them. He soon had Antelope Jake’s story: the soldiers camped near the wickiups had learned that the tribe had gone antelope hunting and had left their girls behind to tend the elderly and the small children. They raped the girls and moved on. When the tribe returned, six of the men on foot, armed with bows and arrows, stalked the company through falling snow, hiding on the mountain slopes, knowing that they were no match for men armed with guns and riding horses. They ambushed five of the men in a mountain draw; one escaped and rode on to spread the story of wanton murder.38

Indian raids in search of food became more frequent. To put an end to them, Robert Jarvis, an Indian agent, tried to convince the Gosiutes to learn farming. One of the hands had already plowed the ground by using sticks and had planted forty acres of wheat, but most of the Gosiutes were unwilling to give up their traditional life. To prevent further raids, the government and the mail company provided provisions for the Indians who, however, were not placated. They killed three employees and wounded another during the winter of 1862-63. A treaty that followed gave the president of the United States the right to remove the Indians to reservations, but when the Uinta Basin was chosen for the relocation of Utah tribes and most Indians submitted, the Gosiutes refused to leave their land.

Federal annuities continued for the Gosiutes; their game was gone and their territory reclaimed for farms. Again farming was tried, but the wheat crop was destroyed by grasshoppers. Further efforts were made to induce the Gosiutes to move to a reservation but they were afraid, they said, of living among other Indians. Only the Gosiutes in Skull Valley had had success with farming, entirely through their own efforts. The government had given them no help and continued to press for the removal of all Gosiutes to the Uintah Reservation although the tribe repeatedly avowed they would never leave their land. John Wesley Powell and George W. Ingalls were among the government officials recommending relocation and to insure the success of their proposal advised that no annuities be given except at the designated reservations. Negotiations went on for the removal of the Gosiutes to the Uinta Basin, but the years passed and they remained in Skull Valley. They were absent from official correspondence and forgotten by the government.

Two reservations were eventually established for the Gosiutes on their own lands: in 1912 eighty acres were reserved for their use in Skull Valley with an additional 17,920 acres added in 1919, and in 1914 the Deep Creek Reservation in western Tooele County and eastern Nevada was founded with 34,560 acres.

A young doctor who arrived to practice in the area in 1912 said:

The agent in charge at this time was an old-time bureaucrat who worried more about his reports than about the Indians. In addition to his other duties he was busily trying to make the Gosiutes over into Ohio Presbyterians like the ones he had known back home…. His sister-in-law was supposed to be the schoolteacher, but nary an Indian ever darkened the door of her temple of learning in quest of an education….39

The doctor came to like the Gosiutes and pondered:

Were these Gosiute women wiser than I when they.., let the unfit die? They were good mothers, kind and gentle with their children. Were they also kind in eliminating the weak that the tribe might be perpetuated only by the strong?40

From the tenacious Gosiutes Dr. Joseph H. Peck learned about “psychosomatic medicine ten years before anything about it appeared in medicine journals.” 41 Dr. Peck discovered little about the Indians’ Great Spirit and religion. “Their yearly binges upon marijuana and peote [sic] had somewhat the nature of a religious festival. When questioned about it they always said it was too long and complicated to explain to a white man and we would not understand, a conclusion that was probably true.”42

Dr. Peck practiced medicine in Deep Creek country and Tooele for twenty-seven years before moving away. In 1967, fifty years after first coming to the Gosiute lands, he returned to Deep Creek.

Where there had been nothing but sagebrush and tin cans, now there were green alfalfa fields with plenty of good stock grazing upon them. The wickiups were gone and each little cabin had a radio aerial sticking up out of the roof. I stopped at the first one and asked for some of my old friends. Most of them had gone to the happy hunting grounds…..43

Only three of the sixty-one Skull Valley Gosiutes remain on the reservation. The rest have migrated for school and employment opportunities and live mostly in Tooele and Grantsville. They will soon be dispersed like members of the Shoshone communities that were disbanded after World War II and reside now in northern Utah towns. (Washakie in Box Elder County existed with close ties to the Mormon church until that time.)

The Deep Creek Reservation in 1970 numbered eleven families. Nine women began meeting every Tuesday of that year to make necklaces, bob ties, moccasins, women’s purses, belts, headbands, and earrings. They had to learn beadwork from others; the craft was not part of their tribal skills.”.., they are ?building culture.’ Culture is something the tribe never had.”44 “It went directly from rabbit-skin robes to store-bought clothing.

The ingeniousness of the old Gosiutes is still with them. Men skin the deer, killed on the reservation; and women tan the hides, making lye from charcoal for removing the hair. The women would make more buckskin articles if they had hides. “We don’t have many deer, and our men would have to buy licenses to hunt off the reservation.45

Perhaps these Deep Creek Indians will continue the Gosiute tenacity of refusing to give up their ancestral lands and to improve them with time.

1. John Wesley Powell, Report of J. W. Powell, Exploration of the Colorado River of the West and its Tributaries (Washington, D. C., 1875), p. 42.

2. Lyman Tyler, “The Spaniard and the Ute,” Utah Historical Quarterly 22 (1954): 344?45.

3. The best treatment of this subject is to be found in David J. Weber, The Taos Trappers (Norman, Okla., 1970).

4. The complete interview with Henry Harris, Jr., of the Uintah-Ouray Reservation, is in the collection of the Duke Indian Oral History Project at the University of Utah.

5. Leroy R. Hafen and Ann W. Hafen, The Old Spanish Trail from Santa Fe to Los Angeles (Glendale, Calif., 1954).

6. Floyd A. O’Neil, “A History of the Ute Indians of Utah until 1890” (Ph.D. diss., University of Utah, 1973), p. 50.

7. Jesse D. Jennings, Elmer R. Smith, and Charles E. Dibble, Indians of Utah: Past and Present (Salt Lake City, 1959), p. 100.

8. Ibid., p. 106.

9. Quoted in Ibid., p. 107.

10. Benjamin Davies to Commissioner Dole, June 30, 1861, in Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs (Washington, D. C., 1861), p. 129.

11. Hubert Howe Bancroft, History of Utah (San Francisco, 1890), p. 629.

12. Deseret News, September 25, 1861.

13. Jennings, Smith, and Dibble, Indians of Utah, p. 662.

14. Frank Beckwith, Indian Joe, in Person and in Background [Delta, Utah, 1939], p. 53c. Only seven copies of this unusual monograph were printed privately by Beckwith to send to friends as “my Christmas Greeting Card for 1939.” The Utah State Historical Society’s copy is the gift of J. Cecil Alter.

15. O’Neil, “A History of the Ute Indians of Utah until 1890.”

16. Gregory Coyne Thompson. Southern Ute Lands, 1 848?1 899: The Creation of a Reservation, Occasional Papers of the Center of Southwest Studies, no. I (Durango, Colo., 1975), p. 6. “Dee Brown, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (New York, 1972), p. 367.

17. Dee Brown, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (New York, 1972), p. 367.

18. Marshall Sprague, “The Bloody End of Meeker’s Utopia,” American Heritage 8 (1957): 94.

19. Report of the Ute Commission, 1881,. pp. 33 1?32.

20. Quoted in Robert Enimitt, The Last War Trail (Norman, Okla., 1954), pp. 292?95.

21. U.S., Congress, House, House Report No. 3305, 51st Cong., 2d sess., February 2, 1890, Serial 2885, p. 4.

22. Report of the Secretary of the Interior, 1886, pp. 16-17.

23. Floyd A. O’Neil, “An Anguished Odyssey: The Flight of the Utes, 1906-1908,” Utah Historical Quarterly 36 (1968): 315?27.

24. Beckwith, Indian Joe, p. 61a.

25. William R. Palmer, Pahute Indian Legends (Salt Lake City, 1946), pp. 113-23. The Southern Paiutes Section was written with the help of John R. Alley.

26. Father Escalante’s Journal, 1776-77, ed. Herbert S. Auerbach (Salt Lake City, 1943), pp. 82-83, published as vol. 11 of Utah Historical Quarterly.

27. Thomas J. Farnham, Travels in the Great Western Prairies, 2 vols. (New York, 1973), 2:11.

28. Powell, Exploration of the Colorado, pp. 128-29, 130.

29. U.S., Department of Interior, Bureau of Ethnology, Letters Received 1880, Bureau of American Ethnology Collection, Smithsonian National Anthropology Archives, Washington D. C.

30. Clifford Jake, quoted in Salt Lake Tribune, July 6, 1975.

31. Mark Twain, Roughing It (Hartford, Conn., 1872), pp. 146-47.

32. J. H. Simpson, Explorations Across the Great Basin of the Territory of Utah (Washington, D.C., 1876), p. 36.

33. Ibid., p.56.

34. lbid.

35. See Jennings, Smith, and Dibble, Indians of Utah, pp. 16-19 and 69-85.

36. Carling Malouf and Eisner R. Smith, “Some Gosiute Mythological Characters and Concepts,” Utah Humanities Review 1 (1947): 369-78.

37. See James B. Allen and Ted J. Warner, “The Gosiute Indians in Pioneer Utah,” Utah Historical Quarterly 39 (1971): 162-77.

38. Salt Lake Tribune, May 22, 1960; Earl Spendlove, “The Goshute Revenge,” Golden West 5 (1968-69), pp. 24-27, 50-52.

39. Joseph H. Peck, What Next, Doctor Peck? (Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1959), p. 157.

40. Ibid., p. 170.

41. Ibid p. 165.

42. Ibid., p. 171.

43. Ibid., pp. 207-8.

44. Salt Lake Tribune, April 25, 1970.

45. Ibid.