Philip F. Notarianni

“The Mansion, Mining, and Snow”

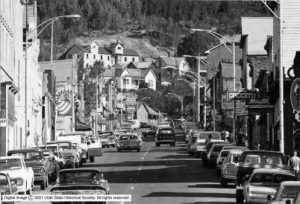

Park City, 1974

Mining and skiing loom as significant factors in the economic growth and development of Utah. Mining, in tandem with the railroad industry, carried Utah from an agrarian economy to one more industrialized and diversified. In the many mining towns, service industries thrived, while Utah’s population became more culturally diverse. Skiing, and the world of winter sports recreation, created both a new direction and extension of life for various mining areas in the state. In both cases, these activities share a common origin—the magnificent, snow-covered mountains of the Beehive State.

Park City rises as among the state’s highest producers of mineral wealth. Such earth wielded power and influence, and opportunity. Rags to riches stories abound in mining lore. Thomas Kearns rose from mucker (a laborer shoveling ore deep underground) to millionaire, epitomizing the dream of every prospector. The Silver King Mine, in Park City, owned in part by Kearns, provided this Canadian of Irish descent with incredible resources. At the turn of the twentieth century, many of these mining entrepreneurs changed the image of Salt Lake City by constructing fabulous mansions on Brigham Street (South Temple). The economic resources derived from mining provided an impetus for growth in both Salt Lake City and Utah. In the historical record, Thomas Kearns, mining, and Park City remain synonymous, as does the Kearns Mansion.

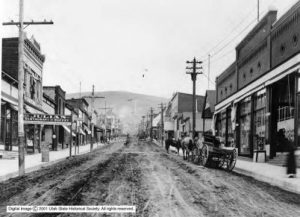

Park City, 1912

Numerous sources chronicled the construction of the Mansion, designed by prominent architect Carl M. Neuhausen. The Salt Lake Tribune declared in 1899, “Stately Silver King Mansion to be Erected on Brigham Street at the Head of Sixth East.”1 Work commenced in 1900. On 31 December 1901, the Tribune ran an article on the “Artistic and Palatial Home,” providing readers with an in-depth peek into the Mansion’s rooms and furnishings. However, the article mentioned specifically that the residence was, “now nearly completed.”2

Senator Thomas and Jennie Judge Kearns hosted a gala social event in opening their home to friends and invited guests in November 1902—the year the Mansion was officially completed. Kearns’ friends in Park City received a special invitation, as the Park Record noted: “The Record acknowledged receipt of an invitation to attend the house warming on Tuesday and Wednesday next to be given by Senator and Mrs. Thomas Kearns in honor of the completion of their palatial home in Salt Lake.”3 The Salt Lake Tribune called the occasion a “Bright Social Event,” affirming that “Senator and Mrs. Thomas Kearns opened their new home to a number of their friends last evening, with the result that Salt Lake society enjoyed one of the most brilliant receptions in its history.”4 Thus, the Kearns Mansion, financed largely by income derived from Park City mining, assumed its special place on the east end of South Temple.

“The Park” thrived as a silver-rich area in western Summit County. Tucked in the mountains, Park City, with its winding roads navigating steep and narrow mountain terrain, stood in marked contrast to agricultural villages laid out like checkerboards. Here, weather and the elements dictated the game. In such an area, miners and their families learned to deal with winter weather, and often used it to advantage. Additionally, mining attracted a diverse labor force—with miners immigrating from northern European countries, such as Finland and Sweden. These people lived in snowy regions, and for centuries learned to adapt and thrive in those climatic conditions. Finding ways to travel in snow formed part of their cultural traditions.

Early in Park City’s history, mines transported ore and materials in the winter by use of a sleigh. Several examples from the Park Record, 1897, illustrate the point.

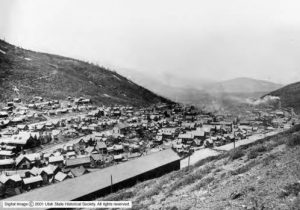

Park City, 1896

The Daly-west resumed ore hauling to the sampler the early part of the week but the teams had to be taken off again owing to poor sleighing.5

The sleighing is fairly good, and in consequence the Daly West is again one of the Park’s regular shippers.6

The recent fall of snow, followed by the present cold snap, has resulted in making the sleighing to the various mines the best so far this season. In consequence a decided increase in ore shipments will be noted from now on.7

The sleigh proved to be a reliable mode of transporting almost anything in snowy weather. Historic photographs show wagons converted into sleighs moving people and material on Park City’s Main Street.

Even in 1902, Park City residents rejoiced in snow. “It was a beautiful snow storm, and our residents in general, and the teamsters in particular, rejoiceth, for it means good sleighing for many weeks.”8 The recreational use of sleighing did not escape Park City’s residents, especially the youngsters of mining families. In December 1902, “coasting,” with sleighs and bob sleds on city streets, plagued authorities. The Park Record, reporting on a City Council meeting, noted,

The question of coasting on the streets then came up and was gone over pretty thoroughly, and a motion prevailed that a notice be published in The Record notifying all parties that all coasting would be strictly prohibited on any street other than Woodside Avenue. Special attention will be given by the police officers to the cross streets in prohibiting coasting, and those who disregard this notice will be severely dealt with.9

However, in the same issue, a report appeared demonstrating the ingenuity of the youngsters in eluding authority.

The police are trying to get on to the code of signals used by the small boys in warning each other when the officers are about at such times as they want to coast on forbidden streets. They have got so far as to know that when a kid yells “chisel” it means to the boys on the next corner that the police are heading that way. “Shovel” means wait a few minutes, and “pick” that all is well. The police say, however, that they believe the boys are changing the code on them, and freely admit it is a hard combination.10

Note the use of mining terms in the youths’ coding system.

Nevertheless, accidents did occasionally happen, as printed in the Reporter:

Leo Lenzi, the 13 year old son of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Lenzi, while sleigh riding on Woodside avenue Thursday night, was run into by a pair of “bobs” and had his leg badly fractured…Coasting is a splendid sport, but is rather dangerous for little folks.11

The article did mention sleigh riding and bobsled riding as “sports.”

Undoubtedly, early skiing functioned as a means of winter travel in the steep Park City terrain. References remain unclear as to the first use of skies; however, various sources identify their use as a “necessity” during the first decade of the twentieth century.12 Workers, especially those responsible for maintaining telephone service, often utilized homemade skis in journeying from Park City to Brighton in the dead of winter.

One resident, Earl Smith, recalled his childhood in the early 1900s, and how he and some friends utilized barrel staves to construct skis. “They turned up at the ends, and we used a piece of leather and nails on the side of the barrel…We used to ski on the street and on the hill back of the house. We did a lot of falling and a lot of tumbling around.”13

In 1909 Park City received an incredible snow fall. Mountain roads became blocked and trains snowbound. A later account maintained that the Park Record editor “claimed that skiers came down Treasure Hill so fast it made him gasp to watch them!”14 This monumental storm did provide for one of the earliest known contests of “the novel sport.” In mid March 1909, the Reporter advertised a “Snow Shoe Race,” stating that,

The novel entertainment given by the Swede-Finish [sic] Benevolent and Aid Association last Sunday morning proved a successful affair and some 300 people witnessed the sport. There were a number of entries, and the way some of the men handled themselves on skiis (sic) demonstrated that they had been on them before in the “old Country.[“]…

There are many expert skii [sic)]artists in Park City and now that this sport has been commenced another winter should see several of these racing tournaments with prizes offered that would make it worth while competing for.15

Advertising the event began some two weeks prior, with the competition taking place in “Smiths Field,” Deer Valley.

During the late 1910s and into the early 1920s, Park City’s potential for skiing began to capture the imagination of other sports minded enthusiasts. Members of the Wasatch Mountain Club explored the canyons above the city. In March 1922, the Utah Ski Club met at Park City, spending a day of jumping on Treasure Hill.16 The Park Record announced, “Park City’s First Skiing Tournament,” in the 23 February 1923 issue. In somewhat prophetic language, the newspaper informed its readers,

Yesterday was a gala day for winter sports in Park City, and the first of annual events that will result in bringing many hundreds of people to Park City, and advertising our city as a “mecca” for winters sports, that are so attractive in other mountain cities–but none as ideal for such sports as Park City…Ski jumping was the feature, and some pretty work witnessed…17

The article also mentioned Fraser Buck, W. P.Westfield, Glen Wentworth and “Bud” Wright as the “live ones in the winter sports movement…”18

Ski jumping and skiing in Park City from the 1920 onward is chronicled in other publications.19 But a direct link to mining history occurred during the 1964-1965 ski season when the Spiro Tunnel, used to drain the Silver King Consolidated Mine workings, became transformed into an “underground ski life.”20 The “SilverCon,” a competitor to Kearns’ Silver King, drove the tunnel in 1916, under supervision of the mine’s owner, Solon Spiro. The area served by the tunnel ceased operations in about 1937, and the mine closed in 1948.

With the expansion of the ski industry and a Park City building boom in the early 1960s, the Spiro Tunnel figured in plans to provide skiers with a way to the upper areas of Treasure Hill. The Park Record chronicled the event, as follows:

…this train is one of two which will operate as part of the world’s first underground ski lift. The Train, unlike anything a miner has ever seen in the depths of the earth, was starting its 25-minute, three-mile journey into the famous Spiro Tunnel at Park City…

The Tunnel ski lift began its first regular day of operation Saturday and several hundred skiers got their first look at the inside of a “real mine”…

The train rocks and rumbles through the tunnel, then slows slightly as it passed the halfway point—7,000 feet into the tunnel…

Once the train reaches the end of the almost-level tunnel, the passengers begin the “lift” part of the ride.

Passengers leave the train and are loaded on small elevator-type compartments (cages) in the mine’s hoist shaft. After the compartments are loaded, the hoist starts its rapid 1,700 foot ascent to ground level.

Two and a half minutes after entering the “elevators,” passengers step out into the mountain top’s sunshine.21

The ride itself was operated by experienced miners, who maintained the trains, tracks, and timbers.

Thus, the connection between mining and skiing in Park City remains forever entwined. From the days of Thomas Kearns, as miner and entrepreneur, to the Swedish and Finnish miners who undoubtedly plied their mode of snow travel to and from the mines, Park City’s mining background continues to focus as the “historic” roots of this recreational haven.

Endnotes

1. Salt Lake Tribune (Salt Lake City, Utah), 2 November 1899.

2. Ibid., 31 December 1901.

3. Park Record (Park City, Utah), 15 November 1902.

4. Salt Lake Tribune, 18 November 1902.

5. Park Record, 30 January 1897.

6. Ibid., 6 February 1897.

7. Ibid., 13 February 1897.

8. Ibid., 22 November 1902.

9. Ibid., 20 December 1902.

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid., 10 January 1903.

12. George A. Thompson and Fraser Buck, Treasure Mountain Home. A Centennial History of Park City, Utah (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Company, 1968), 215; and “Park City Turns to Skiing,” video production produced by David Hampshire and Larry Warren, 1987.

13. “Skiing Exhibit,” Park City Museum.

14. Thompson and Buck, Treasure Mountain Home,198.

15. Park Record, 20 March 1909.

16. Thompson and Buck, Treasure Mountain Home, 215.

17. Park Record, 23 February 1923.

18. bid.

19. See, David Hampshire, Martha Sonntag Bradley, and Allen Roberts, A History of Summit County. Utah Centennial County History Series (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society and Summit County Commission, 1998), 313–329.

20. Thompson and Buck, Treasure Mountain Home, 254–258.

21. Park Record, 14 January 1965.