Wayne K. Hinton

Utah Historical Quarterly 68 (fall 2000)

At the turn of the nineteenth century, a desire to protect areas of scenic grandeur from the ravages of commercial exploitation and a belief that scenic areas benefited the health and well-being of mankind led to a movement for a United States parks system. In 1900 Congressman John F. Lacey of Iowa introduced legislation to establish an administrative agency known as the National Park Bureau. His bill went nowhere. However, the Antiquities Act passed Congress. This act provided for the preservation of objects of historic or scientific interest that are situated upon lands owned or controlled by the federal government—and it allowed for the creation of national monuments to protect these objects.

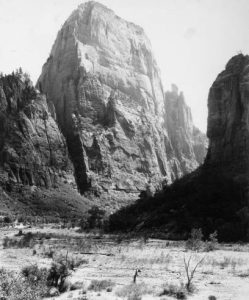

In 1908 eight southern Utah ranchers applied for a survey of lands near Little Zion Canyon in eastern Washington County. The report persuaded President William Howard Taft to set aside on July 31, 1909, some 15,840 acres in Little Zion Canyon as Mukuntuweep National Monument.

The “informal reports” that the agents submitted to the Washington office of the Department of Interior detailed a hard, rough trip getting to the monument. Roadways, culverts, and bridges, such as existed, were only sporadically maintained by Washington County. Even though all who visited the canyon were impressed that “nature seems to have made this canyon a fine gallery of stupendous proportions,” few tourists came. The number of visitors was projected to increase if roads and accommodations became available or were improved.

Partly due to such neglect of the nation’s parks and monuments, in 1910 the American Civic Association, a preservationist organization, pressured Interior Secretary Richard A. Ballinger to again propose the creation of an administrative agency for national parks and monuments. A draft bill, written with major input from members of the American Civic Association, including particularly Frederick Law Olmsted, was drawn up. In 1911 Reed Smoot, Mormon apostle and United States senator from Utah, introduced this Park Bureau bill on Capitol Hill.

When the bill bogged down in Congress, due mainly to opposition from other government agencies, park proponents renamed the proposed park organization the National Park Service. As the bill remained stalled in Congress, railroad officials formed a close alliance with park and preservation advocates. Lobbying by both groups heightened public awareness of the opportunities that parks and monuments provided for marketing America’s scenery. The National Park Service bill passed Congress and was signed by President Woodrow Wilson on August 25, 1916.

Occasional publicity and promotional trips focused some public attention on Mukuntuweep and served to either awaken or enliven the interest of southern Utah residents in the scenic and economic potential of the monument as well as the inadequacies of existing roads. Mormon bishop David Hirschi of Rockville became president of the Five-County Grand Canyon Highway Association, which included Beaver, Iron, Kane, and Washington counties in Utah and Coconino County in Arizona. The first objective was to work for improved roads.

Douglas White of the railroad company helped to organize the Arrowhead Trails Association to develop and promote an automobile route from Los Angeles to Salt Lake City. The activities of the Arrowhead Trails Association brought important results. Road improvements were made and the monument was more accessible to motorists. Another result of the association’s activities was that on September 8, 1916, federal money in the amount of $15,000 was appropriated for a road to extend five miles into Mukuntuweep Canyon.

Despite limitations imposed by America’s entry into World War I in April 1917, the number of visitors at Mukuntuweep grew slightly. Patronage by railroad travelers remained disappointing, and even visitation by motorists was less than expected. Realistically, however, it would take several years of a well-organized publicity campaign for news of the area’s beauty to spread widely.

During the spring of 1917 Douglas White, general passenger agent of the Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad, began an extensive correspondence with Park Service officials to promote development of the Mukuntuweep National Monument.

Albright traveled from the monument to Salt Lake City, where he met with Governor Simon Bamberger. Albright indicated to both the governor and the newspaper reporters that if the state would provide a decent highway connecting the southern border of the monument with the Arrowhead Trails Highway, Congress would maintain a first-class highway within the reserve.

Inspired by his visit, Albright spent time during the winter of 1917–18 reading the Geological Survey reports of southern Utah. This reading convinced him the monument could be and needed to be enlarged beyond its original 15,840 acres to take in other nearby canyons such as Oak Creek and Pine Creek and the high plateaus above, including the Western Rim. At Albright’s urging, Mather prepared a request asking President Wilson to enlarge the monument. By February 1918 Robert Sterling Yard, a railroad officer and a member of the American Civic Association, added to the request by asking that the name of the monument be changed from Mukuntuweep to Zion Canyon National Monument. Albright drew up a proclamation that was signed by Woodrow Wilson on March 18, 1918, enlarging the monument from its original 15,840 acres to 76,800 acres and changing the name to Zion National Monument.

With the enlarged boundary and name change, officials focused their attention on obtaining national park status. The bill proposed to exchange other lands for the school sections, including those whose sales were pending, and to negotiate to buy at fair market value eighty acres of patented private lands within the new boundary. In lieu of its holdings within the park, Utah would be allowed to acquire selected public domain lands outside the boundary.

Congress passed Senator Smoot’s bill establishing Zion National Park; President Woodrow Wilson signed it on November 20, 1919. The annual Conference of National Park Superintendents, held that November in Denver and at Rocky Mountain National Park, was concluding as news arrived of the approval of Zion as a national park.The dedication of Zion as a national park on September 15, 1920, coincided with the conclusion of the National Governor’s Conference held in Salt Lake City. It was hoped that state governors would attend the dedication, be favorably impressed, and share their positive impressions with people in their home states. Several governors did attend. In his enthusiasm for the park, NPS director Stephen Mather returned to Zion regularly; in fact, between 1919 and 1929 he made at least one trip annually. As part of his 1921 visit, he brought Emerson Hough, a Saturday Evening Post writer, and Edmund Heller, a famed naturalist, in the hope that they would share his enthusiasm and help spread the news about Zion’s beauty. While on this trip, Mather’s party traveled to the North Rim of the Grand Canyon, and the director began planning for a tourist circle linking Zion, Bryce, Cedar Breaks, and the North Rim.

Mather believed that if there was ever to be a big park operation at Zion the local people had to understand what a major national park was, and they needed to gain the sophistication necessary for hosting large numbers of visitors.

When Eviend T. Scoyen was appointed the first superintendent of Zion, Mather assured him of the cooperation of the Mormon people and of his own respect for and interest in the people and the country. The director referred to the support that he and the Park Service had received. For instance, since there were no paved roads in Washington County when the park was established, local citizens headed up committees to lobby the State Road Commission for paving.

Jones, a fine photographer, ran a photographic studio in Cedar City. The Union Pacific Company hired him to take his own exquisite collection of slides, which in the days before kodachrome he colored himself, to the East and give slideshows advertising Zion National Park and southern Utah. Jones also worked effectively in cooperation with Mather and others in gaining an agreement among Kane County, Washington County, the state of Utah, and the federal government to bring about construction of the Zion—Mt. Carmel Tunnel and Highway that seemed so important for any future development of tourism at Zion.

Later, when Scoyen was asked to identify the most influential park supporters, he listed Randall Jones as the most important person in southern Utah and called him “the Apostle of the Utah Parks.” He also identified several Mormon leaders: Heber J. Grant, president of the church; Anthony W. Ivins, counselor in the First Presidency; George Albert Smith of the Quorum of Twelve Apostles; and former bishop and current state legislator David Hirschi.

Following the examples of Mather and Albright, Scoyen, despite some initial reticence, developed good relations with local Mormons. His initial apprehension was revealed when a clerk-stenographer position came open. Scoyen asked the Service for a young man who could start at the bottom of a park development program and work up. He cautioned that living conditions near Zion were not on a par with other parks and that southern Utah was “not a very desirable place for a single man, or a man who has a family with children of school age.”

Scoyen also found cooperation in negotiations with local farmers who had holdings within Zion that were needed by the Park Service to consolidate park properties. Those who owned property in the park were generally happy to sell to the government.

In addition to being able to sell properties to the Park Service for a fair market value, there were other benefits that accrued to the local people. The construction of the Zion-Mt. Carmel Tunnel and Highway, which was regarded as essential to tourism development by both local residents and Park Service officials, was begun in 1927 and finished in 1930.

In order to realize its full economic and tourism potential, the park also needed adequate lodge facilities and more effective advertising. During 1923 and 1924 the Union Pacific Company and its subsidiary Utah Parks Company spent $1,713,000 for improvements directly or indirectly related to park development. A thirty-five-mile railroad from Lund to Cedar City was completed in 1923. A modern passenger station cost another $75,000, and the purchase and completion of Hotel El Escalante in Cedar City cost $265,000. A lodge and forty-six cabins were constructed at Zion, and an associated water system. A bus garage in Cedar City and forty eleven-passenger auto-stages bought to convey visitors to Bryce, Cedar Breaks, the North Rim, Pipe Springs, and Zion. National advertising expenses for 1923 to 1924 were $100,000 for ads in the Saturday Evening Post, Literary Digest, and other national magazines, periodicals, and newspapers, and for the publication of an elaborately illustrated booklet on Zion.

Despite the investments, or maybe because of them, Park Service officials increasingly criticized the Union Pacific’s role at Zion. They complained that the railroad looked upon private motorists as pests. Because of its tie to the railroad, the Utah Parks Company advertised only for railroad traffic, and it discriminated in housing accommodations and dining reservations against visitors who came independent of Utah Parks Company bus tours.

In fact, the railroad did not advertise at all in California because ads there would tend to attract only private motorists rather than rail passengers. It seemed impossible to jar railroad officers from their shortsighted attitude and get them to accept the viewpoint that money spent by motorists was as good as that spent by rail passengers. There was hope on the part of Park Service administrators that a “divorce” might sever the Utah Parks Company from any direct relationship to the railroad. This, however, did not happen, and the company continued to concentrate solely on building passenger traffic for the Union Pacific. For Park Service officials there was entirely “too much railroad” in Utah Parks Company management for its own good.

Over the next forty years the association between Park Service and Union Pacific officials deteriorated further. By 1960 the independence afforded to travelers by automobile cut into railroad passenger travel and bus tours significantly. Social and economic changes led the Utah Parks Company in 1969 to begin an attempt to sell their concessioner contract, but Congress would not agree to a sale until 1972.

The number of visits to the park rose from 3,963 in 1920 to 8,400 in 1924, to 21,694 in 1926, and up to 30,916 in 1928. With the completion of the Zion-Mt. Carmel Tunnel and Highway in 1930, visits increased to 55,297. The numbers continued to climb, despite the financial hardships of the Great Depression, to 68,801 in 1934, 124,393 in 1936, and 149,805 in 1938.

In 1915 the 1,000 visitors to Mukuntuweep National Monument found no hotels or public accommodations. The nearest railroad was 102 miles away. In 1941, however, the 190,000 visitors found more than adequate accommodations in the park and at Springdale.

These men, who were so important in the early history of Zion, had developed a genuine fondness for the local people and their cooperative spirit. Horace Albright perhaps said it best: “Cooperation of the local people was cheerfully extended. . . . Orders were issued . . . and were generally obeyed. . . . I shall always remember with keenest delight my early association with those good Mormon people, who, without knowing what a national park was, cooperated so fully. . . .” Indeed, it can be truthfully said that all Americans benefited from the extensive cooperation, if for no other reason than because the scenic wonders of southern Utah seemed to be preserved for future generations.