Newell G. Bringhurst

Utah History Encyclopedia, 1994

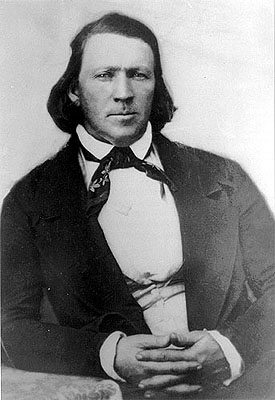

Brigham Young was born June 1, 1801 in Whittingham, Vermont. He was the ninth of eleven children, growing up in an unsettled frontier environment characterized by frequent family moves to various communities throughout upstate New York. Despite the influences of a strict, moralistic family and being exposed to the religious fervor that characterized the “burned-over-district” of upstate New York, he was slow to associate with a particular religious denomination until he formally joined the Methodist Church in 1824. His formal education was minimal and he was apprenticed to be a carpenter, painter, and glazier-trades which he used to support himself. In 1824 he met and married his first wife, Miriam Works, by whom he had two daughters.

By 1830 he was living in Mendon, New York where he first came in contact with the teachings of the newly-formed Mormon church. However, he did not submit to baptism until 14 April 1832 and only then when other members of his immediate family joined. He found Mormonism appealing in its emphasis on Christian primitivism, its millennialistic orientation, authoritarianism, certain Puritan-like beliefs, and the fact that it offered him an avenue to achieve status and recognition through its lay priesthood.

Young’s commitment to Mormonism was further strengthened as a result of his initial meeting with Joseph Smith, whom he found to be a dynamic, charismatic leader and believed to be a true prophet of God. From this point on, Young threw his full energies and talent into promoting Mormonism. In the process he fulfilled several Church missions and other assignments including participation in the Zions’ Camp expedition of 1834. He rose quickly through Church ranks and by 1835 had been appointed to the Council of the Twelve Apostles. In 1838 he took charge of the Mormon exodus to Illinois in the wake of the Church’s expulsion from Missouri. By this time Young was the senior member of the Council of the Twelve.

In 1840 Brigham Young traveled to England, where he took charge of missionary efforts, supervising the dramatic growth of Mormonism in that country. Following his return to Nauvoo in 1841, Young affirmed his complete loyalty to Joseph Smith by embracing the controversial and still-secret practice of polygamy, despite his initial personal reluctance. Young’s commitment was underscored by his eventual marriage to a total of 55 wives (accounts differ) and fathering of fifty-seven children by sixteen of these women.

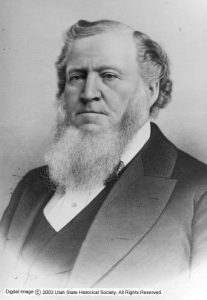

Young emerged as Mormonism’s principal leader, following the assassination of Joseph Smith in 1844, skillfully and successfully beating back the claims of several challengers. By 1846, in response to extreme anti-Mormon violence, Young determined that his followers could not remain in Illinois and proceeded to organize the mass Mormon migration West. Through careful planning and preparation, he presided over what became the largest and best organized westward trek of pioneers in history. He personally led the first pioneer company to the Great Basin, and on 24 July 1847, upon seeing the Great Salt Lake Valley for the first time announced: “It is enough, this is the right place, drive on.” Over the next thirty years, he continued to supervise the migration of thousands of emigrants to the Great Basin through the formation of the Perpetual Emigrating Fund Company, which brought them West by various means, including covered wagon, handcart, church teams and finally railroad. He also oversaw Mormon settlement in dozens of far-flung communities throughout Utah and also in Nevada, Idaho, Wyoming, Arizona, and California in the process becoming one of the foremost colonizers in American history.

With the formation of the territory of Utah in 1850, Young was appointed its first territorial governor, a post which he held until 1857. But relations between Young and the federal government were less than ideal, particularly in wake of the Mormon church’s public acknowledgment of polygamy in 1852. By 1857 relations between Young and the federal government had deteriorated to the point that President James Buchanan dispatched United States Army troops to Utah to ensure the seating of a new territorial governor, resulting in a bloodless skirmish known as the Utah War.

Tensions between Young and federal officials remained high over the next several years, with a variety of actions directed against Young and his followers; these actions included the federal dispatch to Utah of a second armed force in 1862 (this one composed of California Volunteers) and their establishment in Salt Lake City, the enactment of the Morrell Anti-bigamy Act in 1962, and the passage in 1874 of the more severe Poland Act. Young, himself, was subjected to house arrest for several weeks in 1872 and jailed briefly in March 1875.

As a church leader, Brigham Young stood in marked contrast to his predecessor, the charismatic, idealistic, and theologically innovative Joseph Smith. Instead, Young inspired his followers by his down-to-earth demeanor and through his skills as a pragmatic organizer and executive. His emphasis in both his actions and sermons was on the practical means essential for building up the Kingdom of God in a frontier environment. Only rarely did Young venture into the realm of theological and doctrinal innovation and then with mixed results. His pronouncements emphasizing blood atonement and the Adam-God theory had minimal impact on the long-range course of Mormon theological development. More important was Young’s 1847 implementation of denial of the Mormon priesthood to blacks, a practice that remained in effect until its repeal in 1978.

Brigham Young’s activities as a pioneer businessman were also noteworthy. He engaged in a wide variety of enterprises by himself and in partnership with others. In the realm of transportation, these included a wagon express company, a ferryboat company, and a railroad. In the field of manufacturing he processed lumber, wool, sugar beets, iron, and even operated a distillery. His greatest success as a businessman came in real estate. By the time of his death, his personal fortune was calculated at $600,000 making him the most successful Utah businessman up to that time.

Moreover, Young utilized his business talents in an effort to promote Mormon self-sufficiency. He supervised the formation of the Zions Cooperative Mercantile Institution (the basis for the later ZCMI Department Stores) and the establishment of several self-sufficient cooperative communities known as the United Order of Enoch. In undertaking these enterprises, he was seeking to protect and insulate his followers and their distinctive practices (particularly polygamy) from both the actions of an increasingly assertive federal government as well as those of the ever larger number of non-Mormons who had moved into the Great Basin.

However, his efforts were less than successful, particularly in light of larger forces that were bringing the economy of the Great Basin more and more into the mainstream of the larger American economy, a development beyond the control of any one man. Brigham Young died in the midst of such developments on 29 August 1877 of complications resulting from apparent acute appendicitis.

See: Leonard J. Arrington, Brigham Young: American Moses (1985); Newell G. Bringhurst, Brigham Young and the Expanding American Frontier (1986); Dean C. Jessee, ed., Letters of Brigham Young to his Sons (1974); Richard F. Palmer and Karl D. Butler, Brigham Young: The New York Years (1982); Eugene England, Brother Brigham (1980); M. R. Werner, Brigham Young (1925); and Ray B. West, Kingdom of the Saints: The Story of Brigham Young and the Mormons (1957).