Becky Bartholomew

History Blazer, December 1995

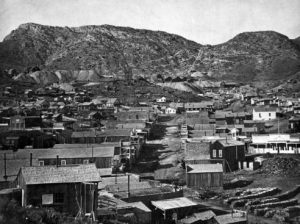

Pioche, Nevada

The rich ores of Pioche, Nevada, were discovered as early 1864, but the camp developed rather slowly at first. About 1870 a Frenchman named F. L. A. Pioche came in and began development in earnest. The camp was named for him. Soon two other men, William Raymond and John Ely, began working the Raymond-Ely section of the camp. Outlaws, gamblers, saloon men, claim jumpers, and bad men and wild women of every kind swarmed in, and Pioche soon became the wildest, bloodiest, most lawless camp in the whole West—rivaling even Tombstone, Arizona. Murders were almost weekly occurrences, and it was a dull week when there were no killings. Most occurred in the saloons and gambling dens. Reportedly, there were 72 killings before there was one natural death.

Pioche was the hungriest camp within the range of southern Utah, and peddlers from Millard, Beaver, Iron, and Washington counties went there. Usually they did well in spite of the risks. The Nevada mining camps were the market places for about all the surplus commodities produced by southern Utah farmers. Taking hay, grain, flour, hams, bacon, poultry, young pigs, lumber, shingles, mine timbers, butter, cheese, and many other things to supply Pioche, Bullionville, and other camps, peddlers were on the road almost constantly. Utah producers appreciated having such a good cash market for their commodities. Loads of lumber, shingles, and mine timbers were bought outright by mine companies and lumber dealers. Most other commodities were sold door-to-door. Peddlers who were honest in their dealings and carried good grade merchandise had little difficulty in selling out their loads.

Established stores in Pioche suffered a loss of business to the produce peddlers. The merchants thought they had a right to a commission on all goods sold by outsiders in their territory. The commission idea was not accepted by the Utah peddlers, but they made a compromise proposal. They proposed to sell their loads on a wholesale basis to the stores. If they could unload in one place it would save a day or two of time on each trip and the unpleasant task of house-to-house canvassing. For a time, as long as dealer and peddler dealt fairly with each other, the system benefited both.

But a time came when the Pioche stores began to squeeze the peddlers. The produce, of course, was not of uniform quality nor had it ever been, and this was used to beat down prices. Also, the dealers became “choosey” and instead of buying out the entire load as they had agreed, they would take only what they wanted. Some Utahns tried to beat the dealers’ “racket” by returning to door-to-door peddling, but it proved hazardous. The unscrupulous dealers set up a “goon” squad, and somewhere out in the woods on his way home the peddler would turn the point of a hill and find himself looking down the barrel of a gun in the hands of a highway robber. Under such circumstances it was healthier to give up his money than fight for it. So the Utah farmers were forced to freight their produce to the mining camps and take the best prices the dealers would pay. Prices dropped to two cents a pound for grain—about one-half or one-third of what they should have been.

Brigham Young spent the winter of 1873–74 in St. George and learned firsthand about these conditions. Times were hard, for the Panic of the 1870s was at its worst in Utah. There had also been heavy crop losses from frosts and insect pests, and the people were very discouraged. Young saw that in the final analysis the mining camps were almost wholly dependent upon the Mormon settlements for a large part of their necessities. There were no other feasible suppliers. Young said, “This is a two-edged sword the mining camps are swinging against us. They are as dependent upon us as we are upon them. We will make the sword cut the other way until they recognize that their game can be played by our side too.” He organized the southern settlements into United Orders and told the people to stop hauling their produce to the mining camps for awhile and see what happened. Then he appointed an agent in every town to deal with the camps when they came to Utah to buy, as he knew they must do sooner or later. He also suggested the prices they should ask.

When the Mormon peddlers stayed home, conditions soon became desperate in Pioche, with no hay, grain, dairy, or poultry products to be had. The dealers were forced to come to Utah and contract at Mormon prices for the produce they must have. They were glad to contract on a delivered basis at four to six cents a pound for the grain they had extorted from the peddlers at two cents a pound. The grain was paid for, freight included, in advance. The Mormon freighters delivered the goods, and, since they carried no money, the holdups stopped.

Source: William R. Palmer, “Early-day Trading with the Nevada Mining Camps,” Utah Historical Quarterly 26 (1958).