Jeffrey D. Nichols

History Blazer, April 1995

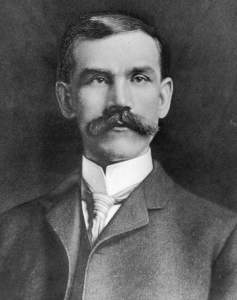

Reed Smoot

During the 1930s the economies of all of the industrialized nations suffered dramatic declines in production, trade, and employment levels. Already weakened by the human and economic toll of World War I, war debt repayment, and trade imbalances with the United States, foreign nations were confronted in 1930 with the highest tariff barriers in U. S. history. The chief architect of the American protectionist legislation was Utah’s Senator Reed Smoot.

Tariffs, or duties on imported goods, have long been a divisive and controversial issue in American politics. Supporters of high tariffs—generally Federalists, then Whigs, and later Republicans—argued that they protected American business and industry from foreign competition. Opponents, usually Democrats and those who favored cheap imports, called for lower tariffs. Alexander Hamilton had recommended tariffs high enough to protect infant American industries in 1791, an idea rejected at the time by a Congress more interested in an agricultural than a manufacturing economy. Tariffs were a central part of Henry Clay’s early 19th-century “American System” and were expected to simultaneously encourage domestic manufacture and provide revenue for internal improvements. The Tariff of 1832 nearly led to bloodshed between the federal government and the state of South Carolina. At a time when slavery and sectionalism dominated politics, the tariff was one of the few other national issues.

When Smoot entered Congress in 1903 the nation was operating under the Dingley Tariff of 1897, at the time the highest in the nation’s history. Smoot, appointed to the Senate Finance Committee in 1908, quickly became an expert on tariff issues, mastering the complex and arcane tariff schedules on a variety of goods and becoming a firm and unyielding advocate of high duties. The Utahn was particularly concerned throughout his political career with the tariffs on sugar and wool, two major Utah products that competed with imports. While Republicans held power they were able to keep the tariff relatively high. When Democrats took the presidency and both houses of Congress in 1912, tariffs were sharply reduced.

The return of Republicans to national power in 1920 led to a resumption of protectionist legislation. By now a power in the Senate, Smoot was a close economic adviser to Presidents Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover. In 1923 the Fordney-McCumber Tariff raised rates again, including those on Cuban sugar, a direct competitor with Utah’s beet sugar industry. With Smoot’s ascension to the chairmanship of the Finance Committee even higher rates were assured. In 1930 President Hoover signed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff which boosted average duties on imports to 53 percent, the highest in American history. While Smoot saw this legislation as the culmination of his protectionist career, most economists then and since have assailed the tariff’s disastrous effect on world trade at a time when the domestic economy of the U. S. was already suffering. The higher rates, about one-third greater than previous duties, made it more difficult for foreign nations to purchase American goods and pay off their war debts. In retaliation, some twenty-five nations raised their duties, making American goods more expensive. By the time the Democrats took power in 1932 and lowered the tariffs under the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act in 1934 the world economy was in a tailspin.

Smoot never fully acknowledged the unintended consequences of his legislation. In fact, he argued in the depths of the depression that the rate might not be high enough. The 1930 tariff was “the Great Protectionist’s” proudest achievement.

Sources: James B. Allen, “The Great Protectionist: Sen. Reed Smoot of Utah,” Utah Historical Quarterly 45 (1977); Mary Beth Norton et al., A People and a Nation (Boston, 1990).