Becky Bartholomew

History Blazer, January 1996

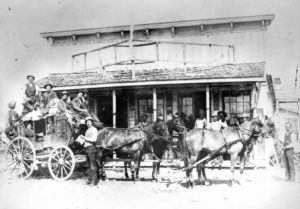

Stagecoach scene, photo taken by the L. H. Jourd Commercial Photo Shop

In the mid-1800s Ben Holladay was famous as the colorful owner of the largest stagecoach line in the world. He had six homes, a stylish wife of American Revolution lineage who helped him collect art and books, daughters married to European counts, and an international playboy son. The other son helped manage his steamship fleet and Nevada silver mines.

Holladay was well liked. Darkly handsome, he enjoyed a good joke and did not mind moderate swearing, but he insisted that his employees be respectful. He employed several thousand drivers, but several times a year he would ride the line coast to coast himself to prove that his stages were punctual and could still beat competitors from Atlantic to Pacific.

Ben Holladay’s stagecoach at Kimball Station, 1867. Courtesy: Standard Optical (from the John F. Bennett Collection). Used in U.H.Q. Spring 1963. Digital Image © 2014 Utah State Historical Society.

Probably the key to Holladay’s success was his organizing drive. It was said that nothing was too big for him to undertake. The Army and other clients knew a contract with him meant on-time delivery. Yet he loved to gamble, at times playing his way out of a poker game or a financial deal through sheer bluff. The precariousness of the freighting business appealed to him as much as its outlandish profits.

But what was little known was that Holladay’s first real successes came through trading with the Mormons, with whom he maintained close business ties throughout his career.

This connection began while he was 18-year-old aide-de-camp to Missouri militia commander Alexander Doniphan, who was sent to disarm a supposed Mormon uprising. Arriving in the Mormon settlements, Doniphan discovered the problem had been misrepresented and refused to fire on the Mormons. His level-headedness probably influenced young Holladay.

When the California gold rush began, the Mormons had already relocated to the Great Basin. Holladay, always the independent thinker, could see there was surer fortune to be gained from freighting than gold digging. That June he arrived in Salt Lake City bearing letters of recommendation from Doniphan and others. He had hauled fifty wagons filled with $70,000 in Mexican War surplus from St. Louis, but he needed help getting them over the mountains.

For the next several years Holladay and his partner Theodore Warner joined early Salt Lake merchants Vasquez, Livingston & Kinkead, John and Enoch Reese, Thomas S. Williams, and Elijah Thomas in providing the isolated territory with badly needed eastern products. Then Holladay took his surplus oxen to California where, by holing up in the foothills until San Francisco buyers met his price, he got $500 per head–having paid $6.

The next year Holladay arrived in Utah with $150,000 in goods. His enormous profits came largely from selling war surplus for private goods wholesaled in St. Louis at two to four times the prices commanded in Utah.

Holladay & Warner differed in policies from some gentile merchant houses. They accepted goods when cash was not available, and they did not discount the coin Mormons minted for a time using inferior amounts of gold. After entering the stagecoach business, Holladay assisted Mormons with loans and trading considerations–much of the line’s grain came from Utah farms.

The relationship was mutually beneficial. Many of Holladay’s superintendents, drivers, and riders were Mormons. And in 1864-65, when his line lost $305,000 in the Indian Wars, President Lincoln asked Brigham Young to raise a 90-day cavalry to protect the stages and telegraph. Young responded largely because of Holladay.

By 1866 Holladay’s wife had died and he was tired of the business. He sold the coach line to Wells, Fargo & Company and retired to Portland, Oregon, where he started a hotel, saw mill, and second family.

But in the 1870s he was tempted by a new project. Characteristically, he saw it not just as a railroad line connecting Oregon’s Willamette Valley to the transcontinental railroad terminus in California but as a colonizing effort. Holladay obtained land grants from Oregon state and, using foreign capital, sent his ships to Europe to recruit immigrants to homestead the grants.

In 1873 a panic shook the eastern U.S. and European financial markets. Holladay’s debts were called in. When the dust settled, he was bankrupt. He sold his remaining assets and sued the federal government for losses accrued while carrying the U.S. mails. When in 1877 he was offered $100,000, he refused it. Holladay died in 1887 at age 68 in what his biographers like to call “relative obscurity.”

Sources: J. V. Frederick, Ben Holladay, The Stagecoach King (Glendale, Calif., 1940); Journal History, LDS Church Archives, Salt Lake City, entries for 1849-53; Ellis Lucia, The Saga of Ben Holladay, Giant of the Old West (New York, 1959).