Jeffrey D. Nichols

History Blazer, September 1995

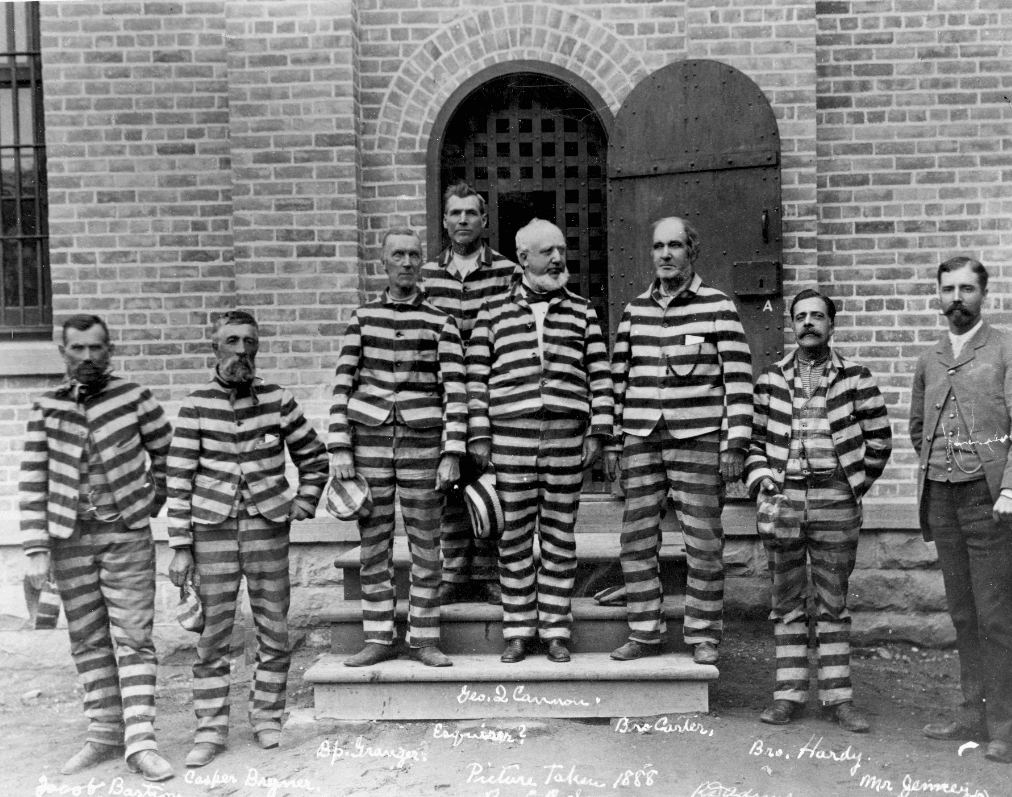

Mormon polygamists in federal penitentiary

The struggle between federal authorities and the LDS church over the issue of polygamy reached its fiercest stage in the late 1880s. A key figure in this controversy was Utah Supreme Court Chief Justice Charles Shuster Zane, during whose tenure hundreds of persons were convicted of illegal cohabitation or polygamy. Zane was a powerful character whose judicial decisions polarized opinions. To radical gentiles and anti-Mormons, he was a hero, although they sometimes felt he did not go far enough in his prosecutions of Mormon “crimes.” To most Mormons, Zane seemed a fanatic bent on destroying thousands of families and the church itself.

Efforts to end polygamy did not begin with Judge Zane. Territorial Governor Stephen S. Harding had told the territorial legislature in December 1862 that the conflict over polygamy was “irrepressible” and warned Mormons not to ignore the antipolygamy legislation that Congress had passed that July. The wholly Mormon legislature responded by denying appropriations for the operation of the district courts, effectively preventing enforcement of the statute.

A series of territorial governors and other federal officials, often of dubious competence and despised as “carpetbaggers,” failed to make much headway in the suppression of plural marriage. Utah Supreme Court Chief Justice James B. McKean, commissioned in 1870, believed that he had a moral duty to fight it. He found, however, that the grand juries impaneled by the responsible local officials—probate court judges, territorial marshals, and attorney generals—refused to return polygamy indictments against their co-religionists. He then attempted to form grand juries impaneled by U. S. marshals, but the legislature refused to pay their expenses, as did Congress. Several indictments returned by McKean’s grand jury were thrown out when the U. S. Supreme Court ruled in the Englebrecht case that the grand jury had been improperly empaneled.

Sen. George Edmunds of Vermont, a leading critic of polygamy, pushed a bill in 1882 that disfranchised polygamists and called for an electoral commission to supervise Utah elections. The Edmunds Act, strengthened by the Edmunds-Tucker Act of 1887 which dissolved the corporation of the LDS church, became the legal tool Zane could use against polygamists.

Justice Charles S. Zane

Charles Zane was the child of New Jersey Quakers but considered himself an agnostic. He moved to Illinois in the 1850s and applied to study law at Abraham Lincoln’s firm but was turned down. After Lincoln’s election as president, however, Zane replaced him as William H. Herndon’s law partner. Zane later partnered with Shelby M. Cullom until he was elected Illinois’ Fifth Circuit judge, a post he filled from 1875 to 1883. In 1884 Zane’s old partner Cullom, now a U. S. senator, convinced Republican President Chester A. Arthur to appoint Zane chief justice of the Utah Supreme Court.

Zane arrived in August 1884 and was assigned to the Third Judicial District (Salt Lake City) as well as his Supreme Court post. He almost immediately established his position on the prosecution of polygamy cases with his sentencing of Rudger Clawson who had been convicted of both polygamy and illegal cohabitation. Clawson’s and Zane’s statements during the sentencing hearing reflect their opposing viewpoints.

Clawson said: “I much regret that the laws of my country should come in conflict with the laws of God, but whenever they do, I shall invariably choose the latter. . . . The constitution . . . expressly states that Congress shall make no law respecting the establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof. . . . The law of 1862 and the Edmunds Bill were expressly designed to operate against marriage, as practiced and believed in by the Latter Day Saints. They are, therefore, unconstitutional, and cannot command the same respect that a constitutional law would.”

Zane’s reply set out his interpretation of the law and the moral and legal issues that he saw in the case: “The constitution of the United States . . . does not protect any person in the practice of polygamy. . . . This belief that polygamy is right, the civilized world recognizes as a mere superstition; it is one of those . . . religious superstitions whose pathway has been lit by the faggot, and red with the blood of innocent people. The American people, through their laws, have pronounced polygamy a crime, and the Court must execute that law. . . .” Zane was ready to offer leniency to any convicted polygamist who pled guilty and renounced the practice, which very few were willing to do. The Deseret News called Zane’s actions part of a “judicial anti-‘Mormon’ crusade.” The News further suggested that a “a specific programme has been decided upon for ulterior purposes, such as the opening of an avenue through which it is hoped that any man in the community, innocent or guilty, can be deprived of his liberty.”

Zane continued his prosecutions, except during July 1888 to May 1889, when the more lenient Elliott Sandford replaced him on the high court. Zane’s return meant the resumption of prosecutions. The Woodruff Manifesto of September 1890 renounced polygamy, and Zane stated that “this alleged revelation I regard as an authoritative expression of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints against the practice of polygamy.” The cases continued exactly as before, however, with the judge offering leniency for those willing to renounce polygamy and harsh sentences of the rest. While some radical anti-Mormons criticized Zane for believing the Manifesto and argued that the real issue was LDS domination of politics and society, he saw his legal duty clearly. When his term ended in 1893 he remained in Utah, convinced that he had performed his job well and that Mormon and gentile could be reconciled now that the LDS church was obeying the law. So far had Zane moved toward moderation, in fact, that he was one of the first three justices elected to the Utah State Supreme Court, serving the short term from 1896 to 1899.

Sources: Thomas G. Alexander, “Charles S. Zane, Apostle of the New Era,” Utah Historical Quarterly 34 (1966); Salt Lake Tribune, November 4, 1884.