The Peoples of Utah, ed. by Helen Z. Papanikolas, © 1976

“Japanese Life in Utah,” pp. 333-62

by Helen Z. Papanikolas and Alice Kasai

The mists rise over

The still pools at Asuka.

Memory does not

Pass away so easily.

…Akahito

For centuries the Japanese were content to live isolated in their wooded land of crags, mists, and ample waters, but the outside world would not allow it. In the early 1600s, fearing the encroaching activities of foreign sea merchants in and about the divine islands, Japan severed commerce with the West and destroyed all seagoing junks to prevent her subjects from traveling abroad. Almost two hundred fifty years later, in 1868, as Japan emerged out of feudalism, Emperor Meiji’s government lifted the restriction to allow about fifty contract laborers to take passage for Hawaii.

This shattering of Japan’s insularity was the result of Commodore Matthew C. Perry’s first incursion, in 1853, into the Bay of Yedo (Tokyo) with four conspicuously armed steamships. In 1859 diplomatic relations began between the United States and Japan; the following year Japanese envoys were sent to Washington.

It was not until the liberalization of Japanese emigration laws in 1885, however, that Japanese were allowed to emigrate to other countries including the United States, where they were explicitly denied any hope for citizenship. A decade earlier the Meiji Restoration had cut off pensions to the disbanded samurai, the exalted warrior caste, leaving large numbers of men without livelihood. Soon afterwards the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 suddenly curtailed the prime source of labor for road and railroad building in the United States. American industrialists took advantage of unrest and unemployment in Japan to insure “cheap” labor for their expansion plans. This accounts for the drastic change in Chinese and Japanese populations in the United States within a twenty-year period: in 1890 there were 107,488 Chinese in the country and 2,039 Japanese; in 1910, 71,531 Chinese and 72,157 Japanese. Fifty-five thousand of the 1910 immigrants had settled in California where long-standing racial hatred against the Chinese was extended to the Japanese and set the pattern for the whole United States.

Since 1885, when the first heavy flow of Japanese migrated to Hawaii, later immigrants had often stopped there before continuing on to the ports of Seattle and San Francisco. From these cities paths fanned out to other western states. One of these immigrants, Joe Toraji Koseki, left his father’s mulberry bushes and silk worms in Fukushima and with an old family spear and samurai sword traveled to Yokohama to board ship for Hawaii. In Yokohama he saw for the first time the ocean–and a “blue-eyed Caucasian–first time I had ever seen a Caucasian. Isn’t that funny…eyes are so big, you know…so big that they were way out?”1

In Honolulu, Hawaii, he joined his brother who was working on a sugar and pineapple plantation. Many of the plantations were owned by white men from the United States and Koseki became accustomed to big-eyed Caucasians. He saw, also for the first time, electricity, telephones, streetcars, and larger steamships than the one that had brought him from Japan. Other Japanese barely landed in Hawaii before they took one of the big steamships for California, but Joe Koseki was to work in a store, volunteer for the United States Army during World War I, cross the ocean to Los Angeles where he did housework, go to San Francisco and back to Los Angeles fleeing the cold weather (he was used to “straw-hat weather”), travel to Chicago and earn a degree in physical therapy from a college of chiropractry, return to Hawaii and leave during the bad times of the Great Depression for Los Angeles where he became a deputy county registrar, be driven to the Turlock, California, assembly center after Pearl Harbor and assigned first to Tule Lake, California, then to the Gila River, Arizona, relocation camps, and find his way to Utah after World War II.

Joe Koseki’s travels were more varied than those of most Japanese immigrants; his American education and occupations were also atypical. Yet Japanese did not fit into the mold of the new immigrants who arrived in the country at the turn of the century.

Unlike the Balkan and Mediterranean immigrants who were almost totally from the poorly educated classes, Japanese aliens included artisans, merchants, students, professionals, and bankers. (The first to come were political refugees who arrived in 1869 and formed the Wakamatsu Silk and Tea Farm Colony in El Dorado County, California.) No matter what classes they came from, the samurai ideals governed their lives.

Japan’s feudal society had been abolished for several decades and samurai were no longer allowed to wear their two swords, the reverent symbols of their caste. The code of feudalism, though, continued: courage and loyalty to one’s people, esteem for stylized politeness, the courteous treatment of inferiors, and exalted respect for elders. Children were taught through the bushido code that they must do nothing that would cause others to laugh at them or bring disgrace upon their families–identical to the principle offilotimo that Greek immigrants cherished. The Japanese carried the hiding of feelings even further, bringing Occidentals to call their controlled expressions inscrutable” and –mysterious.”

Like the Balkan and Mediterranean immigrants, the Japanese intended to return to their fatherlands with money enough to buy land and other property that would raise their status and free them from grasping moneylenders. For many years those destined for the railroads of the American West came from the poorest section of Japan, four southwest prefectures around Hiroshima. Japanese who emigrated from Hawaii were even more impecumous and uneducated. Had it not been for Japanese labor agents who sent ships to bring them to America, a great number of Japanese could not have left their country.

Whatever their background, almost all Japanese began their life in America by working in fields or on railroad section gangs. Until they formed Japanese Associations to protect and aid them, they worked as many hours as they were told, for as little as fifty cents a day, slept in crowded bunkhouses with poor sanitation, and asked only that they be given their native food: rice, fish, Japanese vegetables sprinkled with soy sauce, and tea. Before and after the Gentlemen’s Agreement of 19O7–President Theodore Roosevelt’s diplomatic maneuver that restricted Japanese laborers from coming into the country–educated Japanese were employed as migrant workers in Pacific Coast fields and orchards.

In Utah, Japanese had been working on railroad gangs since the turn of the century. The first Japanese seen by Utahns, however, had been in 1872. The Deseret News of February 7 of that year described a visit of approximately fifty members of Ambassador Extraordinary Iwakura’s party. The visitors were forced to remain a week because of a heavy snowstorm. Territorial Gov. George L. Woods and Mayor Daniel H. Wells headed a public reception for them at City Hall. Members of the state legislature’s judiciary as well as Lt. Col. Henry A. Morrow of Camp Douglas arranged a formal welcome for them.

Ten years after these impressive visitors, the first immigrant Japanese came to Utah. Their arrival began a history called Sanchubuto Nihon Jin (“Intermountain Japanese People”), published on October 30, 1925, by the Japanese-language newspaper Rocky Mountain Times. How these first Japanese left Japan while the emigration prohibition was in force is not known. They were women, brought as prostitutes for Chinese and Caucasian railroad workers. The women had lived respectable lives elsewhere in the United States; but tragedies, often the death of husbands, forced them into prostitution to support themselves and, for some, their children. The newspaper conjectured that the women could also have been shanghaied by brothel owners or their agents. They were contemptuously ostracized.

Increasing numbers of Japanese came into the state during the 1880s to fill jobs on railroad gangs that Chinese had abandoned when riots in Rock Springs and Evanston, Wyoming, and in Carbon County, Utah, mines sent them fleeing to California. Yozo Hashimoto was the earliest Japanese labor agent to supply workers for Intermountain West industries. One of his laborers was a nephew, born in Wakayama Prefecture in 1875, the son of a poor fisherman; he would have had little future in his native country where the eldest son inherited whatever property the father had.2

As soon as he arrived in the United States in 1890 fifteen-year-old Edward Daigoro was sent by his Uncle Yozo to work as a cook on the Great Northern Railroad in Montana. That his nephew knew nothing about cooking had not bothered Yozo. Barely had Daigoro begun learning, however, when vigilantes, riding under the Yellow Peril banner, drove out all Asians and killed many of them. Hiding and running by turns, the men scattered westward.

Edward Daigoro hid in the fields by day and walked by night until he reached Salt Lake City where his uncle had opened a labor agency. In 1902 Daigoro established the E. D. Hashimoto Company at 163 West South Temple in growing Japanese Town. By then he was known as “Daigoro Sama” (“Great Man”) to the Japanese and “E. D.” to American business associates. The Hashimoto Company furnished section gang workers to the Western Pacific and to the Denver and Rio Grande and supplied them with imported Japanese foods, rice, and clothing. Payrolls were sent out through Daigoro; money orders mailed to the men’s families in Japan; credit extended; and numerous legal and governmental forms and applications, difficult for immigrants with limited education to understand, taken care of. Japanese working on labor gangs looked forward to their rare visits to Japanese Town and Hashimoto’s store. By 1904 Daigoro was called Salt Lake City’s Mikado by Americans.

To facilitate placing laborers on railroad gangs, a second Hashimoto agency was opened in Los Angeles just before the San Francisco earthquake of 1906. There Daigoro became friends with A. P. Giannini who had risen from a push-cart peddler of fish to become founder of the Bank of Italy, later known as the Bank of America. Daigoro Hashimoto’s name became well known among American financiers and Japanese immigrants alike. The Japanese were anxious to leave California and Daigoro had no difficulty manning railroad section gangs.

Prejudice against the Japanese increased as more of them arrived in California and worked in fields for Americans until they had saved enough to buy or lease their own land. This thriftiness was called “taking up California’s lands” by the Asiatic Exclusion League and other anti-Japanese organizations. Newspapers inflamed Americans with statements later generally refuted by the report of California’s Special State Investigation of 1909. Besides being called “unhygienic,” “shack dwellers,” not “good” (passive) laborers like the Chinese, under the “complete control of the Mikado,” “clannish,” “unassimilable,” lacking in respect for women by keeping brothels (as if prostitution had been unknown in the country until the Japanese entered it), they were described as incapable of becoming good citizens, when citizenship, the right to which all European immigrants had from the beginnings of the nation, was denied them.

Solemn discussions were held on the extent to which Japanese physical characteristics would be transmitted to interracial offspring, with blatant disregard for the obvious Japanese preference for their own people that excluded even Chinese and other Asians. Yellow Peril was the consuming concern of the day.

With impressive statistics as to yield, acreage, and quality and kinds of crops, the Special State Investigation of 1909 proved conclusively that Japanese were exceptional farmers who could have taught Americans better farming methods. Yet in Sidney Gulick’s The American Japanese Problem, of 1914, a picture has the caption: “This illustrates the stooping work for which Japanese farmers are peculiarly adapted. White men find berry culture exceedingly irksome.”3

Japanese have traditionally held farming in esteem because “it feeds the nation”; just below the samurai class were the farmers. Their special aptitude for farming led to California’s Anti-Alien Land Law of 1914 that prohibited their buying land and restricted their leasing it to three years. Many Japanese became discouraged–it took five years, for example, to establish a grape vineyard–and they left looking for other work.

Setsuzo Uchida, a graduate in economics from the University of Todau in Japan, left his wife Take Yamamoto, who was a rarity, a woman college graduate of Aoyamagakuin College, a Methodist mission school, came to California, and found work picking oranges. His wife arrived in 1914 and with the money Uchida had saved, they rented a farm and raised peas and tomatoes. Prevented from buying the farm, the Uchidas tried fishing to supply canneries in San Pedro and gold mining in Mexico after hearing a Japanese general in the Mexican army speak of the opportunities there. Now eighty-six years old, Mrs. Uchida remembers the young farm laborers:

Yes, some of our workers were Japanese friends, most of them students at the time. As students they came, some of them had a curiosity to do that. But 100 percent farming instinct, farming minds.4

This “farming instinct” that had immediately become apparent to Californians and had led to many farm owners showing them preference when hiring laborers brought another segment of Japanese to Utah. The 1909 Report of the Bureau of Immigration, Labor, and Statistics counted 1,025 Japanese farm workers. The first had come to Utah in 1898 to work on section gangs and had turned to farming at the earliest opportunity. Besides West Coast Japanese looking for land to farm, there were section workers losing their jobs to a deluge of Balkan and Mediterranean immigrants. To help “his boys,” Daigoro Hashimoto established the Clearfield Canning Company and began raising sugar beets for a company later known as the Utah-Idaho Sugar Beet Company. The attraction of farming for the immigrants resulted in Daigoro’s opening a branch sugar-beet center in Delta, Utah.

Japanese farmers settled primarily in Box Elder, Weber, and Salt Lake counties. They were to produce the nationally acclaimed Sweetheart and Jumbo celeries and the Twentieth Century strawberries. The patent on these ever bearing strawberries was held by Taijiro Kasuga and made him a millionaire.

Yet for the first fifteen years of the 1900s, the section gangs were the main source of employment for the Japanese; their foremen remained far longer with the railroads, some of them until Pearl Harbor. Japanese section workers were less welcome than farmers. Section workers were almost always unmarried, and single immigrants brought implications of wantonness to Americans; farmers were usually married, giving a sense of permanence and solidity to their life. The Railroad Notes column in the OgdenStandard of July 26, 1900, quoted Superintendent Young as saying, “A number of Japanese are being employed because contractors can’t depend on white men although they prefer to employ white labor.”

The dependability of the Japanese to withstand the lonely, desolate railroad maintenance work was soon acknowledged by roadmasters, and Daigoro chose from among them men to become foremen over Japanese and other immigrant crews. One of them, Jinzaburo Matsurniya, worked as a section foreman in Jericho near Tintic where two rails converging in the distance, a section house, and a water tank set in the sagebrush were all that could be seen. He remained there until 1917 when he returned to Japan, married, and brought his bride to Jericho. The only people the young bride saw were the railroad men who stopped the freights at the water tank, an occasional Indian, and Mexicans who made up the section crew. During shearing time, Mrs. Matsumiya, now in her late seventies, remembers sheep driven near the section house, and tents and a big shed, for shearing, set up. “It was just a little town.” She recalls, too, the desert in bloom:

…and cactus blooming so pretty…all the little flowers and the cactus are blooming…all over blooming…I thought I’m going to pick…I saw this big dog by the kitchen, a pretty one, too. I said, “Where did that dog came from?” And Grandpa said, “That’s a coyote.”5

In the desert she cared for her children, raised three hundred chickens at a time, ripped the seams of her husband’s clothes to make patterns for new ones that she sewed on a treadle machine, and was one of the shearers herself when the sheep were driven to the water tank. The Matsumiyas ordered their Japanese food from Los Angeles because the freight was cheaper than that from Salt Lake City.

While Jinzaburo Matsumiya lived his lonely life in the 1900s, a Japanese Town was growing in Salt Lake City. Several stores besides Daigoro Hashimoto’s supplied the needs of Utah’s 417 Japanese, and boardinghouses were opened as more immigrants came to work on labor gangs. There were already a few graves in the Japanese section of the city cemetery, including two of infants, buried in 1905, Estella and Oroville Arima. A passerby wonders today if they were children of mixed marriages or simply given Anglo names. They could be the first Nisei born in Utah.

The growth of Japanese population was small but steady. In 1910, 2,110 were counted in the census; in 1920, 2,936. With the increase came more stores and services. The first Japanese Noodle House opened on West Temple in 1907. In the same year the Rocky Mountain Times began a tri-weekly publication and was followed by the Utah Nippo seven years later, which is still being published. In 1912 a Buddhist church was established. Oriental goods stores, restaurants, noodle houses, barbershops, hotels, laundries, dry cleaning stores, fish markets, a tofu bean-cake factory, and produce stands filled the needs of the industrious community.

The newer arrivals continued to be sent by Daigoro Hashimoto to section gangs and to the Utah Fuel Company mines in Sunny-side and other Carbon County coal camps. As Greeks and Italians came by the thousands in the 1900s, learned section-gang work from the Japanese and replaced many of them, more Japanese began going into the mines. Daigoro had contracted with Daniel C. Jackling in 1910 to supply Japanese and Korean laborers for the Bingham Garfield Railroad construction. The Japanese remained to work in the Bingham copper mines as “bank men,” the most hazardous of all labor. Lowering themselves over the banks of the tiers by ropes tied around their waists, the Japanese swung picks into the ore, hundreds of feet above the open-pit chasm. The Japanese were paid more than the Greeks who lived in Greek Town, next to their Jap Town, and with whom they spent paydays gambling. The higher wages of the Japanese was a grievance of the Greeks in the Bingham strike of 1912–a minor one compared to their frustration in trying to force Utah Copper to discharge their own labor agent, Leonidas Skliris. Yet when the Greeks joined the strike called by the Western Federation of Labor, the Japanese followed.

The Greeks, it is said, did not consult them before striking but when the walkout occurred the Orientals took it for granted that work was suspended. Among them is Coney Shihota, said to be the champion wrestler of the camp. He is a powerfully constructed man for his race and has downed many stalwart Greeks. The other Japanese have tacitly appointed him leader.6

The failure of the Bingham strike led to the blacklisting of many union men, including Greeks, the largest segment of miners. Mexicans were recruited to take their places–many of them had come in as strikebreakers–and Daigoro Hashimoto became their labor agent. President Venustiano Carranza met Daigoro and made him honorary Mexican consul in Utah. He was only one of many noted people of Daigoro’s acquaintance that included President William Howard Taft. In 1908 he had married Lois Hide Niiya, a graduate of Kobe College in Japan and the University of California, and built a home for her at 315 South Twelfth East. Many well-known businessmen and politicians of the day were entertained there, and often Gov. William Spry of Utah. Into this center of social life a son, Edward Ichiro (“First Born”) was born February 25, 1911. He remembers as a boy taking apart gold watches brought as gifts by these important visitors and being summarily punished.

Daigoro’s labor agency assured Utah industry of Asians and Mexicans to meet every need and emergency. All mill, smelter, and mining towns had Japanese boardinghouses that camp bosses ran themselves and later, when the Picture Bride Provision of 1910 allowed women to emigrate, with their wives. Daishiro and Kyoichi Sako housed their men in Little Tokyos located in Magna and Garfield.

The Latuda, Carbon County, Japanese camp was managed by Eiji Iwamoto and his wife. They were second cousins whose marriage would have been unthinkable in Japan: Suga, the wife, came from a samurai family; Eiji from farmers. Their mothers were first cousins and arranged the marriage between Eiji, an only son, and Suga to keep the family closely bound. Knowing the marriage would bring derision on their children if they stayed in Japan, they sent them to America.7

In Latuda the samurai daughter awoke at four-thirty in the morning to light a coal stove, prepare breakfast for the boarders, and fill their lunch buckets. Between six and seven the boarders dressed, ate breakfast, and left at seven-thirty with carbide lamps on their heads and lunch buckets in their hands. The eight o’clock mine whistle blew to signal the start of the day shift and again at four o’clock when the men came out of the mine and the afternoon shift began. The Japanese miners returned home, bathed in a large wooden tub in the Iwamoto’s back yard bathhouse (Caucasian miners used the company showers) and ate dinner between five and six. They went to bed early every night except Saturdays when they gambled until dawn. They were enthusiastic card players, and in their bachelor lives Saturday card games were the main diversion.

Whether the Japanese lived in mining towns under “camp bosses” like Eiji Iwamoto or in mill, smelter, or farming areas, neither they nor their children were subjected to continual harassment as were other new immigrant groups. They were derisively called “Japs,” but the explosive antagonisms that the Greeks, Italians, and Slays experienced were seldom directed toward them. There were many reasons for this: the Japanese did not attempt to enter into American social life; they endured slights without retaliation, because of their cultural training in patient acceptance and because they most often thought of themselves as temporary workers in America; of all people they were the most law abiding; and their children, trained under the bushido code, were well behaved, often exceptional students because their home training insisted on diligent studying.

In comparing the Japanese with Greeks in Utah, the former led hard-working, predictable lives. The Greeks were leaders in the Bingham Strike of 1912 and the Carbon County Strike of 1922; the Japanese were followers. Greeks demanded their rights and flaunted public attitudes (hiring American girls in their restaurants and candy stores and being seen with them at movies or in their new cars). Japanese kept within the family and church circles. The Ku Klux Klan campaign of 1924 hardly touched them in Utah, but a new affront came to them that same year. The Japanese Exclusion Act prohibited any Japanese from entering the country and relegated them to the position of the Chinese forty-two years earlier.8 California’s anti-Japanese lobbying had at last been successful. Deprived of citizenship, they were doubly stigmatized as inferior people.

The Japanese coped with the Act as Balkan and Mediterranean immigrants with low quotas did; many of them swam ashore from boats anchored in harbors or were smuggled across the Canadian and Mexican borders by compatriots. The children of the immigrants, the Nisei, were growing older and were becoming aware of this exclusion and restrictions that affected them directly: in larger Utah towns and in Salt Lake City, Asians were barred from the “better white” restaurants and had to sit in the balconies of theatres.

There were stirrings against the Exclusion Act and the earlier Cable Act of 1922 that deprived Nisei women who had married Issei, first generation Japanese, of their citizenship, but as yet the Japanese did not have effective spokesmen. However, an Issei, Henry Y. Kasai, was becoming increasingly active in working with public officials to abolish discrimination in restaurants and in public places, such as swimming pools, but gains were as yet small.

Henry Y. Kasai had come to America with his father and two uncles in 19Q2 at the age of twelve. His father had been a constable and silkworm farmer; his mother had remained in Japan with the younger children. In Mountain View, California, and in Idaho Falls, Idaho, he boarded with American families and learned their language and ways. He then began a fifty-year career in Utah with New York Life Insurance and became well known among businessmen.

The communication most Issei had with the American community was strictly in business: selling produce to wholesale markets and retailing it–their displays of fruit and vegetables were luxuriously artistic; providing laundry, dry-cleaning, and gardening services. Children translated back and forth between their parents and Caucasians. The perpetuation of the Japanese language to insure continued Nisei familiarity in communicating with and for their parents and being proficient in it when lssei and their families returned to Japan, as many believed they would, were the reasons for establishing Japanese schools wherever a sizeable community of immigrants lived. The first school had its inception in Salt Lake City in 1919.

The coldness and indifference outside the Japanese Towns were more than compensated by the richness of life within them. Social activities were concentrated around the churches. Although predominately Buddhist, the Japanese communities included a substantial number of immigrants who had been converted to Christianity in Japan. Following an initial period when Christian missionaries met martyrdom there, a variety of religions were accepted without discrimination. It is not unusual to find Issei who hold membership in two religions.

In 1918 a Japanese Church of Christ was established in Salt Lake City. A Church of Christ church was next established in Ogden and a Buddhist church in Honeyville. A Salt Lake Nichiren Buddhist church had its inception in 1954. Other religious organizations with a small membership are: Church of World Messianity, and Seicho-No-Ie Salt Lake Shinto Soai Kai (“Home of Infinite Life, Wisdom, and Abundance”) with precepts of healing similar to Christian Science. A Mormon Japanese ward is called Dai-Ichi (“Number One”) Branch. Besides these churches, every Christian faith counts Japanese as members. The social functions of each church are attended by nonmember Japanese.

The New Year was, and still is, the most celebrated event of the year. Houses were thoroughly cleaned and the last bath of the year was taken to wash off the “old year’s dirt.” For days in advance festive food was prepared to be eaten during the first week of the year. The golden Tai fish (red sea bream, the “King of Fish”) or Japanese carp was baked whole with eyes wide open, fins and tail spread in a fan shape and the body arched as if it were alive and flipping over ocean waves (shredded white radishes). Mocki (sweet rice pounded into glutinous cakes and topped with tangerines) denoted abundance and was also a symbolic dish. All debts were paid, greeting cards exchanged, and sake (rice wine) drunk.

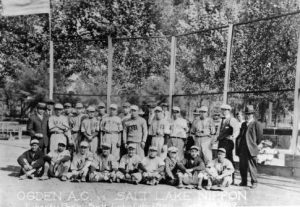

The Salt Lake Nippon baseball team at Liberty Park in 1919

During July, the Obon, comparable to American Memorial Day, was commemorated by Buddhists with prayer services at the church and cemetery. Street dancing was held in the evening. Christmas early began to be celebrated, even by Buddhists, in the traditional American way. Summer picnics gathered Japanese from the entire state in nature’s setting, the love of which they had brought from Japan. Children and adults ran races and played games. Sushis (rice cakes) and nigiri (rice balls) with chicken teriyaki was served, followed by ice cream, soft drinks, and melons. Wrestling contests were the popular attraction, for sumo was Japan’s national sport. Young Issei played baseball and as the Nisei grew up it replaced wrestling.

The first folk dancing yokyo (entertainment) given by the women’s organization Fujinkiai, 1925; musical instruments are samisens.

Fund-raising programs for the Japanese-language schools were much-anticipated events, with practising of songs, dances, and singing of poetry (shigin). Instruments used were the samisen (a three-stringed, banjo-like instrument with long neck), the shakuachi (bamboo flute), and the okoto (horizontal harp that is placed on the floor). In Salt Lake City and in Ogden, kabuki dramas were performed with wigs, stylized makeup, and elaborate costumes of the old feudal era. Japanese movies were regularly shown, and occasionally performers from Japan stopped on tour to entertain.

Until the Second World War, the Issei, ineligible for citizenship, observed the emperor’s birthday and Japan’s Foundation Day. On Girls’ and Boys’ Festival Days, family doll sets were used to teach girls the significance of tea ceremony and flower arrangement–“to promote good breeding”; boys were told to be courageous and to surmount obstacles as signified by a paper carp that was flown over each house that had a son. Reverence for education, obedience and respect for parents and elders, loyalty to one’s family, friends, and country were all part of the children’s training. “I think,” Toraji Koseki said, “it comes from the samurai way of life, and children–obey…just comes natural.”

Children’s obedience to parents included their submission in marriage arrangements. Neither attraction nor personal feeling was taken into account. Each marriage had abaishakunin, a “go-between.” The baishakunin decided who were the best mates for the children, counseled them, and remained as godparents to the family. This role terminated with the Sansei (third generation), but most of the Nisei followed the tradition. When the 1924 Exclusion Act prohibited brides coming from Japan, many Issei men waited around for the first Nisei girls to become of marriageable age, resulting in big age differences between the couples.

Until the depression years of the 1930s, the Japanese Towns expanded with more immigrants and Nisei children, but the economic decline cut off jobs first among nonwhites. During the decade, 1,059 Japanese left the state. Many moved to California and sought help from countrymen who had come from the same ken or prefecture in Japan. Others returned with their savings to Japan where the cost of living was lower.

There were two important legislative acts of these years, both passed in 1931, the result of lobbying by a young organization, the Japanese American Citizens League. The 1922 Cable Act was amended, regaining American citizenship for Nisei women who had married Issei men; and American citizenship was granted to 700 World War I veterans. In Utah, legislation in 1937 reduced license fees for Issei from twelve dollars to three, the same as for citizens. The gains had increased. Near the end of the decade, Mike Masaru Masaoka, a brilliant young Salt Lake City Nisei Mormon and instructor in the University of Utah speech department, overcame misgivings and involved himself in the JACL. He became the extremely effective spokesman that Japanese needed during and after World War II. He was encouraged and helped by a former teacher at the University of Utah, who had served a Latter-day Saints’ mission to Japan in his youth, United States Sen. Elbert D. Thomas.

Japanese in the United States were stunned by the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The traumatic mass movement of the Japanese from the West Coast began.9 Under the infamous Executive Order 9066, the army was empowered to oversee the “enemy alien problem.” Houses, shops, and property of the deportees were sold for a fraction of the cost or abandoned. Decades, even generations, of hard work were swept away with the arrival of the United States soldiers.

In Utah, as elsewhere in the United States, reactions to the Japanese varied from threats to bewilderment. Japanese and people who had known and worked with them were uneasy at facing each other. Dr. Edward Ichiro (“First Born”) Hashimoto, son of the Mikado, entered his gross anatomy class at the University of Utah Medical School, where he was to teach for forty years, to a profound silence. “What are you fellows staring at?” he said. “I’m Irish. I was home in Dublin at the time !” With relief and delight, Dr. Hashimoto’s students relaxed. Known for being able to draw human figures with both hands simultaneously, the doctor was called, from then on, the “Ambidextrous Irishman.”

Dr. Hashimoto’s father had died at age sixty-one, five years before Pearl Harbor. He had added significant accomplishments to his name: helped establish Tracy Bank and Trust Company; held a franchise from National Baldwin for the Asian distribution of radio earphones; drilled one of the first oil wells in Casper, Wyoming; organized the Red Feather Stages in 1926 (a subsidiary of the present Greyhound Bus Lines); was involved in gold and silver mines in Guerrero, Mexico; opened a mine near Salmon, Idaho; and was an organizer of the Mountain City Copper Mine in Nevada. Had he lived, his leadership and achievements would have had to be ignored under American policy for interning noted Japanese.

Ten relocation camps were hastily built to house a hundred ten thousand Japanese Americans. Neither German nor Italian nationals were subjected to this kind of treatment. The evacuation was under the direction of Gen. John L. De Witt, commander of the Western Defense Command. His derogatory pronouncement “A Jap’s a Jap” and his curfew orders from 8:00 P.M. to 6:00 A.M. still rankle in the memory of Japanese Americans and their sympathizers.

The Japanese were given as little as six days to dispose of their property and be ready for evacuation. There was pandemonium, with certain areas interpreting army orders more strictly than others. Initially the evacuation was to be voluntary; the Japanese were to find inland locations to settle themselves. Men left their families and traveled to the Mountain States hoping for help from relatives and friends. Fearful of what could happen to their families in their absence, of the possibility of mob action as they drove on, of the signs in Idaho, Utah, and Colorado, “No Japs Wanted Here,” they slept in their cars and ate cold food at the side of the road. The voluntary program was a failure; the inland Japanese were overwhelmed by public hostility, loss of jobs, and the internment of their leading members.

One “successful” voluntary evacuee, Frank Endo, who owned the Yamato Grocery Store in Oakland, California, came with a brother-in-law to Salt Lake City to solicit help from his friends, the Ikuzo Tsuyukis, owners of the U. S. Cafe. There were many men like him in the city searching and not finding assistance. Frank Endo met Fred Wada, a former Utahn who was negotiating with Sheriff George A. Fisher of Keetley, Wasatch County, to lease 3,909 acres of sagebrush land. Endo asked to bring his family of twelve brothers and sisters, their families, including parents-in-law, to join the colony. Hurrying back to his family, he disposed of as much of his store goods as was possible. Caucasians rushed to buy it at half cost; some of it was taken back by wholesale houses at a loss to the Endos, but Japanese food had no market.

The Endos loaded all staples and nonperishables into a Union Pacific railroad car and sent it on to Keetley to help feed the Endo clan. The families drove their cars from Oakland to Utah. When the Frank Endos reached Sandy, they stopped at a cafe. A sign in the cafe window read “No Dogs, No Japs.” Two of Frank Endo’s brothers were already in the United States Army; two younger brothers, one of whom would die in the Korean War, sat in the crowded car. “I wonder,” one of them said, “when I’m old enough to be drafted, what they would do if I walked in wearing my army uniform.”10

Under Fred Wada’s leadership, the families, part of a ninety-member colony, cleared the land of sagebrush, tilled the valley and mountainsides, cultivated the soil, and raised “victory food.” They lived in a motel next to a building used as a meetinghouse and office. One night a bomb was thrown against the building and demolished it, but no one was inside at the time. The Deseret News used a half-page to denounce the bombing.

Joe Toraji Koseki, who had seen his first blue-eyed Caucasian in Yokohama, was on National Guard maneuvers in Hawaii when Pearl Harbor was bombed. An American Legionnaire, Commodore Perry Post, he was forced to resign from the National Guard and board an evacuation ship for California. There the evacuees were read the prohibition against their keeping arms, cameras, and radios. Koseki gave his ancient spear and samurai sword to a Pasadena high school principal whom he had heard collected Japanese arms. Other Japanese buried their samurai swords in their back yards hoping to return to dig them up.

The Matsumiyas were visited by the roadmaster in their Jericho section house and told to leave within three days. Railroads and mines had been classified war industries and closed to Japanese. After thirty-five years of section work, Matsumiya went from one farm to another in the Payson area looking for work. Years of uprooted life followed with Matsumiya thinning and hoeing beets, his wife sewing for Caucasians for as little as ten cents an hour, then moving to Salt Lake City where Mr. Matsumiya did janitor work for the Mayflower Restaurant, the kitchen of which was completely staffed with Japanese, and Mrs. Matsumiya altered suits for Hibbs Clothing store. Their daughters went to school and did housework for Caucasians; a son was in Alabama learning to “chicksex,” a popular vocation for Japanese.

Mrs. Uchida, the Methodist college graduate, and her husband were living in Idaho Falls at the time of Pearl Harbor. Her husband was secretary of the Japanese Association there and she taught Japanese school. (Until World War II, many Japanese still expected to return to Japan and often took the ashes of their dead to be buried there.) On December 8 the Federal Bureau of Investigation sent the local sheriff to take them into custody. Orders were given to remove all-important Issei to internment camps “to leave the Japanese leaderless.” Uchida was sent to camps in North Dakota and Louisiana and his wife to Missoula, Montana, Seattle, Washington, and then to Seagoville, Texas, where she was placed in charge of Japanese women and children from California, Peru, and the Panama Canal Zone.

Another leader interned was Henry Kasai, the insurance agent who had begun the fight against discrimination in the twenties. He had married a Nisei, many years his junior, Alice Iwamoto, daughter of the Latuda mine camp boss. Kasai was in Teton, Idaho, the day of Pearl Harbor at a wedding celebration. He had effected a conciliation between the parents of the bride and groom who had objected to the marriage because it would unite farmers with etas, the lowest in the Confucian hierarchy. The etas were animal slaughterers and hide tanners; they were from northern Japan, often blue-eyed, from a Caucasian strain, believed to be Russian.

During the wedding feast, the sheriff of Rexburg, on orders from the FBI, came to the house and took Henry Kasai to jail. He was sent to Missoula and Livingston, Montana, and then to Albuquerque, New Mexico. His wife and children remained in Salt Lake City and lived by taking in boarders and withdrawing $150 a month from their savings account, the maximum allowed families of internees. His mother-in-law, daughter of the samurai, was shocked into illness and asked that her ashes be buried in Japan with her family’s. Two months later she died.

Tomoko Watanuki Yano, daughter of a community leader, said:

My father not only lost his job and seniority rights but the dignity and honor of a proud man. He was employed by the Tooele smelter as a camp boss. As a bilinguist, he also taught Japanese language classes. Since father was taken away so abruptly, mother was left without any means of support. She was ordered to leave her home…with no place to go. Within a week, my mother was destitute, homeless, scorned and shunned by her community friends–after living there for twenty years. No one would rent them a house, so they accepted the offer of another Japanese family to use their upstairs storage space. There, my mother, sister, brother and his family, and three elderly Issei men from camp lived from day to day in very confined quarters under most inconvenient conditions.

When my younger brother was inducted into the service, my father was abruptly released after two years confinement. He came back a thoroughly dispirited and beaten person…He had never been sick a day in his life, but in camp he contracted a lung disease and died in 1948 of cancer. Over the years, this injustice has rankled and festered my conscience every time I see my eighty-three-year-old mother and realize more fully what she had to endure.

The stories of the Endos, Kosekis, Matsumiyas, Uchidas, Watanukis, and Kasais can be echoed a hundred thousand times. Stranded, desolate, in panic, they needed the conscience of the nation to arise in their defense. Sporadic, weak defenses did come from a few individuals, hut it was left to Mike Masaoka and the Japanese American Citizens League to fight a tidal wave of irrational, anti-Japanese hysteria. Feverishly working to help the Japanese evacuees, Masaoka was jailed in North Platte, Nebraska, and held incommunicado for two days. He was then allowed to make a telephone call but warned not to say he was in jail. “I’m stuck here in North Platte, Nebraska,” he told a colleague. “I’m at the, ah, the Palace Hotel.” A return call to the Palace Hotel revealed where Masaoka really was and a telephone appeal to Sen. Elbert D. Thomas effected his release. Masaoka boarded a train west only to be taken off at Cheyenne, Wyoming, when local police officers walked through and arrested him because he was an Asian. Again Senator Thomas intervened and Masaoka continued west to the Japanese in their great crisis.11

Eight thousand evacuees were sent to the Central Utah War Relocation Center that came to be called Topaz after the nearby mountains. The cold, drafty barracks were built on nearly twenty thousand acres of arid land at a cost of five million dollars. Another five million was spent yearly for upkeep. A young evacuee said of Topaz: “Topaz looked so big, so enormous to us. It made me feel like an ant. Every place we go we can not escape the dust–dust and more dust, dust everywhere–I wonder who found this desert and why they put us in a place like this?”12

The fine silt dust demoralized them all. Mine Okubo said on glimpsing Topaz, “the Jewel of the Desert” as it was sardonically called:

–suddenly, the Central Utah Relocation Project was stretched out before us in a cloud of dust. It was a desolate scene. Hundreds of low black barracks covered with tarred paper were lined up row after row. A few telephone poles stood like sentinels and soldiers could be seen patrolling the grounds. The bus struggled through the soft alkaline dirt–when we finally battled our way into the safety of the building we looked as if we had fallen into a flour barrel.13

In nominating Topaz for the State Register of Historic Sites over thirty years later, LaVell Johnson, long-time resident and historian of Millard County, said, “We were afraid of the Japanese in the camp. I don’t know why. It seems strange now that we were.

In the three years of its existence, only one incident of violence occurred at Topaz. An elderly man wandered toward the off-limits, outer barbed-wire fence in search of rocks and was shot by the sentry. The entire camp attended his funeral and a delegation angrily protested to camp officials. Several young men became enraged and were sent to the camp at Tule Lake, California, where security was tighter.

Three thousand students were enrolled in the Topaz school system and taught by both Japanese and American teachers. They were taken on field trips to hunt fossils, arrowheads, and topaz crystals. The Topaz Times was published by the evacuees; art classes were held, using sagebrush and other desert materials to create art forms for their barren quarters. The people behind barbed wire made valiant efforts to make adjustment easier for their children, but it was a time of bitterness and loss. The following haiku was composed by Miyuki Aoyama while in the Heart Mountain, Wyoming, camp:

Snow upon the rooftop,

Snow upon the coal;

Winter in Wyoming? Winter in my soul.14

Until 1946 the evacuees endured Topaz while Japanese elsewhere in the state had comparative freedom but suffered continued oppression. After the FBI unsuccessfully searched “enemy aliens” for everything from dynamite to invisible ink, they kept the Japanese under close watch. Veterans groups were vociferous in condemning Issei and Nisei alike. President Elmer G. Peterson of Utah State University refused admittance of Nisei students. The Utah Fish and Game Commission denied fishing licenses to the Japanese. State Sen. Ira A. Huggins sponsored a bill that became law allowing aliens to lease land only on a renewable, yearly contract. Union miners effectively stopped the hiring of evacuees at Bingham. Business licenses were denied throughout the state. In Orem a large group of white youths attacked five young Nisei, part of the labor force of Japanese brought in to harvest the fruit crop.15

Japanese rallied to help each other, and influential Utahns aided them in many ways. When the national headquarters of the Japanese American Citizens League and the Buddhist church were temporarily moved to Salt Lake City, Mayor Ab Jenkins waited at the state border to welcome caravans from San Francisco and escort them into the capital. Former Gov. Henry Blood, Gov. Herbert B. Maw, Sen. Elbert D. Thomas, and Claude T. Barnes, prominent attorney, gave assistance and quelled irrational demands, such as outcries to cut down the Japanese cherry trees on the State Capitol grounds.

The Japanese-American Relocation Aid Committee collected contributions and raised several thousand dollars for books and recreational equipment for the school children in Topaz. A Nisei Victory Committee was organized for the USO (United Services Organization). The Nisei army volunteers from the ten relocation centers were all trained and processed at Fort Douglas, in Salt Lake City. With headquarters at the YWCA, one of the few places still open to Japanese, the Victory Committee sponsored socials, sent packages to soldiers, and made visits to Bushnell Hospital in Brigham City where Nisei solders were recuperating from injuries suffered in Italy and France. (The Nisei 442d Regimental Combat Team was the most highly decorated regiment during the war.) Eighteen names of war dead from Utah are engraved on the Nisei War Monument in the Salt Lake City Cemetery.

At war’s end the Japanese dispersed throughout the United States. Little Tokyos and Japanese Towns were not rebuilt, and assimilation became swift. Many evacuees remained in Utah; the 1950 Census reported an increase of 1,183 Japanese in the state. Fred Wada, head of the Keetley farm colony, returned to Los Angeles and became a member of the Harbor Commission. The Frank Endos, also with the colony, remained in Salt Lake City and opened a dry-cleaning establishment. The Uchidas settled in Ogden; Joe Toraji Koseki made Salt Lake City his permanent residence and did not again see his samurai sword; and the Matsumiyas never returned to their section house in Jericho. Twelve years afterwards, Eiji Iwamoto, who had become blind in 1935 while working as camp boss, returned to Japan with his wife’s ashes and stayed there to die.

After the war the JACL held its first convention since 1941 in Denver. At this 1946 meeting the members resolved to gain citizenship for the Issei and to ask indemnity for evacuation losses. Mike Masaoka was sent to lobby for these causes and, according to the Readers’ Digest, became “Washington’s Most Successful Lobbyist.” The Evacuation Indemnity Claims Act passed in 1948 provided payment of one-tenth of the evacuees’ property losses. The total loss was estimated at $400 million; $38 million was paid to 26,560 claimants.

A year earlier in Utah the alien land law was repealed; two years later, in 1949, Issei were granted hunting licenses. In 1951 the armed forces recognized Buddhism as a major religion and the following year the Walter-McCarran Immigration and Naturalization Act granted Issei citizenship. In 1963 Utah repealed its anti-miscegenation law that had caused tragic problems with racially mixed marriages unrecognized in the state, the number greatly increased by soldiers returning with Asian brides. Two years later Utah passed fair employment and public accommodation measures that included validation retroactively of racially mixed marriages. In 1968 new quotas for immigrants were fixed: 170,000 for the Eastern Hemisphere and 120,000 for the Western Hemisphere. In 1970 Title II of the Internal Security Act of 1950 was repealed, withdrawing federal authority for arbitrary prevention, detention, and concentration camp internment.

Two events of the forties presaged these changes in attitude toward the Japanese in Utah. Wat Misaka of Ogden became the first Nisei member of a University of Utah varsity basketball team. He was one of the “Cinderella Kids” from Utah who won the National Invitational Tournament in 1944–now a mechanical engineer and active civic worker. In 1947 George Shibata of Garland became the first Nisei appointed to West Point through the sponsorship of Sen. Elbert D. Thomas. He received his commission in the Air Force in 1951.

Utah Nisei are among the leaders in Japanese-American affairs. Mike Masaoka won the 1950 Nisei of the Biennium, JACL Award for distinguished leadership. Henry Y. Kasai was the JACL recipient in 1964, and ten years later Raymond S. Uno, Salt Lake City attorney, was similarly honored.

Although the population of Utahns with Japanese ancestry was estimated at only forty-seven hundred in 1970, a high percentage have advanced college degrees: doctors, dentists, lawyers, architects, educators, engineers, and social workers. When feudalism was abolished in Japan, not family status but personal ability and achievement judged a person. Education became a goal of first magnitude and parents and children led hard-working, Spartan lives to accomplish this aim. “I will be glad to eat only one meal a day to support you through medical school,” an Issei told his son.16

A considerable number of Utah Nisei with graduate school degrees work for the disadvantaged. Architect Carl Inoway is director of Assist (non-profit community planning organization); Jimi Mitsunaga is founder and chairman of Legal Defenders; many others work in mental health and social work programs.

Nisei are also entering politics. Yukus Inouye of American Fork serves as Utah County commissioner, and other contestants have shown strength at the polls. The third generation Sansei with greater verbal skills and less passivity are expected to become increasingly active in politics.

Another outstanding contribution of the Japanese is in cultural and aesthetic values. Mrs. Izyo Kiyoshi Sauki, whose professional title is Madame Ogyoku, has given many years’ dedication to the annual Salt Lake Tribune Flower Show. Her students participate in larger numbers each year with unusual exhibits that show through the art of flower arrangement the balanced relationship of man, earth, and heaven.

The Japanese community worked with Mrs. Otto Weisley of the Salt Lake Council of Women to fulfill her life’s goal of an International Peace Garden in Jordan Park. The Japanese section was the first completed, at the farthest end of the garden. Not only the Japanese in Utah but those of the Intermountain area contributed to the project. Friends in Japan sent stone lanterns, a bronze statue of the Goddess of Peace, a teahouse, and a gateway. Annually the Japanese-American gardeners, always in demand for their special talent, aid the city parks’ employees by pruning, shaping, and weeding the Peace Garden.

Each year the public anticipates the Obon and Asian Festivals. The Buddhist church still observes its Memorial Day with a street celebration: music, lanterns, and Obon dancing with participants dressed in bright kimonos. The Japanese Church of Christ presents a program that includes exhibits, dancing, singing, food, and games.

The Judo Clubs in Salt Lake City and Ogden have trained many boys and girls in self-defense and each November are hosts for the Intermountain Tournament.

Honors to the Japanese of Utah have also come from Japan whose people had once looked down on immigrants to this country. Through the office of the prime minister, recognitions have been bestowed on septuagenarian Issei for their contributions in improving relations between their mother country and their adopted land.

In 1965 Henry Y. Kasai was decorated with the Order of the Sacred Treasure Fifth Class for his work in cultivating understanding between Caucasians and Japanese-Americans in Utah. He also received, posthumously, the American Phi Delta Kappa “Man of the Year” award for distinguished work in international education.

In 1968 Mrs. Kuniko Terasawa, publisher of the Utah Nippo, also received the Order of the Sacred Treasure Fifth Class for her efforts through the press to help the Japanese people of Utah in many ways, including counseling in domestic problems.

In 1969 Mrs. Take Uchida was given the Order of the Sacred Treasure Sixth Class for her work in teaching English to Issei and Japanese to Nisei and for community leadership.

In 1968 Mike M. Masaoka received the highest honor that Japan bestows on a foreigner in a special ceremony held in Tokyo. Premier Eisaku Sato presented him with the Order of the Rising Sun Third Class.

In 1960 Japan and the United States celebrated the centennial year of the treaty that opened diplomatic relations between the two countries. Further significance was given the event in Utah by the silver anniversary of the Salt Lake Chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League with their only Issei president, Henry Y. Kasai, in attendance.

Today increasing intermarriage and assimilation are rapidly changing Japanese-American communities. The Sansei have freed themselves from many restrictions of the samurai code, particularly submissiveness to elders and full and rigid responsibility for their standing in life–sources of conflict for their Nisei parents. Their assimilation has been easier than that of their parents: they were not bound to truck farming and to stoop labor as their parents and grandparents were, and their parents had achieved middle-class status during the Sansei’s growing years. Not many knew the debasement and bitterness of internment and other extreme forms of discrimination. Few attend Japanese schools and most do not speak the language of their grandparents. When marriages take place among Sansei, there is no thought given to classes: samurai, farming, merchant, or eta.

In 1966 Japanese Town was demolished and the Salt Palace convention center built in its place. The Buddhist and Japanese Christian churches on the block west of it are all that exist of the old Japanese area. They stand as proud reminders of a Japanese immigrant life that laid the foundation for the economic and cultural enrichment of succeeding generations and added a unique quality to Utah’s history.

Source materials used in this essay for the historical and cultural background of Issei (first-generation Japanese) and Nisei (second-generation Japanese) are: Orientals and Their Cultural Adjustment, Social Science Source Documents, no. 4, Fisk University (Nashville, Tenn., 1946); Edwin 0. Reischauer and John K. Fairbank, East Asia: The Great Tradition(Boston, 1958) Ruth Benedict, The Chrysanthemum and the Sword: Patterns in Japanese Culture (Boston, 1946) ; Bill Hosokawa, Nisei: The Quiet Americans (New York, 1969); Hisa Aoki, “Functional Analysis of Mono-Racial In-Groups: Nisci Congeniality Primary Groups on the University of Utah Campus” (MA. thesis, University of Utah, 1950) ; Steven Kiyoshi Abe, “Nisei Personality Characteristics as Measured by the Edwards Personal Preference Schedule and Minnesota Multiphase Personality Inventory” (M.A. thesis, University of Utah, 1958); Isan Horinouchi, “Educational Values and Preadaptation in the Acculturation of Japanese Americans,” Sacramento Anthropological Society, paper 7, (Sacramento, Calif., 1967) ; Alice Kasai, “History of the Japanese in Utah,” typescript, Asian Studies Center, University of Utah; Leonard J. Arrington, The Price of Prejudice (Logan, Utah, 1962); Elmer R. Smith, “The Japanese’ in Utah,” Utah Humanities Review 2(1948).

1 Tape-recorded interview with Joe Toraji Koseki, American West Center, University of Utah.

2 Tricia Corbett, “The Ambidextrous Irishman,” Utah Medical Bulletin, January 1973, pp. 3-6; interviews with Dr. Edward I. Hashimoto, April 12 and 16, 1975; and typescript by Dr. Hashimoto were used for biographical details of Edward Daigoro Hashimoto’s life.

3 See Sidney L. Gulick, The American Japanese Problem (New York, 1914) for California’s anti-Japanese response.

4 Tape-recorded interview with Mrs. Take Uchida, American West Center.

5 Tape-recorded interview with Mrs. Chiyo Matsumiya, American West Center.

6 Helen Zeese Papanikolas, “Life and Labor among the Immigrants of Bingham Canyon,” Utah Historical Quarterly 33 (1965): 295.

7 Alice Kasai, “My Family,” typescript in authors’ possession.

8 See Julia E. Johnsen, Japanese Exclusion (New York, 1925).

9 See Hosokawa, Nisei, for the internment and relocation epoch and Mike Masura Masaoka’s work during this period.

10 Interview with Mr. and Mrs. Frank Endo, March 13, 1975.

11 Hosokawa, Nisei, p. 227.

12 Maisie Conrat and Richard Conrat, Executive Order 9066: The Internment of 110,000 Japanese Americans (Los Angeles, 1972), p. 73.

13 Hosokawa, Nisei, p. 344.

14 Ibid., p. 337.

15 Michael Ross Strode, The Salt Lake Tribune Account of Utah’s Discrimination Against the Japanese Americans, 1942-1944,” typescript, Asian Studies Center, University of Utah.

16 Horinouchi, “Educational Values and Preadaptation in the Acculturation of Japanese Americans,” p. 41.